koto_feja/Getty Images

koto_feja/Getty Images

Traditionally, we envision particles as tangible objects—tiny, point-like entities with specific properties like position and velocity. In reality, however, particles are energetic fluctuations within an underlying field that fills the universe, and they cannot be directly observed. This concept can be quite perplexing.

This article is part of our special focus on concepts, examining how experts interpret some of the most astonishing ideas in science. Click here for more information.

Furthermore, there exists a layer of complexity due to quasiparticles, which arise from intricate interactions among the “fundamental” particles found in solids, liquids, and plasma. These quasiparticles possess fascinating properties of proximity, suggesting the potential for exotic new materials and techniques, challenging our established notions of particles.

“When discussing what particles are, the topic can become quite convoluted,” states Douglas Natelson from Rice University in Houston, Texas. He describes quasiparticles as “excitations in a material that exhibit many characteristics associated with particles.” They can have relatively well-defined positions and velocities and can carry charge and energy. So why aren’t they considered actual particles?

The answer lies in their existence. Natelson likens this to fans performing “waves” in a stadium. “We can observe the waves and think, ‘Look! There’s a wave, it’s of a certain size, moving at a specific speed.’ But those waves are essentially a collective phenomenon, resulting from the actions of all the fans present.”

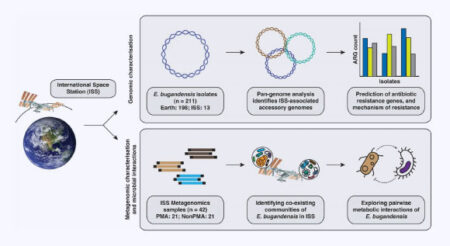

To create a quasiparticle, physicists often manipulate materials like metal substrates subjecting them to extreme temperatures, pressures, or magnetic fields. Subsequently, they study the collective behavior of the intrinsic particles.

One intriguing phenomenon recognized in the 1940s involved a “hole,” which describes a lack of negative electrons that should normally be present. By analyzing these holes as if they were independent entities, researchers were able to develop semiconductors that power modern laptops and smartphones.

“Essentially, modern electronics hinge on both electrons and holes,” remarks Leon Balents from the University of California, Santa Barbara. “We continuously utilize these quasiparticles.”

Over the years, we have uncovered an entire spectrum of exotic quasiparticles. Magnons emerge from spin waves, a fundamental quantum property related to magnetism. Cooper pairs, present at low temperatures, can transmit charge without resistance in superconductors. The list expands, continually growing as physicists predict and observe peculiar new types with strange names, such as pi tons, fractures, and even wrinkles.

Among the more thrilling discoveries is the non-Abelian anyon. Unlike typical particles, these quasiparticles possess the ability to retain memory of how they were altered.

The practicality of these quasiparticles remains uncertain, according to Balents. Nonetheless, major companies like Microsoft have heavily invested in research involving quasiparticles.

The ongoing investigation raises fundamental questions about particle nature itself. If quasiparticles exhibit particle-like characteristics, one must consider whether the “fundamental” particles (e.g., electrons, photons, quarks) might emerge from a more profound underlying framework.

“Are what we classify as fundamental particles truly elementary, or could they be quasiparticles arising from more basic fundamental theories?” ponders Natelson. “An eternally looming question.”

Explore more articles in this series via the links below:

Source: www.newscientist.com