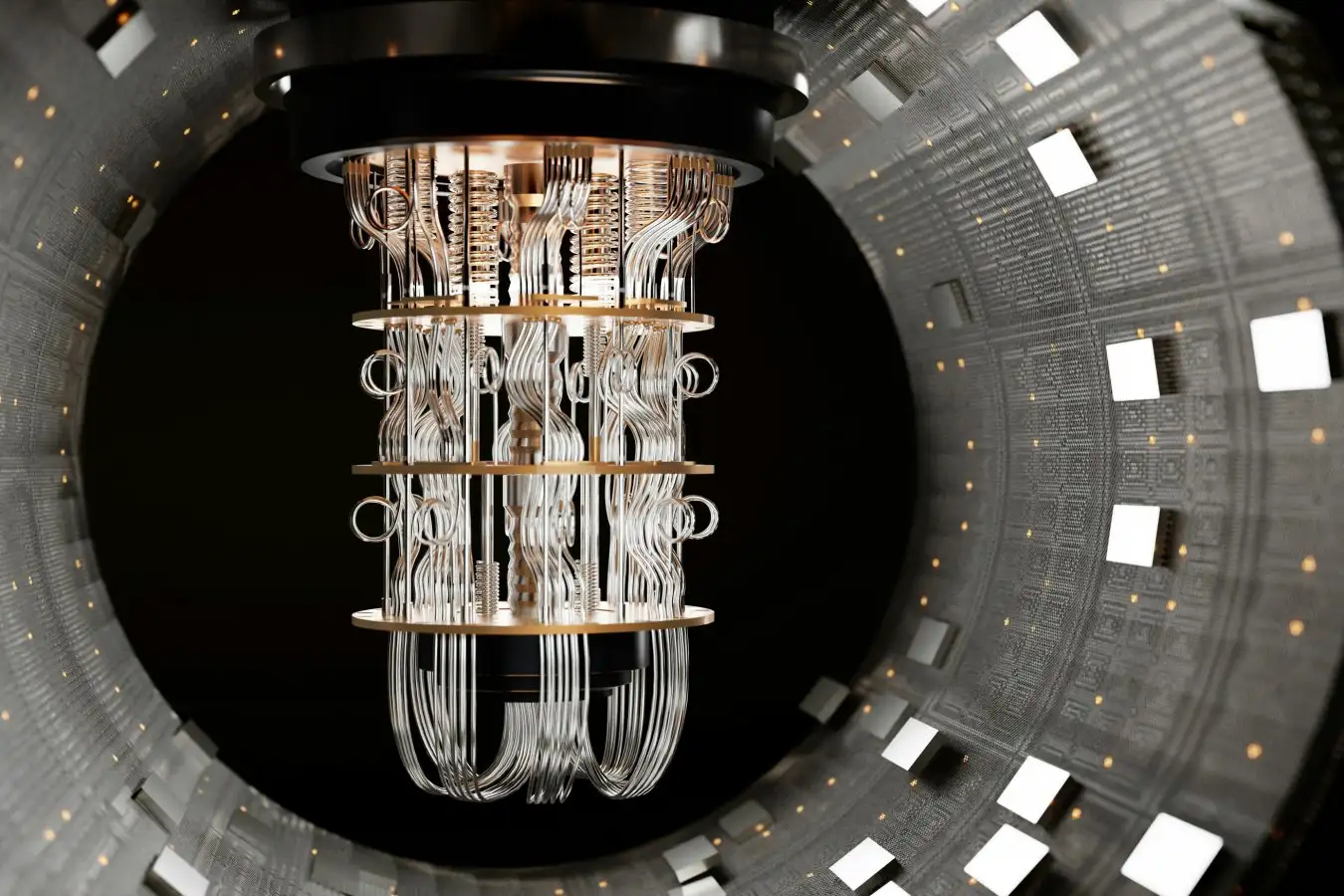

Quantum Computers Could Shed Light on Quantum Behavior Galina Nelyubova/Unsplash

Over the past year, I consistently shared the same narrative with my editor: Quantum computers are increasingly pivotal for scientific breakthroughs.

This was the primary intent from the start. The ambition to leverage quantum computers for deeper insights into our universe has been part of its conception, even referenced in Richard Feynman’s 1981 address. In his discussion about effectively simulating nature, he suggested: “Let’s construct the computer itself using quantum mechanical components that adhere to quantum laws.”

Currently, this vision is being brought to life by Google, IBM, and a multitude of academic teams. Their devices are now employed to simulate reality on a quantum scale. Below are some key highlights.

This year’s advancements in quantum technology began for me with two studies in high-energy particle physics that crossed my desk in June. Separate research teams utilized two unique quantum computers to mimic the behavior of particle pairs within quantum fields. One utilized Google’s Sycamore chip, crafted from tiny superconducting circuits, while the other, developed by QuEra, employed a chip based on cryogenic atoms regulated by lasers and electromagnetic forces.

Quantum fields encapsulate how forces like electromagnetism influence particles across the universe. Additionally, there’s a local structure that defines the behaviors observable when zooming in on a particle. Simulating these fields, especially regarding particle dynamics—where particles exhibit time-dependent behavior—poses challenges akin to producing a motion picture of such interactions. These two quantum computers addressed this issue for simplified versions of quantum fields found in the Standard Model of particle physics.

Jad Halime, a researcher at the University of Munich who was not a part of either study, remarked that enhanced versions of these experiments—simulating intricate fields using larger quantum computers—could ultimately clarify particle behaviors within colliders.

In September, teams from Harvard University and the Technical University of Munich applied quantum computers to simulate two theoretical exotic states of matter that had previously eluded traditional experiments. Quantum computers adeptly predicted the properties of these unusual materials, a feat impossible by solely growing and analyzing lab crystals.

Google’s new superconducting quantum computer, “Willow,” is set to be utilized in October. Researchers from the company and their partners leveraged Willow to execute algorithms aimed at interpreting data obtained from nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, frequently applied in molecular biochemical studies.

While the team’s demonstration using actual NMR data did not achieve results beyond what conventional computers can handle, the mathematics underlying the algorithm holds the promise of one day exceeding classical machines’ capabilities, providing unprecedented insights into molecular structures. The speed of this development hinges on advancements in quantum hardware technology.

Later, a third category of quantum computer made headlines. Quantinuum’s Helios-1, designed with trapped ions, successfully executed simulations of mathematical models relating to perfect electrical conductivity, or superconductivity. Superconductors facilitate electricity transfer without loss, promising highly efficient electronics and potentially enhancing sustainable energy grids. However, currently known superconductors operate solely under extreme conditions, rendering them impractical. Mathematical models elucidating the reasons behind certain materials’ superconducting properties are crucial for developing functional superconductors.

What did Helios-1 successfully simulate? Henrik Dreyer from Quantinuum provided insights, stating that it is likely the most pivotal model in this domain, capturing physicists’ interests since the 1960s. Although this simulation didn’t unveil new insights into superconductivity, it established quantum computers as essential players in physicists’ ongoing quest for understanding.

A week later, I was on another call with Sabrina Maniscalco discussing metamaterials with the quantum algorithm firm Algorithmiq. These materials can be finely tuned to possess unique attributes absent in naturally occurring substances. They hold potential for various applications, ranging from basic invisibility cloaks to catalysts accelerating chemical reactions.

Maniscalco’s team worked on metamaterials, a topic I delved into during my graduate studies. Their simulation utilized an IBM quantum computer built with superconducting circuits, enabling the tracking of how metamaterials manipulate information—even under conditions that challenge classical computing capabilities. Although this may seem abstract, Maniscalco mentioned that it could propel advancements in chemical catalysts, solid-state batteries, and devices converting light to electricity.

As if particle physics, new states of matter, molecular analysis, superconductors, and metamaterials weren’t enough, a recent tip led me to a study from the University of Maryland and the University of Waterloo in Canada. They utilized a trapped ion quantum computer to explore how particles bound by strong nuclear forces behave under varying temperatures and densities. Some of these behaviors are believed to occur within neutron stars—poorly understood cosmic entities—and are thought to have characterized the early universe.

While the researchers’ quantum computations involved approximations that diverged from the most sophisticated models of strong forces, the study offers evidence of yet another domain where quantum computers are emerging as powerful discovery tools.

Nevertheless, this wealth of examples comes with important caveats. Most mathematical models simulated on quantum systems require simplifications compared to the most complex models; many quantum computers are still prone to errors, necessitating post-processing of computational outputs to mitigate those inaccuracies; and benchmarking quantum results against top-performing classical computers remains an intricate challenge.

In simpler terms, conventional computing and simulation techniques continue to advance rapidly, with classical and quantum computing researchers engaging in a dynamic exchange where yesterday’s cutting-edge calculations may soon become routine. Last month, IBM joined forces with several other companies to launch a publicly accessible quantum advantage tracker. This initiative ultimately aims to provide a leaderboard showcasing where quantum computers excel or lag in comparison to classical ones.

Even if quantum systems don’t ascend to the forefront of that list anytime soon, the revelations from this past year have transformed my prior knowledge into palpable excitement and eagerness for the future. These experiments have effectively transitioned quantum computers from mere subjects of scientific exploration to invaluable instruments for scientific inquiry, fulfilling tasks previously deemed impossible just a few years prior.

At the start of this year, I anticipated primarily focusing on benchmark experiments. In benchmark experiments, quantum computers execute protocols showcasing their unique properties rather than solving practical problems. Such endeavors can illuminate the distinctions between quantum and classical computers while underscoring their revolutionary potential. However, transitioning from this stage to producing computations useful for active physicists appeared lengthy and undefined. Now, I sense this path may be shorter than previously envisioned, albeit with reasonable caution. I remain optimistic about uncovering more quantum surprises in 2026.

Topics:

Source: www.newscientist.com