“Rachel, I have some unfortunate news,” the text read. “They are planning to dismantle the loom tomorrow.”

Rachel Halton still doesn’t know who made the decision in October 2022 to eliminate the $160,000 jacquard loom, which had been the foundation of RMIT’s renowned textile and textile design course for two decades.

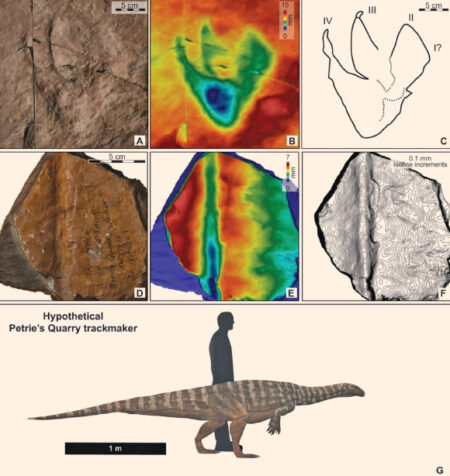

Standing at 3 meters tall and weighing over half a tonne, the loom was an intricate machine made of polished wood, steel, compressed air, and mechatronics. It served as both a grand tribute to the textile industry’s golden age and a modern tool for weaving intricate fabrics from strands of thread. Halton couldn’t bear the thought of it ending up in a landfill.

The Jacquard Loom uses punch cards—an early form of coding—to guide the lifting and dropping of threads.

Photo: Stuart Walmsley/Guardian

“It was my day off, and I jumped out of bed and rushed over,” recalls Halton.

The loom was unique in the Southern Hemisphere and one of only a few globally. Halton acquired it for the university’s Brunswick campus in the early 2000s soon after she began teaching there. It “expanded artistic possibilities,” she states. Students enrolled specifically to work with it, and international artists visited to weave on it. It became integral to Halton’s creative process.

Upon her arrival on campus that October morning, she was determined to “rescue it from the brink.”

“He severed it right in front of me,” Halton recounts. “It felt like I was pulling the plug on a family member’s life support.”

Many shared her sentiment, prompting a grassroots effort to save the loom as news spread about its impending removal. A passionate collective of weavers, educators, students, and alumni rallied to find it a more suitable home, all while carefully disassembling it for transport to a compassionate technician’s workshop, eventually settling on a former student’s living space.

Textile artist Daisy Watt, part of that collective, describes the event as a “telling snapshot of the challenges” facing higher education in arts and crafts.

Warp and Weft

The loom’s cumbersome name underscores its significance. Traditional jacquard looms utilize punch cards (rows of holes in cardboard slips, the earliest form of coding) to control the lifting of vertical (warp) threads and weave fabric through thread manipulation. The Arm AG CH-3507 loom can be operated manually or via computer, providing total control over every thread and opening up limitless design avenues.

Watt collaborates with technician Tony De Groot to restore the loom.

Photo: Stuart Walmsley/Guardian

Watt has a “deep connection” to the loom. Not only did she invest countless hours during her time at RMIT, but she also housed it for months post-rescue. Self-taught in coding, she is now updating its electronics. Given its roots in Jacquard punch card technology, it feels as though the loom is intertwined with the **fundamentals of modern computing.**

“We often think of crafting as separate from technology, yet this embodies the beautiful chaos of that intersection,” Watt explains. “Effective crafting technology revolves around creating beauty.”

Instructor Lucy Adam notes that when the loom was acquired, RMIT offered textile design as part of its arts diploma.

After the newsletter promotion

In 2008, RMIT shifted from offering a diploma to a Certificate IV training package, part of a wider and controversial national restructuring of vocational education. This approach omitted traditional curricula in favor of job-focused “competency units” directed by industry, all under stringent regulation.

Government officials defended these reforms as necessary for streamlining qualifications and eliminating underperforming training providers. However, educators and union representatives warned that this would dilute educational quality, resulting in a systemic decline in skill development which labor theorist Harry Braverman described as a shift from “conscious skilled labor” to rudimentary tasks.

Testimonies from RMIT’s textile design faculty indicate this was indeed the outcome despite their best efforts.

De Groot inspects educational materials recovered from the loom.

Photo: Stuart Walmsley/Guardian

The program has become “very dry and at the lowest common denominator,” according to Adam. Resources have been cut back significantly, and student interaction time has halved. Despite the loom’s educational potential, there was insufficient time to teach students how to operate it adequately. Halton endeavored to integrate it into student projects as much as possible, personally overseeing its setup, disassembly, and maintenance.

In her Master’s thesis, Adam scrutinized the effects of these changes on vocational education and noted that competency checklists missed the essence of trade disciplines like textile design, ceramics, cooking, metalworking, woodworking, and other fields that marry technical skills with artistic expression.

“Unless you are an exceptionally skilled educator capable of circumventing the banality, you’re relegated to an archaic teaching model,” she argues.

Artist and educator John Brooks echoes the concerns about the restrictive course structure, highlighting that even basic tasks like starting or shutting down a computer are now considered part of the evaluation requirements. “With so much focus on compliance, we compromise the fundamental skills we aim to teach,” he laments.

Adam remembers a student lamenting their training package, saying it felt like “filling out a visa application repeatedly.” “It truly saddened me,” she reflects. “Where does real learning take place? Where can you learn it?”

The loom’s new location in Ballarat.

Photo: Stuart Walmsley/Guardian

This trend isn’t confined to TAFE. Ella*, a third-year student from the University of Tasmania, shares with Guardian Australia that advanced 3D media courses, particularly in her areas of focus—furniture, sculpture, or time-based media—cease after the first year. There are also no offerings in art history.

“It significantly affects students’ understanding of contemporary art,” Ella asserts. Her instructor is striving to “revitalize” the course.

Professor Lisa Fletcher, representing the Faculty of Arts at the University of Tasmania, emphasizes the institution’s commitment to arts education, stating they aim to equip students with “strong and sustainable skills,” while actively seeking feedback as they regularly evaluate their art degrees.

Crafting the Future

The loom is currently housed in an incubator space in Ballarat, where rescue organizations can operate for minimal fees. The city is dedicated to preserving rare and endangered craft techniques. Certain crafts have nearly disappeared; for instance, stained glass work, once close to being extinct in Australia, has seen a revival thanks to a handful of artists who successfully reintroduced it into the TAFE system and launched a course in Melbourne’s polytechnics. However, such revivals are rare.

Watt and fellow weavers aspire for looms to be accessible once more, allowing others to learn, teach, and create. As Brooks puts it, the less prevalent these skills become, the fewer opportunities there will be to acquire them. “We’re in danger of losing them altogether.”

An RMIT spokesperson mentioned that the university had to remove the looms as part of an upgrade to ensure students had access to “reliable and modern equipment” that prepares them for the workforce. Presently, the space previously occupied by the looms is dedicated to military-funded textile initiatives, requiring security clearance for entry. Last year, RMIT stopped accepting enrollments for the Certificate IV in Textile Design after state government funding for the course was withdrawn.

Yet, there is a glimmer of hope. Adam remains determined; she recently proposed a new diploma that has been approved. Despite the growing constraints, she isn’t alone in her endeavors at the university. As of this writing, the institution is set to acquire new equipment—a modest yet promising $100,000 computer-controlled Jacquard loom.

*Name changed

Source: www.theguardian.com