“Humanity exists on a scale intermediate between elementary particles and the observable universe.” Milky Way Galaxy.

Shutterstock/Nednapa

When measured by orders of magnitude, it is sometimes argued that humanity lies somewhere between subatomic particles and the observable universe. (Put another way, we are somewhere between nothing and everything.) Whether or not this claim is strictly true, it commands attention and sympathy in all kinds of ways. I call. Each of our lives may feel like a whole universe, extremely important and infinite in scope, but from another perspective, each life is completely insignificant and fleeting. This is an impossible paradox, and this state of both surplus and surplus of value presents creative and moral opportunities. I love how these opportunities are explored in fiction, how scale makes human life, and indeed all life, unfamiliar, the infinite nature of its expanse, and I'm interested in what it can do to remind us of the improbability and wonder of its existence.

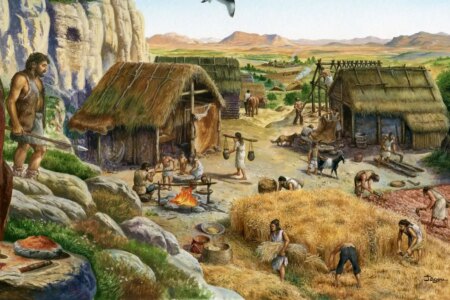

In each of my novels, especially At Ascension, I placed non-intuitive spatial and temporal perspectives next to the characters' more mundane concerns. Telescopes and microscopes explore deep time, evolution, and the life cycles of parasites and viruses alike. In addition to this, the characters eat, pace between rooms, have anxious, circular thoughts, worry about their families, and are bored. The lens zooms in and out from “domestic” to “foreign” scenes. I am not doing this to ridicule or belittle my characters, but rather that we are both infinite and infinitesimal, equal to the very big and the very small. I'm trying to evoke something in that paradoxical quality of closeness.

I've always been drawn to fiction that attempts this. When scenes with completely different perspectives collide, the effect is surprising, exhilarating and unforgettable. My favorite example is her 1927 novel by Virginia Woolf. To the lighthouse I first read it when I was a teenager. In the opening chapter, “The Window,'' page 134, Woolf gives us, through the character of Mrs. Ramsay, a consciousness so luminous that it seems impossible to define or limit it. In the next part, “Time Passes,” the perspective changes dramatically. The house is empty and the people have long left. Mrs. Ramsay, in her two short lines in parentheses, like an afterthought, we are informed that she has passed away.

I will never forget the shock and excitement I felt when I read this for the first time. I didn't know you could do something like this in fiction. Wolf's boldness and ambition took my breath away. She tragically demonstrated the power and danger of all her consciousness. This is a truism that cannot be repeated enough. Life feels endless, but it passes in the blink of an eye. Many of Woolf's novels are interested in this cacophony, as she lived through both world wars as well as the rapid advances in telescope power that changed all understanding of the size of the universe. This is no coincidence. And many believe that Woolf was not only an avid reader of astronomy books and his science fiction, but also that he had a lifelong commitment to writing that rivaled his most ambitious works. This seems obvious to people, but it's not surprising. SCIENCE FICTION.

main character of Ascension in progress, Lee Hasenbosch is a microbiologist who travels through deep space. Not only is she astonished to see the entire Earth, but she also experiences disappointment as she sees it disappear. Anthropocentrism – arguably the default perspective in English fiction – has never seemed so absurd. As she approaches the Oort Cloud, she becomes aware of other orders of life around her, ranging from algae food stocks to bacterial colonies that move between her and the rest of her crew. There is nothing beyond the ship's compound walls.

From an early age, Lee pursued the origins of life and became obsessed with the theory of life after an epiphany during a near-drowning experience. symbiosis And I was shocked at how impossible it was. It is almost impossible for life to exist, yet it is here. At the same time, she questions her own childhood and its influence on the person she became. Her life and work are centered around the pursuit of this ambiguous origin. So which scale is “correct”? Is she really interested in a universal story or a personal story? The answer, of course, is both. Neither answer alone is sufficient.

Martin McInnes Ascension in progress, published by Atlantic Books, is the New Scientist Book Club's latest pick.Register here and read along

topic:

Source: www.newscientist.com