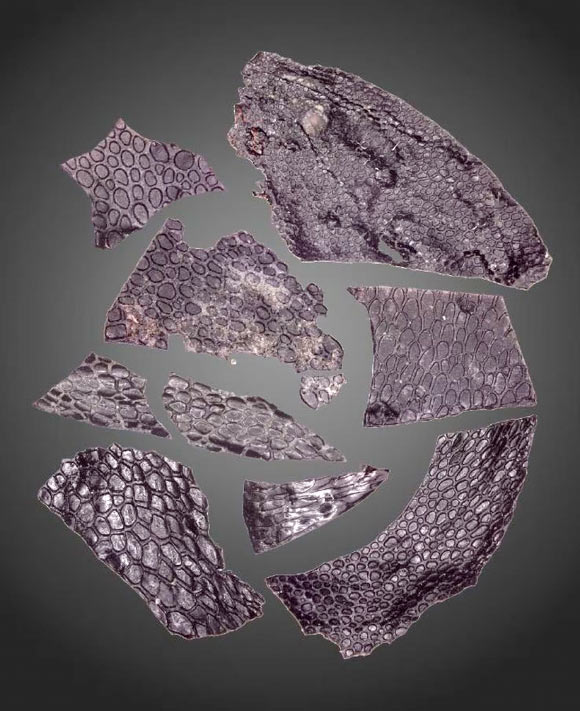

Fossilized skin fragments collected from the Richards Spur Cave system in Oklahoma, US, are at least 21 million years older than any previously reported skin fossil.

The newly described fossilized skin is captorinus agutia type of early reptile that lived during the Permian period about 289 million years ago.

This reptile specimen and associated skeleton were collected by long-time paleontology enthusiasts Bill and Julie May. Richards Spara limestone cave system in Oklahoma that is currently undergoing quarrying.

The skin fragments are smaller than fingernails and have a pebble-like surface, most similar to crocodile skin.

This is the earliest preserved example of the epidermis, the outermost layer of skin, in terrestrial reptiles, birds, and mammals, and was an important evolutionary adaptation in the transition to terrestrial life.

“Every once in a while, we have a unique opportunity to glimpse deep into time,” said Ethan Mooney, a graduate student at the University of Toronto.

“Discoveries of this kind can really enrich our understanding and appreciation of these pioneering animals.”

Skin and other soft tissue rarely fossilize, but Mooney and colleagues say that this is possible thanks to unique features of the Richards Spur Cave system, including fine clay deposits that slow decomposition, oil seepage, and a cave environment. We believe that in this case it was possible to save the skin. It was probably an environment without oxygen.”

“Animals would have fallen into this cave system during the early Permian period and become buried in very fine clay sediments, slowing down the process of decay,” Mooney said.

“What is surprising, however, is that this cave system was also the site of an active oil seepage during the Permian, and the interaction of the hydrocarbons in the oil with the tar is likely what enabled the preservation of this surface. is.”

Analysis of the specimens revealed epidermal tissue, a characteristic of the skin of amniotes, a group of terrestrial vertebrates that includes reptiles, birds and mammals that evolved from amphibian ancestors during the Carboniferous Period.

“What we saw was completely different from what we expected, so we were in complete shock,” Mooney said.

“Finding ancient skin fossils like this is a unique opportunity to peer into the past and learn what the skin of these early animals looked like.”

The skin shares features with ancient and extant reptiles, including a pebble surface similar to crocodile skin and hinge areas between epidermal scales similar to the skin structure of snakes and earthworm lizards.

However, because the skin fossils are not associated with skeletons or other artifacts, it is not possible to determine which species or body part the skin belonged to.

The fact that this ancient skin resembles the skin of reptiles living today shows how important these structures are for survival in terrestrial environments.

“The epidermis was an important feature for vertebrates to survive on land. It is an important barrier between internal processes and the harsh external environment,” Mooney said.

“This skin may represent the skin structure of an early amniote terrestrial vertebrate ancestor that allowed for the eventual evolution of feathers in birds and hair follicles in mammals.”

of findings appear in the diary current biology.

_____

Ethan D. Mooney other. Paleozoic cave systems preserve the earliest known evidence of amniote skin. current biology, published online on January 11, 2024. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2023.12.008

Source: www.sci.news