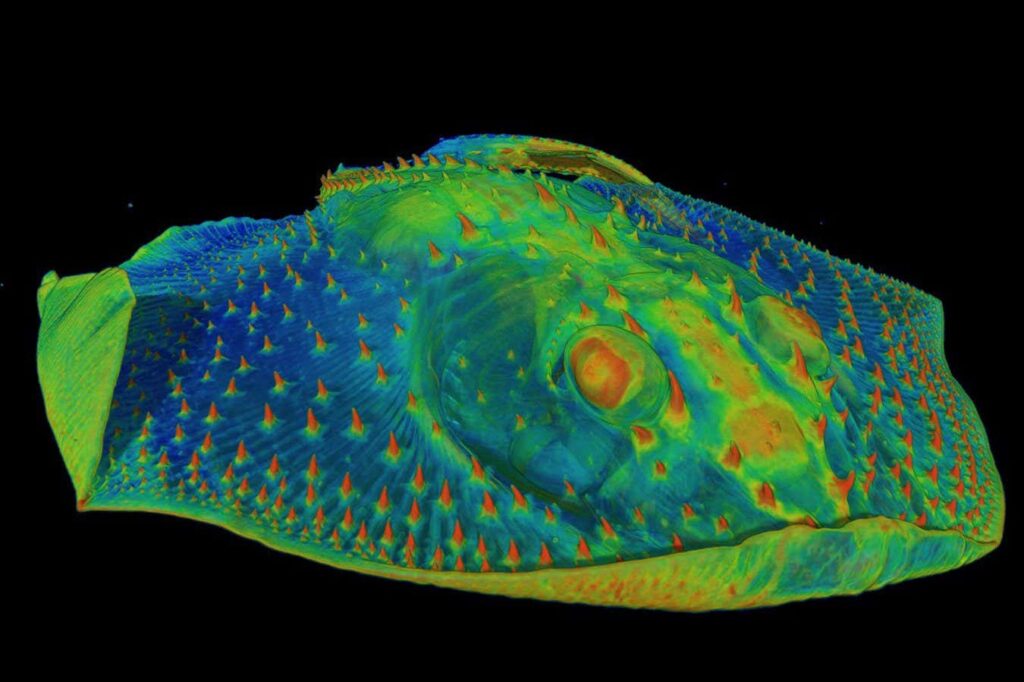

CT scan of the front of a skate depicting a hard, tooth-like dentition (orange) on its skin

Yara Haridi

Recent analysis of animal fossils suggests that teeth initially developed as sensory organs rather than for chewing. The earliest tooth-like structure seems to have originated as a sensitive nodule in the skin of primitive fish, allowing them to detect variations in the surrounding water.

The findings support the long-held belief that teeth originally evolved outside the mouth, as noted by Yara Haridi from the University of Chicago.

While some evidence exists to back this theory, significant questions remain. “What purpose do all these teeth on the exterior serve?” queries Khalidi. One possibility is that they functioned as defensive armor; however, Khalidi proposes an additional theory: “It’s beneficial to protect oneself with tough materials, but imagine if those materials could also enhance sensory perception of the environment?”

True teeth are exclusively found in vertebrates, such as fish and mammals. Although some invertebrates possess dental structures, their underlying tissues are fundamentally different. This indicates that teeth originated with the evolution of the earliest vertebrates: fishes.

Khalidi and her research team scrutinized fossils claimed to be the oldest examples of fish teeth, utilizing advanced synchrotron scanning techniques.

They examined fragments of fossils from the genus Anatrepis, which spanned from the late Cambrian (539 to 487 million years ago) to the early Ordovician period (487 to 443 million years ago). These organisms featured a hard exoskeleton with perforations.

These perforations were interpreted as dentin tubules, which are one of the hard tissues composing teeth. In human teeth, dentin serves multiple functions, including sensation and the detection of temperature and pain.

This led to the hypothesis that these tubules may be the precursors of teeth. Anatrepis represents early fish.

However, Haridi and her colleagues found no such evidence. “We observed the internal structure [of the tubules],” she states. Their examination revealed that the tubules most closely resemble structures known as sensilla, which are found in the exoskeletons of insects and spiders.

This means that Anatrepis are arthropods rather than fish, implying that their tubules do not directly lead to the evolution of teeth.

“Dentin likely emerged as a novel feature in vertebrates, but the hardened external sensory capabilities existed much earlier in invertebrates,” remarks Gareth Fraser from the University of Florida, who was not involved in the research.

Beyond Anatrepis, the earliest known true teeth belong to Ellipticus, which dates exclusively to the Ordovician period. These possess actual dentin found in the skin’s teeth.

Khalidi suggests that like the invertebrate Anatrepis, early vertebrates such as Ellipticus evolved independently to develop skin structures, where sensory nodules had undergone significant evolution. “These two entirely different organisms had to navigate the ancient ocean’s muddy terrain,” she explains. Significantly, the study also indicates that some modern fish skin still retains nerve endings, indicating sensory functionality.

As certain fish transitioned into active predators, they required a method for securing prey, leading to the evolution of hard teeth that moved to their mouths for biting.

“Based on the available data, tooth-like structures may have initially evolved in the skin of ancient vertebrates before migrating into the mouth, evolving into teeth,” Fraser concludes.

topics:

Source: www.newscientist.com