Pterosaurs often glide above dinosaurs, but recent analysis of fossilized footprints indicates that some of these flying reptiles were equally adept at traversing the ground.

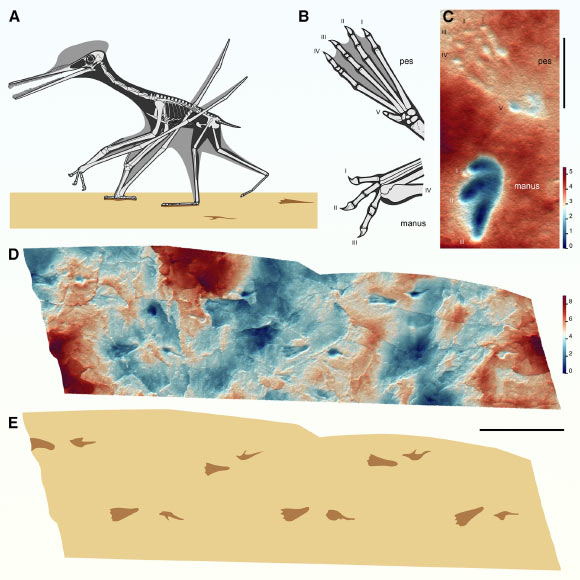

Terrestrial migration and tracking morphology of vegetative eye type skeletal morphology: (a) Reconstruction of the ctenochasmatoid orbit Ctenochasma elegans walking with ipsilateral gait, where the fore and hind legs on the same side of the body move together. (b) Manual and pedal morphology of Ctenochasma elegans; PES is plant and pentadactyl, while Manus is digital grade, functionally triductyl as the large fourth digit supporting the outer wing is folded during terrestrial movement. (c) Height map of pterosaur manus and PES footprints in the holotype of Ichnotaxon Pteraichnus stokesi that matches Ctenochasma elegans; (d) height maps from the Pterosaur trackway; Pteraichnus ISP. From the Upper Jurassic Casal Formation of Claysac, France. An outline drawing of (e) interpretation Pteraichnus ISP. Scale bar – 20 mm in (c), 200 mm in (d) and (e). Image credit: Smith et al., doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2025.04.017.

“We have been diligently working to enhance our understanding of their lives,” stated Robert Smith, a doctoral researcher at the University of Leicester.

“These footprints offer insights into their habitat, movement, behaviors, and activities in ecosystems long gone.”

In this study, Smith and colleagues uncovered three distinct types of pterosaur footprints, each elucidating various lifestyles and behaviors.

Tying these footprints to specific groups presents a valuable new avenue for exploring how these flying reptiles lived, migrated, and adapted over time across different ecosystems.

“At last, 88 years after the initial discovery of Pterosaur tracks, we understand precisely who made them and the methods employed,” remarked Dr. David Unwin, Ph.D., from Leicester.

The most striking finding emerged from a group of pterosaurs known as Neoazdalci. Quetzalcoatlus, one of the largest flying creatures, boasts a wingspan of 10 meters.

Their footprints have been found in both coastal and inland regions worldwide, supporting the notion that these tall creatures not only ruled the skies but also cohabited the same environments as many dinosaur species.

Some of these tracks date back to an asteroid impact event 66 million years ago, alongside the extinction of both pterosaurs and dinosaurs.

Ctenochasmatoids, recognized for their elongated jaws and needle-like teeth, predominantly left tracks in coastal sediments.

These animals likely traversed muddy shores or shallow lagoons, employing specialized feeding techniques to capture small fish and floating prey.

The prevalence of these tracks indicates that these coastal pterosaurs were far more common in these habitats than the infrequent fossil remains suggest.

Another type of footprint was unearthed in rock formations, alongside the fossilized skeleton of the same pterosaur.

The close correlation between footprints and skeletons provides compelling evidence for identifying the print makers.

Known as Dsungaripterids, these pterosaurs featured robust limbs and jaws; the tips of their curved, toothless beaks were designed for grasping prey, while the large, rounded teeth at the rear of the jaw were ideal for crushing shellfish and other resilient foods.

“Footprints are frequently overlooked in Pterosaur studies, yet they yield a wealth of information regarding their behavior, interactions, and environmental relationships,” stated Smyth.

“A comprehensive analysis of the footprints enables us to uncover biological and ecological insights that cannot be obtained elsewhere.”

The team’s paper is published in the journal Current Biology.

____

Robert S. Smith et al. Identifying Pterosaur track makers provides important insights into Mesozoic ground invasions. Current Biology Published online May 1, 2025. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2025.04.017

Source: www.sci.news