ITonga was plunged into darkness in the aftermath of a massive volcanic eruption in the early days of 2022. The undersea eruption, 1,000 times more powerful than the Hiroshima bomb, sent tsunamis into Tonga’s neighbouring islands and covered the islands’ white coral sand in ash.

The force of the eruption of the Hunga Tonga Hunga Ha’apai volcano cut off internet connections to Tonga, cutting off communications at the very moment the crisis began.

The scale of the disruption was clear when the undersea cables that carry the country’s internet were restored weeks later. The loss of connectivity hampered restoration efforts and dealt a devastating blow to businesses and local finances that rely on remittances from overseas.

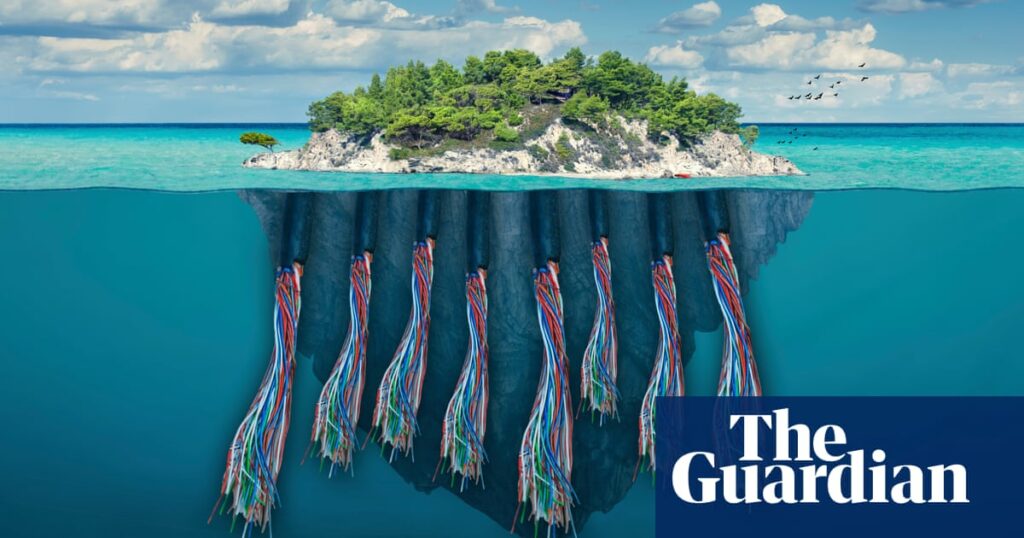

The disaster has exposed extreme vulnerabilities in the infrastructure that underpins how the Internet works.

Nicole Starosielski, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley and author of “The Undersea Network,” says modern life is inseparable from the running internet.

In that sense, it’s a lot like drinking water: a utility that underpins our very existence, and like water, few people understand what it takes to get it from distant reservoirs to our kitchen taps.

Modern consumers have come to imagine the internet as something invisible floating in the atmosphere, an invisible “cloud” that rains data down on our heads. Many believe everything is wireless because our devices aren’t connected by cables, but the reality is far more unusual, Starosielski says.

An undersea internet cable laid on the ocean floor. Photo: Mint Images/Getty Images/Mint Images RF

Nearly all internet traffic — Zoom calls, streaming movies, emails, social media feeds — reaches us through high-speed fibre optics laid beneath the ocean. These are the veins of the modern world, stretching for around 1.5 million kilometres beneath the surface of the ocean, connecting countries through physical cables that conduct the internet.

Speaking on WhatsApp, Starosielski explains that the data transmitting her voice is sent from her phone to a nearby cell tower. “That’s basically the only radio hop in the entire system,” she says.

It travels underground at the speed of light from a mobile phone tower via fibre optic cable on land, then to a cable landing station (usually near water), then down to the ocean floor and finally to the cable landing station in Australia, where The Guardian spoke to Starosielski.

“Our voices are literally at the bottom of the ocean,” she says.

Spies, Sabotage, and Sharks

The fact that data powering financial, government and some military communications travels through cables little thicker than a hose and barely protected by the ocean water above it has become a source of concern for lawmakers around the world in recent years.

In 2017, NATO officials reported that Russian submarines were stepping up surveillance of internet cables in the North Atlantic, and in 2018 the Trump administration imposed sanctions on Russian companies that allegedly provided “underwater capabilities” to Moscow for the purpose of monitoring undersea networks.

At the time, Jim Langevin, a member of the House Armed Services Committee, said a Russian attack on the undersea cables would cause “significant harm to our economy and daily life.”

Workers install the 2Africa submarine cable on the beach in Amanzimtoti, South Africa, in 2023. Photo: Logan Ward/Reuters

Targeting internet cables has long been a weapon in Russia’s hybrid warfare arsenal: When Russia annexed Crimea in 2014, Moscow cut off the main cable connection to the peninsula, seizing control of the internet infrastructure and allowing the Kremlin to spread disinformation.

Global conflicts have also proven to wreak unexpected havoc on internet cable systems: In February, Iran-backed Houthi militants attacked a cargo ship in the Red Sea. The sinking of the Rubimaa likely cut three undersea cables in the region, disrupting much of the internet traffic between Asia and Europe.

The United States and its allies have expressed serious concerns that adversaries could eavesdrop on undersea cables to obtain “personal information, data, and communications.” A 2022 Congressional report highlighted the growing likelihood that Russia or China could gain access to undersea cable systems.

It’s an espionage technique the US knows all too well: in 2013, The Guardian revealed how Britain’s Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) had hacked into internet cable networks to access vast troves of communications between innocent people and suspected targets. This information was then passed on to the NSA.

Documents released by whistleblower Edward Snowden also show that undersea cables connecting Australia and New Zealand to the US were tapped, giving the NSA access to internet data in Australia and New Zealand.

Despite the numerous dangers and loud warnings from Western governments, there have been few calls for more to be done to secure cable networks, and many believe the threat is exaggerated.

The 2022 EU report said there were “no published and verified reports suggesting a deliberate attack on cable networks by any actor, including Russia, China or non-state groups.”

“Perhaps this suggests that the threat scenarios being discussed may be exaggerated.”

One expert speaking to the Guardian offered a more blunt assessment, describing the threat of sabotage as “nonsense”.

TeleGeography map of undersea internet cables connecting the US, UK and Europe. Photo: TeleGeography/https://www.submarinecablemap.com/

The data bears this out, showing that sharks, anchors and fishing pose a bigger threat to the global Internet infrastructure than Russian espionage. A US report on the issue said the main threat to networks is “accidental human-involved accidents.” On average, a cable is cut “every three days.”

“In 2017, a vessel accidentally cut an undersea communications cable off the coast of Somalia, causing a three-week internet outage and costing the country $10 million per day,” the report said.

An Unequal Internet

But for many experts, the biggest risk to the internet isn’t sabotage, espionage or even rogue anchors, but the uneven spread of the globe-spanning cable infrastructure that ties together the world’s digital networks.

“There aren’t cables everywhere,” Starosielski said. “The North Atlantic has a high concentration of cables connecting the U.S. and Europe, but the South Atlantic doesn’t have as many.”

“So you’re seeing diversity in terms of some parts of the world being more connected and having multiple routes in case of a disconnection.”

As of 2023, there are more than 500 communication cables on the ocean floor. Map of the world’s submarine cable networks These are found to be mainly concentrated in economic and population centres.

Map of undersea internet cables in the South Pacific.

The uneven distribution of cables is most pronounced in the Pacific, where a territory like Guam, with a population of just 170,000 and home to a U.S. naval base, has more than 10 internet cables connecting the island, compared with seven in New Zealand and just one in Tonga, both with a population of more than 5 million.

The aftermath of the 2022 Tonga eruption spurred governments around the world to act, commissioning reports on the vulnerabilities of existing undersea cable networks while technology companies worked to harden networks to prevent a similar event from happening again.

Last month, Tonga’s internet went down again.

Damage to undersea internet cables connecting the island’s networks caused power outages across much of the country and disruption to local businesses.

For now, economic fundamentals favor laying cables to Western countries and emerging markets where digital demand is surging. Despite warnings of sabotage and accidental damage, without market imperatives to build more resilient networks, there is a real risk that places like Tonga will continue to be cut off, threatening the very promise of digital fairness that the internet is based on, experts say.

Source: www.theguardian.com