Ludovic Slimak contributed to revealing the remains of Thorin, a Neanderthal

Laure Metz

The Last Neanderthal

Ludovic Slimak (translated by Andrew Brown) (Polity Press (UK, September 26, US, November 24))

Chance findings of Neanderthal skeletons, hardened soot, and small arrowhead tools beneath leaves at the French Grotte Mandrin have reshaped not only our perception of Neanderthals but also our understanding of early Homo sapiens migrations into Europe.

More intriguingly, this cave has unveiled insights about the initial interactions between the two groups and the reasons behind the success of one species and the extinction of another. This pivotal issue is explored in The Last Neanderthal: Understanding How Humans Die, a new work by Ludovic Slimak, a paleontologist from the University of Toulouse who spearheaded the excavations at Grotte Mandrin.

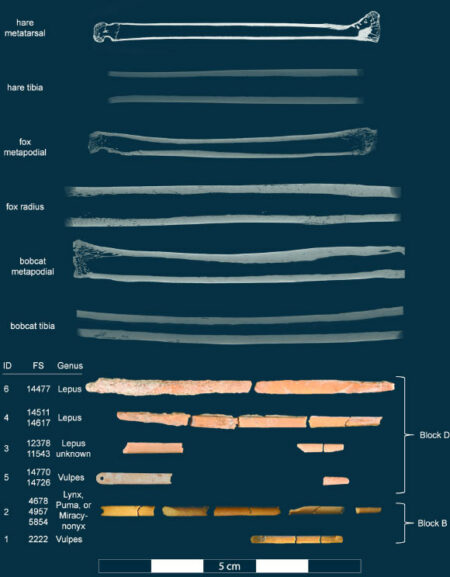

The narrative focuses on Thorin, a Neanderthal fossil unearthed in 2015 at the cave’s entrance, which revealed five teeth during the excavation. The delicate recovery of this singular discovery required painstaking care, extracting each grain of sand with tweezers over seven years to uncover fragments of his skull and hand.

This investigation led to a riveting quest that spanned years, employing various dating methods that initially yielded starkly conflicting timelines for Thorin’s existence. Ultimately, it was determined that the fossils date between 42,000 and 50,000 years ago. The last known Neanderthal population went extinct around 40,000 years ago . Remarkably, Thorin’s genome was sequenced, revealing a previously unknown lineage that diverged from the primary Neanderthal population more than 50,000 years ago and later experienced extreme isolation.

The Last Neanderthal is a deeply introspective and philosophical work, evoking a vivid sense of what it would have meant to explore Thorin’s existence and the myriad groups that inhabited the cave over millennia. Slimak notes that the unique scent of Grotte Mandrin originates from ancient fire soot preserved within the calcite layers of its walls, forming a distinctive ‘barcode’. This barcode can be accurately dated, providing timelines for various occupations and indicating that Homo sapiens arrived just six months after the Neanderthals vacated the cave. The book reveals that Thorin appears unexpectedly, causing Slimak to express his astonishment, stating, “I did not expect to find a Neanderthal body lying by the roadside, walking through the forest like that. It’s astonishing.”

The jaw of Thorin, a Neanderthal fossil unearthed in 2015

Xavier Muth

This prompts further contemplation about the reasons behind the Neanderthals’ extinction. Although much discussion centers around their decline due to competition with Homo sapiens or climate shifts caused by volcanic eruptions and magnetic field reversals, Slimak offers a fresh perspective. He highlights that the evidence found at Grotte Mandrin points to a layer of small triangular stone points used as arrows by the earliest Homo sapiens, who arrived around 55,000 years ago.

These artifacts bear a striking resemblance to those produced by Homo sapiens at the Ksar Akil site in Lebanon, located nearly 4,000 km away and dating to a similar timeframe. This suggests that these early humans exhibited a far more sophisticated method of sustaining and standardizing practices across extensive social networks, leading Slimak to conclude they had a much more effective “way of life” compared to the Neanderthals, who lived in smaller, isolated groups lacking such consistency.

While one might envision a dramatic battle between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals, the reality was notably different. Slimak draws parallels with the collapse of numerous indigenous communities in post-colonial regions globally, asserting that Neanderthal groups gradually disintegrated when faced with others who possessed a more efficient existence. “The demise of humans reflects the disintegration of their worldview… not through overt violence, but through whispers,” he observes.

“

The bones were painstakingly excavated using tweezers to remove one grain of sand at a time.

“

Although it is profoundly melancholic to ponder, immersing oneself in the realm of these vanished beings through The Last Neanderthal is a unique privilege.

Topic:

- Ancient Humans/

- Book Review

Source: www.newscientist.com