cloned rhesus monkey

Zhaodi Liao et al.

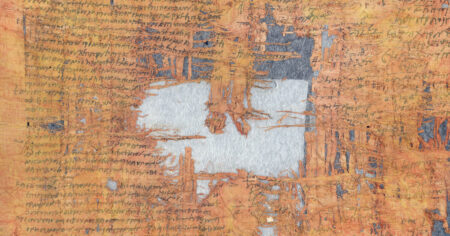

After many years and many attempts, a healthy rhesus monkey was finally created by cloning. The clone was born in China on July 16, 2020, but its existence has only now been revealed.

“The cloned rhesus macaque is now 3 years old,” team members say Fallon Lu at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing. “So far, no health problems have been found during routine medical examinations.”

However, because the monkeys were cloned from fetal cells rather than adult cells, the embryos had to be provided with a non-cloned placenta. Therefore, despite this progress, primate cloning remains extremely difficult. As a result, apart from ethical and legal issues, it may not yet be technically possible to clone an adult.

Cloning is the creation of an individual that is genetically identical to another individual. Cloning plants is easy, but for most animals it is much more difficult.

Dolly the sheep, the first mammal cloned from an adult cell, was born in 1996. Since then, researchers have attempted to clone many mammalian species, with mixed results.

In some cases, cloning works relatively well.A Korean team created a clone over 1500 dogs For example, so far, success rates remain low, with fewer than 4 percent of cloned embryos leading to live births. In many other mammalian species, cloning either fails completely or produces unhealthy animals.

The main problem is that as cells in the body develop and become specialized, various so-called epigenetic markers are added to the DNA in order to turn certain genes on or off. When adult cells are cloned into empty eggs, they usually contain the wrong epigenetic markers.

Primates (a group that includes apes such as monkeys and humans) have proven particularly difficult to treat. There have been several previous reports of monkey clones, but each case so far has come with major warnings.

For example, the rhesus macaque born in 1999 is sometimes described as the first primate clone, but this individual was created not by cloning adult cells like Dolly, but by creating identical twins. It was created by splitting the embryo, as is done.

In 2022, rhesus macaques will be born. cloned from a genetically modified adult However, this clone died shortly after birth.

The most successful attempt to date was the birth of two long-tailed macaques in 2017. The researchers behind this study used a chemical cocktail to help reset epigenetic markers, but they were still able to clone only fetal cells, not adult cells.

Lu's team tried applying the same cocktail to rhesus macaques, but the only clone produced this way did not survive. The researchers concluded that the abnormalities in the cloned placenta were partially to blame, and decided to transplant the part of the early embryo that turns into a fetus (the inner cell mass) into a non-cloned embryo, where the inner cell mass forms. Developed new technology. Cell clumps were removed.

This means that the cloned fetus develops within a non-cloned placenta that is genetically distinct from it. Theoretically, the resulting fetuses could be a mixture of clonal and non-clonal cells, but the researchers found no evidence of such chimerism.

But even with the help of this complex technique, the researchers have so far only cloned fetal cells and not adult cells. In other words, healthy primates have not yet been created by cloning adult cells.

This means that whether it is possible to clone adults remains an open question. Lu wouldn't speculate on whether his team's technique would help.

“The act of cloning humans is completely unacceptable. We don't think about this,” he says.

Shukrat Mitalipov A professor at Oregon Health & Science University, who also works on cloning but was not involved in the study, says it's unclear whether the technology will help create cloned humans. “Aside from ethical issues, it is unclear whether there is any humanity. [cloned] “The fetus has placental abnormalities,” Mitalipov said.

Lu says the purpose of primate cloning is to advance research. “Rhesus monkeys are important and commonly used non-human primate laboratory animals in cognitive and biomedical research,” he says.

Meanwhile, Mitalipov's aim is to use cloning to generate stem cells that are compatible with individual treatments. “In our case, one day doctors will be able to use non-rejection, genetically compatible embryonic stem cells to replace diseased nerve, muscle, blood and other cells, or to produce eggs for infertility treatment. I hope we can produce it,” he says.

topic:

Source: www.newscientist.com