As human space exploration delves deeper into the cosmos, the urgency for sustainable methods to harvest local resources grows, rendering frequent resupply missions increasingly impractical. Asteroids, particularly those abundant in valuable metals like platinum group elements, have become key targets. Recently, scientists conducted a groundbreaking experiment aboard the International Space Station (ISS), utilizing bacteria and fungi to extract 44 elements from asteroid materials in microgravity.

NASA astronaut Michael Scott Hopkins conducts microgravity experiments on the International Space Station. Image credit: NASA.

In this innovative project, known as BioAsteroid, Professor Charles Cockell and his team at the University of Edinburgh utilized the bacterial species Sphingomonas desicabilis and the fungus Penicillium simplicissimum to explore which elements could be extracted from L-chondrite asteroid materials.

Understanding microbial interactions with rocks in microgravity is equally essential.

“This is likely the first experiment of its nature using a meteorite on the International Space Station,” states Dr. Rosa Santomartino, a researcher at Cornell University and the University of Edinburgh.

“Our aim was to customize our methodology while ensuring it remained broadly applicable for enhanced efficacy.”

“These two species behave uniquely and extract varied elements.”

“Given the limited knowledge on microbial behavior in space, we aimed to keep our results universally applicable.”

These microorganisms present promising solutions for resource extraction, as they generate carboxylic acids—carbon molecules that bind to minerals and promote their release through complex formation.

Nonetheless, many questions linger regarding this mechanism, leading researchers to conduct a metabolomic analysis. This analysis involved examining liquid cultures from completed experimental samples, focusing on the presence of biomolecules, particularly secondary metabolites.

NASA astronaut Michael Scott Hopkins conducted experiments aboard the ISS to examine microgravity’s effects, while researchers performed controlled experiments on Earth for comparative data.

Substantial data analysis yielded insights into 44 different elements, 18 of which were biologically derived.

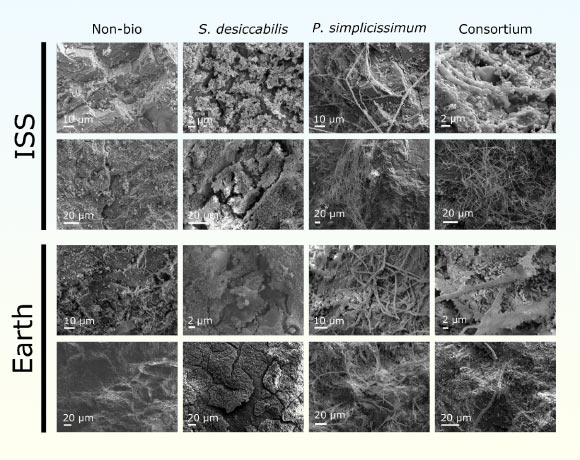

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of L-chondrite fragments under two gravity conditions. Image credit: Santomartino others., doi: 10.1038/s41526-026-00567-3.

“We drilled down to a single-element analysis and began to question whether extraction processes differ in space versus Earth,” notes Dr. Alessandro Stilpe from Cornell University and the University of Edinburgh.

“Do more elements get extracted in the presence of bacteria, fungi, or both?”

“Is this merely noise? Or do we observe coherent patterns? Differential outcomes were modest but intriguing.”

The analysis highlighted significant metabolic changes in microorganisms, particularly fungi, in space, leading to increased production of carboxylic acids and promoting the release of elements like palladium and platinum.

For several elements, abiotic leaching proved less effective in microgravity compared to Earth, while microorganisms demonstrated consistent extraction results across both environments.

“Microorganisms do not enhance extraction rates directly but maintain extraction levels regardless of gravity,” explains Dr. Santomartino.

“This finding is applicable to not just palladium but many metals, though not all.”

“Interestingly, extraction rates varied significantly by metal type, influenced by microbial and gravitational conditions.”

For detailed insights, refer to the results published in npj microgravity.

_____

R. Santomartino others. Microbial biomining from asteroid material on the International Space Station. npj microgravity published online on January 30, 2026. doi: 10.1038/s41526-026-00567-3

Source: www.sci.news