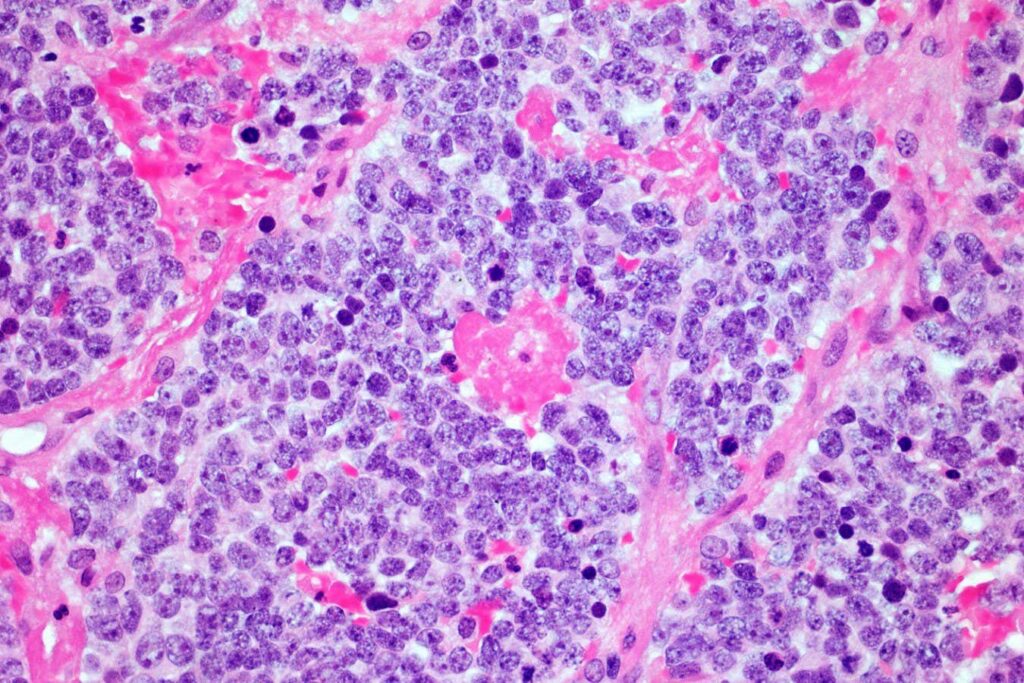

Microscopic images of neuroblastoma tumors

Simon Belcher/Aramie

Cancer therapy using genetically modified immune cells called CAR T cells has maintained people without potentially fatal neurotumors for a record 18 years.

“This is, to my knowledge, the longest lasting complete remission among patients who have received T-cell therapy in their car,” he says. Karin Stratoff At University College London, where he was not involved in treatment. “This patient will be cured,” she says.

Doctors use CAR T-cell therapy to treat certain blood cancers, such as leukemia. To do this, they collect samples of T cells that form part of the immune system from the patient's blood and genetically manipulate them to target and kill cancer cells. The modified cells are then returned to the body. In 2022, a follow-up study found that this approach was in remission for two people with leukemia for about 11 years.

However, CAR T-cell therapy usually fails against solid tumors such as neuroblastoma. Neuroblastoma occurs when developing neurons in children and usually becomes cancerous before the age of five. Such tumors often resist being attacked by the immune system, reducing the effectiveness of the modified T-cell.

This is the reason Cliona Rooney At Baylor School of Medicine in Houston, Texas, and her colleagues were surprised that people with neuroblastoma in childhood treated with CAR T cell therapy as part of their 2005 trial remained in control of cancer. . 18 years later. “These results were amazing. It's very rare to get a complete response from neuroblastoma with this approach,” says Rooney.

The person was treated at age 4 after several chemotherapy and radiation therapy failed to completely eradicate the cancer. At the time, the team also treated 10 other people who were in the same condition that the cancer had recurred after standard treatment, and they all had virtually no side effects, says Rooney. One of these participants showed no signs of cancer before dropping out of the study nearly nine years later, making follow-up impossible. The remaining nine participants eventually died from cancer. This was mainly killed within a few years of receiving treatment.

It is unclear why some people responded much better than others. “That's a million dollar question. I really don't know why,” Rooney says.

One reason is that each individual's T-cell behaves slightly differently depending on a variety of lifestyle factors, such as their genetics, prior exposure to infections, and diet, Rooney says. In fact, the team found that CAR T cells last longer in the blood among longer surviving participants.

Another explanation is that some participants' tumors were more immunosuppressive and strongly resisted T cells in the car, Rooney says.

The Rooney team is now looking for new ways to design cells so that it can benefit more people. “We have to improve them and make them stronger without increasing toxicity,” she says.

Such efforts are likely to lead to even greater success, Straathof says. “Now we have a glimpse of what is possible.”

topic:

Source: www.newscientist.com