On Earth, we may not often realize it, but the sun regularly ejects massive clumps of plasma into space known as coronal mass ejections (CMEs). Astronomers, utilizing the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope along with ground-based telescopes in Japan and South Korea, have begun to detect signs of multi-temperature CMEs. EK Draconis, a young G-type main sequence star, is located 112 light-years away in the northern constellation Draco.

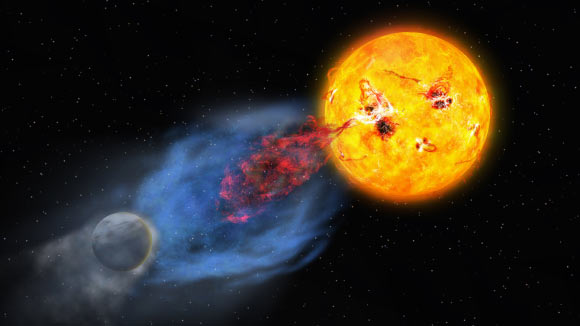

Artist’s depiction of the coronal mass ejection from EK Draconis. Image provided by: National Astronomical Observatory of Japan

“Researchers believe that CMEs may have significantly impacted the development of life on Earth, given that the Sun was quite active in its early days,” stated Kosuke Namegata, an astronomer at Kyoto University, along with his colleagues.

“Historically, studies have indicated that young stars similar to our Sun often produce intense flares that surpass the largest solar flares recorded in contemporary times.”

“The massive CMEs from the early Sun could have drastically influenced the primordial conditions on Earth, Mars, and Venus.”

“Nevertheless, the extent to which these youthful stellar explosions produce solar-like CMEs remains uncertain.”

“Recent years have seen the detection of cold plasma in CMEs via ground-based optical methods.”

“However, the high speeds and frequent occurrences of significant CMEs predicted in earlier studies have yet to be confirmed.”

In their investigation, the authors concentrated on EK Draconis, a youthful solar analog estimated to be between 50 million and 125 million years old.

Commonly referred to as EK Dra and HD 129333, the star shares effective temperature, radius, and mass characteristics that make it an excellent analog for the early Sun.

“Hubble captured far-ultraviolet emission lines sensitive to high-temperature plasma, while three ground-based telescopes simultaneously recorded hydrogen alpha lines tracking cooler gas,” the astronomers explained.

“These synergistic multi-wavelength spectroscopic observations enabled us to observe both the hot and cold components of the eruption instantaneously.”

This research presents the first evidence of a multitemperature CME originating from EK Draconis.

“Our findings indicate that high-temperature plasma at around 100,000 K was ejected at speeds ranging from 300 to 550 km/s, followed approximately 10 minutes later by a lower-temperature gas around 10,000 K ejected at a speed of 70 km/s,” the astronomers reported.

“The hotter plasma contained significantly more energy than the cooler plasma. This implies that frequent intense CMEs in the past may have sparked strong shocks and high-energy particles capable of eroding or chemically altering the early atmospheres of planets.”

“Theoretical and experimental research suggests that robust CMEs and high-energy particles could play a key role in generating biomolecules and greenhouse gases vital for the emergence and sustainability of life on early planets.”

“Consequently, this discovery carries substantial implications for understanding the habitability of planets and the conditions under which life may have arisen on Earth—and potentially elsewhere.”

The team’s study was published in the journal Nature Astronomy.

_____

Namekata K. et al. Signs of multi-temperature coronal mass ejections identified in a young solar analog. Nat Astron published online on October 27, 2025. doi: 10.1038/s41550-025-02691-8

Source: www.sci.news