For residents of the West Coast, the weather event known as the atmospheric river, stretching from San Diego to Vancouver, can deliver winter-like conditions similar to those in Boston, with heavy rain and snowfall.

Much like the storms that affect the East Coast, the term “Atmospheric River” can often feel trendy. While it may resonate more with those walking the streets of San Francisco than just plain “heavy rain,” it precisely describes moisture-laden storms in the Pacific Ocean that release precipitation upon hitting the mountain ranges in Washington, Oregon, and California.

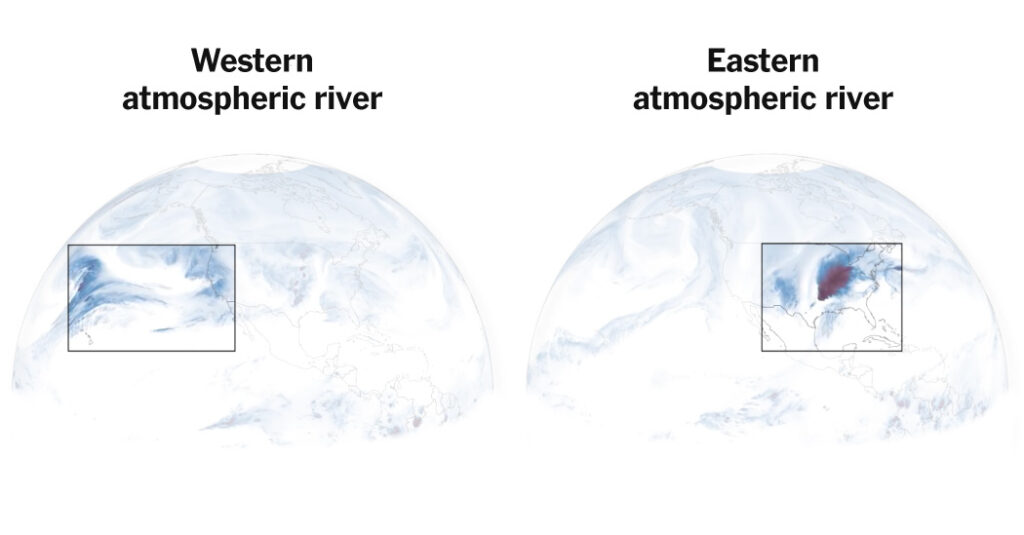

Yet, these plumes of highly humid air driven by strong winds are not exclusive to the West Coast. They can occur globally, and recently, meteorologists and scientists are starting to apply this term to storms occurring east of the Rocky Mountains. This spring, a series of heavy rains in the central and southern United States resulted in fatal floods, with Accuweather identifying the unusual weather phenomenon as an Atmospheric River. CNN did as well.

Some researchers are hopeful that the term will gain wider acceptance, although not all meteorologists, including those at the National Weather Service, are on board. The crux of the debate revolves around how forecasts will describe the conditions for the day.

The Atmospheric River can stretch up to 2,000 miles.

These weather systems typically form over oceans in tropical and subtropical regions, where water vapor evaporates and coalesces into extensive streams of steam that travel through the lower atmosphere towards the poles. Averaging around 500 miles wide and extending up to 1,000 miles, while many weak atmospheric rivers bring beneficial precipitation, stronger ones can lead to severe rainfall, causing flooding, landslides, and significant destruction.

Rain is not the only aspect; just as squeezing a wet sponge releases water, atmospheric rivers require a mechanism to shed rain and snow. As they ascend, the water vapor cools, condenses, and ultimately falls as precipitation.

On the West Coast, this process repeats from late fall to early spring, facilitated by mountain ranges such as the Cascade and Sierra Nevada, which provide the necessary lift. Atmospheric rivers from the Pacific Ocean collide with these mountains, forcing the water vapor upward where it turns into liquid.

The situation is more complex in other regions, where upward lift usually arises from less defined and unpredictable atmospheric instability rather than geographical features. In early April, for example, cold air descending from the north pushed under the Atmospheric River originating from the bay, elevating the moist air.

“When warm air is forced up to a higher elevation than its surroundings, it can rapidly ascend, leading to severe thunderstorms,” explained Travis O’Brien, an assistant professor at Indiana University and co-author of a noteworthy paper. This study garnered attention regarding Atmospheric Rivers impacting the Midwest and East Coast.

Regions like Kentucky, Tennessee, and Arkansas experienced extreme flooding, with rainfall exceeding 15 inches in some areas.

So, why is it called that?

Atmospheric rivers have existed for ages; however, scientists began recognizing and naming them in the mid-1970s to 1980s with advancements in satellite technology, specifically the global operating environment satellite known as GOES, developed by NASA and administered by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Clifford Masa, a professor of atmospheric science at the University of Washington, noted, “Prior to that, we didn’t discuss it much.”

Advancements in satellite technology allowed researchers and meteorologists to visualize atmospheric rivers, leading to more discussions and the formal naming of the phenomenon.

The term “Atmospheric River” was introduced in the 1990s by two scholars at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology: meteorologist Reginald E. Newell and research scientist Yong Zhu. They originally referred to it as Tropospheric River, named after the lowest layer of the Earth’s atmosphere where most weather phenomena occur. It later evolved into “Atmospheric River,” as it was noted that these rivers “carry about the same amount of water as the Amazon.”

Is the terminology overused? Sometimes.

Though the term became more prominent in the 2010s to 2020s, it primarily gained traction on the West Coast, as scientists focused on and studied atmospheric rivers. Numerous research papers identified them as a key source of rain and snow across California, Oregon, and Washington, as well as major contributors to flooding events. One notable occurrence was a series of nine atmospheric rivers that inundated California in December 2022 and January 2023, resulting in widespread flooding and alleviating drought conditions.

Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at the University of California, Los Angeles, highlighted that interest in atmospheric rivers tends to peak during California’s exceptionally wet storm seasons. While he appreciates the label, he also points out its potential misuse, stating that excessive use can mislead the public if distinctions between different atmospheric river intensities are not made.

“The primary misconception is that every atmospheric river is an extreme and destructive event, which is not accurate,” Swain explained.

A classification system for atmospheric rivers was introduced in 2019 to clarify this confusion. Dr. Marty Ralph, director of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego and the Center for Extreme Weather and Water in the West, spearheaded the development of this classification system, which has been applied in various global regions including the Arctic and Antarctic. He has been a prominent advocate for researching and popularizing the term atmospheric river, particularly in California, authoring numerous papers on the topic.

“It was Marty Ralph who convened the scientific community around the concept of Atmospheric Rivers as a topic deserving of attention, and his efforts have implicitly tied this concept to the West Coast, despite the original studies being global in scope,” Dr. O’Brien remarked.

This association may mislead the public as daily forecasts from West Coast offices frequently discuss atmospheric rivers, whereas offices in other regions may not.

“In the Midwest and Southeast, we typically don’t use that terminology,” stated Jimmy Barham, lead meteorologist with the Arkansas Meteorological Service. “We simply refer to it as higher-level moisture.”

The focus on the West Coast also means that atmospheric rivers are studied less frequently in other regions, where hurricanes and summer thunderstorms also contribute significantly to rainfall and draw considerable attention.

Dr. Ralph aspires for expanded research to reach the East Coast, asserting, “Even the East Coast often experiences strong, potentially impactful atmospheric rivers.”

Source: www.nytimes.com