Methane plume at least 4.8 kilometers long pours into the atmosphere south of Tehran, Iran

NASA/JPL-California Institute of Technology

The world now has more ways than ever to discover invisible methane emissions, which are so far responsible for a third of global warming. But methane “super emitters” take little action even when warned that they are leaking large amounts of the powerful greenhouse gas, according to a report released at the COP29 climate summit.

“We’re not seeing the transparency and urgency that we need,” he says. Manfredi Caltagirone director of the United Nations Environment Programme’s International Methane Emissions Observatory, recently launched a system that uses satellite data to alert methane emitters of leaks.

Methane is the second most important greenhouse gas to tackle after carbon dioxide, and more countries are pledging to reduce methane emissions to avoid short-term warming. At last year’s COP28 climate summit, many of the world’s largest oil and gas companies also pledged to “elimate” methane emissions from their operations.

Today, more and more satellites are beginning to detect methane leaks from the biggest sources of methane emissions, such as oil and gas infrastructure, coal mines, landfills, and agriculture. That data is critical to holding emitters accountable, he says. mark brownstein at the Environmental Defense Fund, an environmental advocacy group that recently launched its own methane sensing satellite. “But data alone won’t solve the problem,” he says.

The first year of the UN’s Methane Alert System shows a huge gap between data and action. Over the past year, this program has 1225 alerts issued When we saw plumes of methane from oil and gas infrastructure large enough to be detected from space, we reported them to governments and companies. To date, emitters have taken steps to control these leaks only 15 times, reporting a response rate of about 1 percent.

There are many possible reasons for this, Caltagirone says. Although emissions from oil and gas infrastructure are widely considered to be the easiest to deal with, emitters may lack the technical or financial resources and some methane sources may be difficult to shut down. there is. “It’s plumbing. It’s not rocket science,” he says.

Another explanation may be that emitters are not yet accustomed to the new alarm system. However, other methane monitoring devices have reported similar lack of response. “Our success rate is not that good,” he says Jean-François Gauthier GHGSat is a Canadian company that has been issuing similar satellite alerts for many years. “About 2 or 3 percent.”

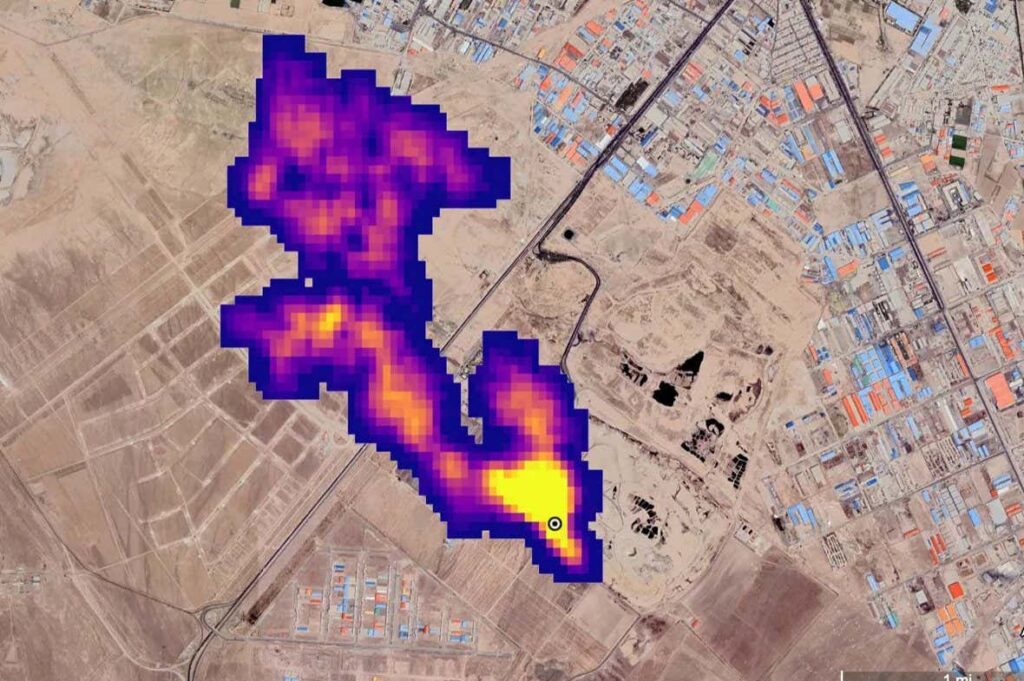

Methane super emitter plume detected in 2021

ESA/SRON

There are also some success stories. For example, the United Nations issued several warnings this year to the Algerian government about a source of methane that has been leaking continuously since at least 1999, and whose global warming impact is equivalent to driving 500,000 cars a year. It is said to be equivalent. By October, satellite data showed it had disappeared.

But the big picture shows that monitoring is not yet leading to emissions reductions. “Simply showing a plume of methane is not enough to take action,” he says. rob jackson at Stanford University in California. The central problem, he sees, is that satellites rarely reveal who owns leaky pipelines or methane-emitting wells, making accountability difficult.

Methane is a major topic of discussion at the COP29 conference currently being held in Baku, Azerbaijan. a summit At a meeting on non-CO2 greenhouse gases convened by the United States and China this week, each country announced several measures on methane emissions. That includes a U.S. fee on methane for oil and gas emitters, a rule many expect the incoming Trump administration to roll back.

topic:

Source: www.newscientist.com