Scientists at Harvard University and elsewhere have used ancient DNA recovered from fossil bones on New Zealand’s South Island to identify the tiny bushmower.Anomalopteryx didiformisIt is one of nine species of flightless birds that once roamed the forested islands of New Zealand.

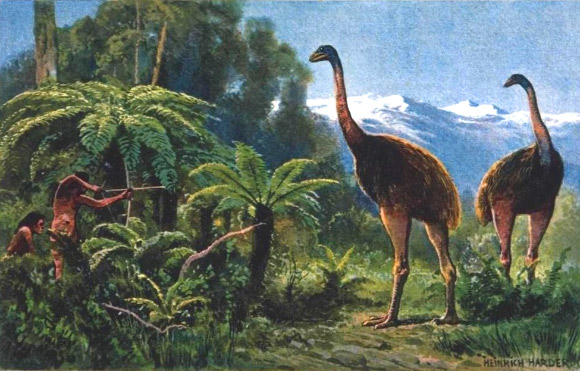

Moas fed on trees and shrubs in the forest understory. Image by Heinrich Harder.

There are currently nine recognized species of extinct New Zealand moas, which belong to the infraclass Aves. PaleognathomorphaThese include flightless ratites (ostriches, emus, cassowaries, kiwis, rheas, moas and elephant birds) and flying shorebirds and skylarks.

The extinction of all moa species is thought to have occurred shortly after Polynesian migration to New Zealand in the 13th century, and is the result of direct human exploitation combined with anthropogenic land-use change and impacts associated with invasive species.

“New Zealand’s extinct moa is our Taonga “It’s a species that has fascinated generations of New Zealand children,” said Dr Nick Lawrence, a palaeontologist at the University of Otago who was not involved in the study.

“Since the advent of ancient DNA, we’ve learned a lot more about the nine moa species that call Aotearoa home, but there are still many questions that remain unanswered.”

“Having the nuclear genome of the male little bush moa is the first step in exploring more deeply what makes moas so special. Even though it’s still in draft form, it’s about 85% complete.”

In the new study, Harvard researcher Scott Edwards and his colleagues assembled the complete mitochondrial and nuclear genomes of a male moa by sequencing ancient DNA and comparing it with the high-quality genome of the closely related emu.

They first calculated that the size of the moa nuclear genome was approximately 1.07 to 1.12 billion bases.

By analyzing the genetic diversity of the mitochondrial genome, the researchers estimated the bushmore’s long-term population to be approximately 237,000 individuals.

“Reconstructing the genome of a species like the tiny bushmore is difficult because there is only so much degraded ancient DNA to recover,” said Dr Gillian Gibb, a researcher at Massey University who was not involved in the study.

“In the case of moas, an additional challenge exists because the closest extant species with high-quality genomes to compare with diverged about 70 million years ago.”

“Despite these challenges, we have been able to recover a large portion of the genome, providing insight into moa evolution.”

The authors also investigated genes involved in the moa’s sensory biology and concluded that the bird probably has an extensive sense of smell and ultraviolet (UV) receptors in its eyes.

“This new study uses the genome to estimate the little bushmouse population at around 240,000 individuals, a number that is probably too high and the authors acknowledge it is a rough estimate,” Dr Lawrence said.

“Ecological estimates of moa are Motu “The (country) has a bird population of between 2 and 10 birds per square kilometre, with a total population of between 500,000 and 2.5 million birds.”

“The genome also shows that the little bush moa had a complex olfactory repertoire, which is consistent with what is seen in the moa skull.”

“Moas could also see in the ultraviolet spectrum, which may have helped them to find food, such as brightly colored truffle-like fungi, that they may have dispersed.”

“Moas, like other birds, are sensitive to bitter foods.”

“Moas are the only birds that have completely lost their wings,” added Prof Paul Schofield from the Canterbury Museum, who was not involved in the study.

“In this new paper, we also take a closer look at the big mystery of how this happened, concluding that it is not due to the loss of genes responsible for wing development, as previously suggested.”

“The paper also found that despite having an abnormal arrangement of the olfactory cortex in the brain, moas had normal avian olfactory abilities.”

of study Published in the journal Scientific advances.

_____

Scott V. Edwards others2024. Nuclear genome assembly of the extinct flightless bird, Little Bushmoore. Scientific advances 10(21); doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adj6823

Source: www.sci.news