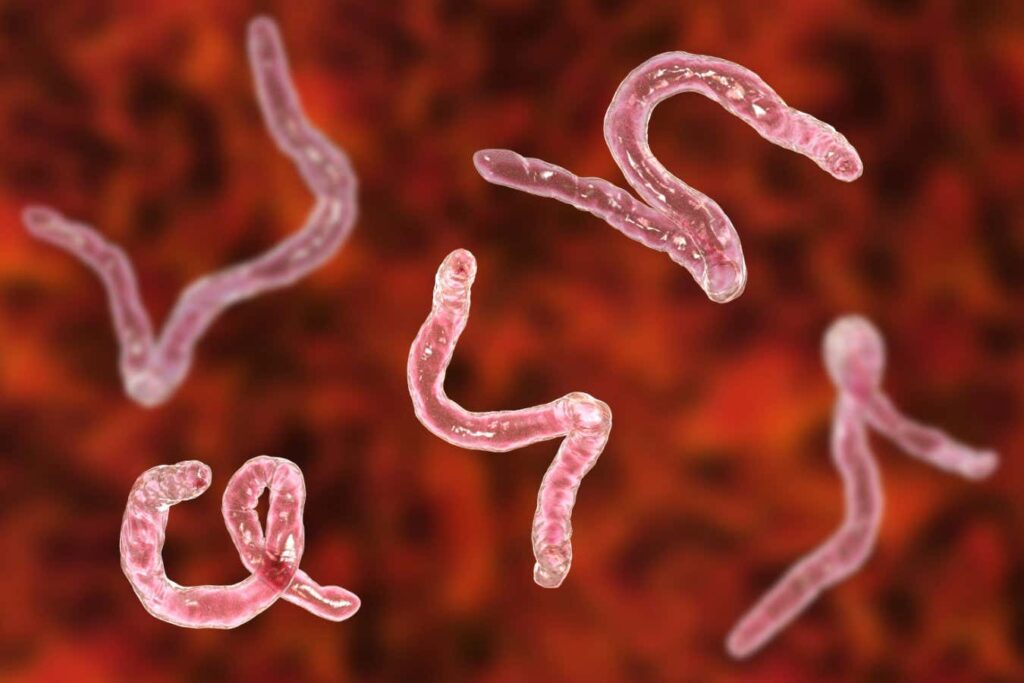

Duodenal hookworms (Ancylostoma duodenale) cause one of the most common intestinal parasitic infections worldwide.

Katerina Conn/Shutterstock

People with intestinal parasitic infections, quarter This has been suggested by experiments in mice infected with the parasite, which had significantly weaker immunity after receiving a COVID-19 vaccination compared to mice not infected with the parasite.

Previous studies have shown that people with intestinal parasitic infections have a weakened immune response to vaccines for diseases such as tuberculosis and measles because the parasites suppress the processes that vaccines trigger to confer immunity, such as activating pathogen-killing cells. Intestinal parasitic infections are most common in tropical and subtropical regions, where they often occur because of limited access to clean water and sanitation.

Scientists have not tested whether these pathogens reduce the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines. Michael Diamond Researchers at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, vaccinated 16 mice with a COVID-19 mRNA vaccine, half of which had been infected 12 days earlier with an intestinal parasite that lives only in rodents. They gave each mouse a booster shot three weeks after the first vaccination.

About two weeks after the booster shot, the researchers analyzed the animals' spleens to measure concentrations of CD8+ T cells, specialized white blood cells that are important for eliminating other cells infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus. They found that the spleens of mice infected with the intestinal parasite had about half the number of cells as mice without the parasite, suggesting a weakened immune response to the vaccine.

The researchers repeated the vaccination process in another group of 20 mice, half of which were infected with the intestinal parasite, exposing them to the highly infectious Omicron variant of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. After five days, the lungs of vaccinated rodents infected with the intestinal parasite had, on average, about 20% more virus than uninfected ones.

These findings suggest that intestinal parasites may reduce the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in people, but different types of intestinal parasites are known to affect immunity differently, the researchers say. Keke Fairfax The University of Utah researchers said it's unclear whether the parasite's infection in humans would have the same effect on vaccinating against COVID-19 as it did in mice, and the situation is further complicated by the fact that humans tend to harbor multiple types of intestinal parasites at the same time, they said.

Still, understanding how to alter the immune response to vaccination is important given the prevalence of parasitic infections, and these findings suggest that researchers may need to further evaluate the vaccine's effectiveness in parts of the world where a high proportion of the population is infected with intestinal parasites, Fairfax says.

topic:

Source: www.newscientist.com