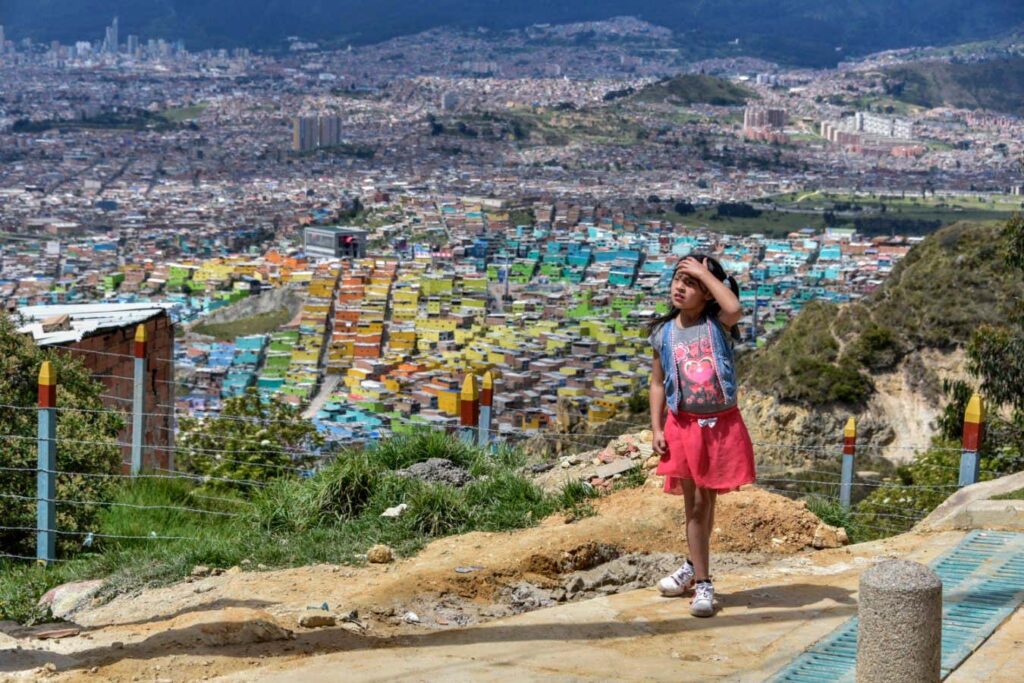

Research reveals obesity rates among children in Colombia’s hilly capital, Bogotá

Guillermo Legaria/Getty Images

A study involving over 4 million children in Colombia suggests that living at high altitudes may help in preventing obesity.

This outcome is consistent with existing research. Higher altitudes are thought to reduce obesity, potentially due to increased energy expenditure at lower oxygen levels. Most studies, however, have focused primarily on adults.

To explore the effect on children, Fernando Lizcano Rosada from Lhasavanna University in Chia, Colombia, along with his team analyzed data concerning 4.16 million children from municipalities up to age 5, sourced from the Colombian Institute of Family Welfare.

The participants were categorized into four groups based on the altitudes where they resided.

In two low-altitude areas, about 80 out of every 10,000 children were classified as obese. In contrast, at altitudes of 3,000 meters or higher since 2001, this rate dropped to 40 per 10,000.

However, at elevations above 3,000 meters, the prevalence rose again, reaching 86 out of 10,000. The researchers caution that this might be a statistical anomaly since it is based on data from only seven municipalities and 11,498 individuals, substantially fewer than the data for the other altitude groups.

“That’s a valid observation,” states David Stencel from Loughborough University, UK. He notes that a dose-response relationship would have strengthened the findings.

Stencel also underscores that the study is observational, meaning it does not definitively prove that high altitudes reduce obesity risk. “The research takes into account various confounding factors,” he explains, including measures of poverty. Yet, he adds, “we cannot account for everything.”

Nevertheless, he sees this research as a promising commencement. “It establishes a relationship that calls for more tailored studies to verify the hypothesis independently.”

Lizcano Rosada posits that metabolism may be heightened at higher altitudes, leading to increased energy expenditure.

This claim is plausible, Stencel agrees. “Some studies indicate that resting metabolic rates may be elevated at high altitudes,” he notes. For instance, a 1984 study found that climbers tended to lose more weight at high altitudes partly because fat from food was burned or expelled before being stored as tissue.

More recent studies suggest that lower oxygen levels may lead to accelerated metabolism and increased levels of leptin, the hormone related to satiety, while levels of ghrelin, often associated with hunger, are reduced.

If it is indeed true that high altitude diminishes obesity risk, Stencel notes that the practical application of this knowledge in combating obesity remains ambiguous. Nonetheless, Lizcano Rosada asserts that personalized advice could be beneficial, acknowledging that diverse environmental factors contribute to obesity across various locales.

topic:

Source: www.newscientist.com