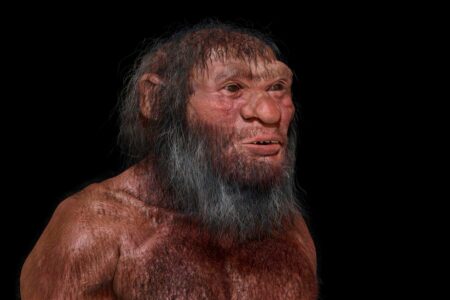

For over 20 years, Sahelanthropus tchadensis, one of the earliest hominid species (dating back 6.7 to 7.2 million years), was discovered in Chad in 2001. This species is central to a heated debate: Did our earliest ancestors walk upright? A groundbreaking study by paleoanthropologists at New York University provides compelling evidence supporting this notion. The research indicates that Sahelanthropus tchadensis, an ape-like ancestor from Africa, showcases some of the earliest adaptations for bipedal terrestrial locomotion.

According to New York University, “Sahelanthropus tchadensis was essentially a bipedal ape with a brain size similar to that of a chimpanzee, likely spending considerable time foraging and finding safety in trees,” as noted by Dr. Scott Williams.

“Despite its ape-like appearance, Sahelanthropus tchadensis demonstrated adaptations for bipedal posture and movement on land,” Dr. Williams added.

The team focused on the femur and two partial forearm bones found at the Toros Menara site in Chad. Previous research had asserted that these bones were too ape-like to indicate upright walking; however, this latest study utilizes 3D shape modeling and anatomical analysis tailored to human locomotion.

“These characteristics suggest a similarity in hip and knee function between Sahelanthropus tchadensis and modern humans, possibly representing fundamental adaptations toward bipedalism in the human lineage,” the researchers concluded.

Although the external shape of the limb bones resembles that of chimpanzees, the proportions indicate a more human-like configuration.

The researchers found that the relationships between arm and leg lengths are comparable to modern bonobos and early human predecessors.

Notably, they discovered the femoral tubercle—a bony structure on the femur crucial for attaching the iliofemoral ligament, which stabilizes the human hip joint—unique to hominids.

Additionally, the femur exhibited significant internal torsion known as front twist (medial torsion of the femoral shaft), a feature linked to aligning the knee with the body’s center of gravity during walking, distinctly present in hominids compared to extant apes and extinct Miocene species.

These findings challenge long-held beliefs regarding the timeline and mechanics of upright walking evolution.

Scientists propose that bipedalism emerged gradually rather than as a sudden change. “We consider the evolution of bipedalism as an ongoing process,” researchers stated.

“Sahelanthropus tchadensis could represent an early form of habitual bipedalism.”

“In addition to terrestrial bipedalism, Sahelanthropus tchadensis likely engaged in various arboreal activities, including vertical climbing, forelimb suspension from branches, and both arboreal quadrupedal and bipedal locomotion.”

The study interprets this fossil as evidence of early human evolution from an ape-like ancestor, asserting that chimpanzee-like species are positioned near the root of the human family tree.

“Our analysis reveals that Sahelanthropus tchadensis demonstrates an early adaptation for bipedalism, suggesting that this trait evolved early in our lineage from ancestors closely related to present-day chimpanzees and bonobos,” Dr. Williams stated.

For further details, refer to the study published in this month’s issue of Scientific Advances.

_____

Scott A. Williams et al., 2026. The Earliest Evidence of Bipedalism in Humans: Sahelanthropus tchadensis. Scientific Advances 12(1); doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adv0130

Source: www.sci.news