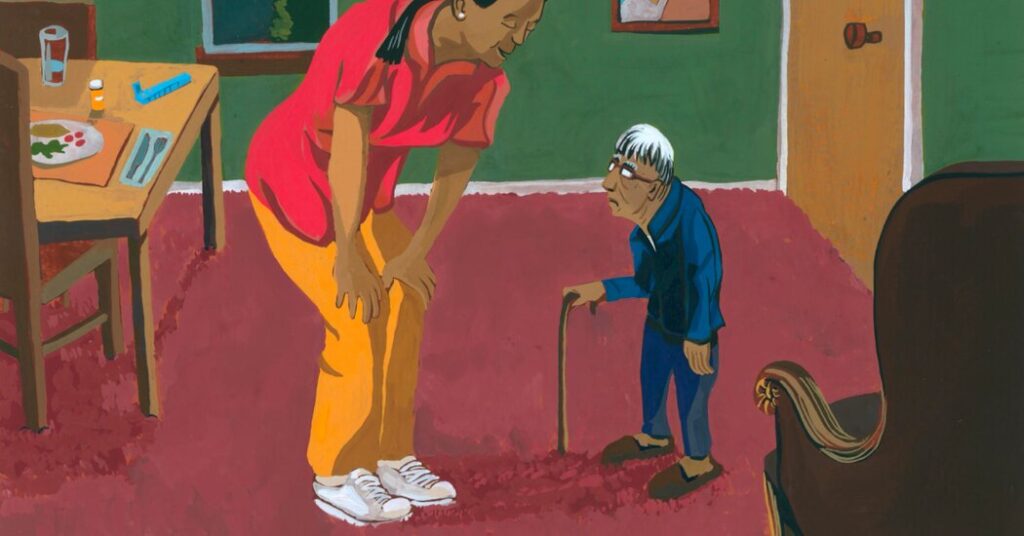

An illustrative instance of Elderspeak: Cindy Smith was spending time with her father in his assisted living apartment located in Roseville, California.

“He just shot her a look from beneath his bushy brows and asked, ‘What are we, married?'” she recounted.

Her father, 92 years old, was a former county planner and a World War II veteran. Although macular degeneration affected his eyesight and he navigated with caution, his cognitive faculties remained sharp.

“He usually isn’t very placid with others,” Smith noted. “But he felt he was an adult, and he often wasn’t treated as such.”

Most people intuitively grasp what “Elderspeak” entails. “What resembles baby talk is often directed toward the elderly,” stated Clarissa Shaw, a dementia care researcher and co-author affiliated with the University of Iowa College of Nursing. Recent Articles document its prevalence in research.

“It emerges from ageist assumptions of fragility, incapability, and reliance.”

This aspect may also involve inappropriate affection. “Elderspeak behaves like a superior, incorporating terms like ‘honey,’ ‘dearie,’ and ‘sweetie’ to dulcet the communication,” remarked Kristine Williams, a nurse gerontologist from the University of Kansas’s Faculty of Nursing and another co-author.

“We hold negative stereotypes about older individuals, prompting changes in our speech.”

Alternatively, caregivers might resort to using various pronouns. Are you ready for a bath? In this case, “they don’t act as individuals,” Dr. Williams explained. “I certainly hope I’m not bathing with you.”

Occasionally, Elderspeakers utilize loud, brief sentences or simple words delivered slowly. They may also employ an exaggerated singing tone more fitting for children, using terms like “toilet” or “jammies.”

With the so-called tag question – It’s lunchtime now, right? – “You’re posing questions but not allowing them to answer,” Dr. Williams clarified. “You’re telling them how to respond.”

Research in nursing homes highlights how prevalent such speech patterns are. This was evident when Dr. Williams, Dr. Shaw, and their team evaluated video recordings of 80 engagements between staff and dementia patients, finding that 84% involved some variant of Elderspeak.

“Most Elderspeak is well-meaning. People genuinely aim to assist,” Dr. Williams noted. “They fail to recognize the negative implications inherent in it.”

For instance, research among dementia patients in nursing homes has identified a correlation between exposure to Elderspeak and behaviors collectively referred to as resistance to care. Research indicates.

“Individuals might turn away, cry, or refuse,” Dr. Williams elucidated. “They could close their mouths during feeding attempts.” Some may even push caregivers away or become aggressive.

She and her team created a training initiative called Chat (Change Talk), a three-hour session that incorporates videos of communication between staff and patients, aiming to mitigate the use of Elderspeak.

The initiative proved effective. Prior to the training, encounters in 13 nursing homes located in Kansas and Missouri revealed that roughly 35% of staff interactions involved Elderspeak. This figure has now dropped to around 20%.

Simultaneously, resistance behaviors constituted nearly 36% of interaction time. Post-training, this percentage decreased to approximately 20%.

Additionally, a study carried out at Midwest Hospital found the same decline in resistance behaviors among dementia patients. The findings indicated.

Furthermore, the implementation of chat training in nursing homes was linked to a reduction in antipsychotic medication usage. While the results did not achieve statistical significance, they were deemed “clinically significant” by the researchers due to the small sample sizes involved.

“Many of these medications carry a black box warning from the FDA,” Dr. Williams mentioned. “Their use in frail elderly populations can be perilous due to potential side effects.”

Currently, Dr. Williams, Dr. Shaw, and their colleagues have streamlined the chat training for online implementation. They are assessing its effectiveness across around 200 nursing homes nationwide.

Even without a structured program, individuals and organizations can combat Elderspeak. Kathleen Carmody, the owner of Senior Matters Home Care and Consulting in Columbus, Ohio, suggests that when addressing clients, one should use titles like Mr. or Mrs., unless instructed otherwise.

However, in long-term care settings, families and residents may express concerns that altering staff communication could lead to resentment.

A few years ago, Carol Fahe dealt with a mother who was vision-impaired at an assisted living facility near Cleveland, becoming increasingly dependent in her 80s.

She described staff members who called her mother “sweetie” and “honey,” hovering over her while tying her hair in pigtails, likening the treatment to how toddlers are treated, said Fahe, 72, a psychologist from Kaneohe, Hawaii.

She recognized the aides meant well, but “there’s a misleading notion associated with that,” she reflected. “It doesn’t feel good for anyone. It’s isolating.”

Fahe contemplated addressing her concerns with the aide but hesitated, fearing retaliation. Ultimately, she moved her mother to a different facility for various reasons.

However, opposing Elderspeak doesn’t need to be confrontational, Dr. Shaw emphasized. Residents, patients, and individuals encountering Elderspeak elsewhere can respectfully express their preferences regarding how they wish to be addressed and what names they prefer, which is often applicable beyond healthcare environments.

Cultural variances also play a significant role. Felipe Agudero, a health communication educator at Boston University, pointed out that in specific contexts, endearing terms or phrases “aren’t rooted in underestimating someone’s intellect. They represent affection.”

Having moved from Colombia, he noted that his 80-year-old mother does not take offense when a physician or healthcare staff asks her to “Tómesela pastilita” (take this little pill) or “Muévanlas manitas” (move your little hands).

Such expressions are customary and “she feels as though she’s conversing with someone who cares,” Dr. Agudero conveyed.

“Arrive at a place of negotiation,” he advised. “There’s no need for confrontation. Patients have every right to state, ‘I prefer not to be spoken to in that manner.’ “

In response, professionals should “acknowledge that the recipient may not share the same cultural background,” he noted, adding, “This is how I communicate, but I can adapt.”

Lisa Graeme, 65, a retired writer from Alvada, Colorado, recently confronted Elderspeak when she enrolled in Medicare drug coverage.

She recalled receiving nearly daily calls from mail-order pharmacies, following their failure to meet her prescription needs.

These “overly sweet” callers seemed to follow a script, addressing her as “Mr. Graeme,” as if they were administering medication.

Frustrated by their assumptions and their probing questions about her medication adherence, Ms. Graeme informed them that she had sufficient stock, thanks. She organizes her own refills.

“I asked them to cease calling,” she recounted. “And they did.”

The New Old Age, KFF Health News.

Source: www.nytimes.com