A New Discovery: Gas Balls with Black Holes at Their Centers Shutterstock / Nazarii_Neshcherenskyi

The early universe is rich with enigmatic star-like gas balls powered by central black holes, a discovery that has astounded astronomers and may clarify some of the most significant mysteries unveiled by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

Upon initiating its observations of the universe’s first billion years, JWST uncovered compact, red galaxies that exhibited extraordinary brightness—galaxies unlike those found in our local universe. Previous interpretations suggested that these “small red dots” (LRDs) were either supermassive black holes engulfed in dust or densely packed star galaxies; however, these theories inadequately explained the light signals detected by JWST.

Recently, astronomers suggested that LRDs might actually be dense gas clusters with a black hole at their core, termed “black hole stars.” According to Anna de Graaf from Harvard University, as matter falls into a black hole, it emits immense gravitational energy, causing the surrounding gas to radiate light like stars. While this energy is distinct from nuclear fusion typical in stars, it results in a luminous mass of dense gas potentially billions of times brighter than our sun, according to de Graaf.

Despite some early evidence supporting this idea, a consensus remained elusive. Now, de Graaf and colleagues have reviewed the most extensive sample of LRDs since JWST’s launch, encompassing over 100 galaxies, and propose that these entities are best classified as black hole stars. “Although the term black hole star is still debated, there’s growing agreement within the scientific community that we’re observing accreting black holes enveloped by dense gas,” de Graaf noted.

When examining the spectrum of light emitted by an LRD, the observed patterns more closely resemble those from a uniform surface (blackbody) characteristic of stars, contrasting with the intricate and varied spectra from galaxies emitting light produced by a combination of stars, dust, gas, and central black holes.

“The black hole star concept has intrigued scientists for a while and, despite initial skepticism, is proving to be a viable explanation,” states Gillian Bellovary of the American Museum of Natural History. “Using a star-like model simplifies the framework for interpreting observations without necessitating extraordinary physics.”

In September, de Graaf’s team also identified another single LRD displaying a striking peak in the light frequency spectrum, which they dubbed “the cliff.” “We discovered spectral characteristics unexplainable by existing models,” de Graaf explained. “This pushes us to reevaluate our understanding and explore alternative theories.”

Presently, many astronomers agree that LRDs likely operate like vast star formations; however, de Graaf cautions that substantiating the black hole hypothesis presents challenges. “The core is hidden within a dense, optically thick envelope, obscuring what’s inside,” de Graaf explains. “Their brightness leads us to suspect they harbor black holes.”

A potential method to affirm their nature as black holes involves studying the temporal changes in emitted light, observing whether they fluctuate akin to known black holes in our universe, as noted by Western Hanki from Cambridge University. “We note brightness variances over brief intervals, yet there’s scant evidence of such variations in most LRD cases.”

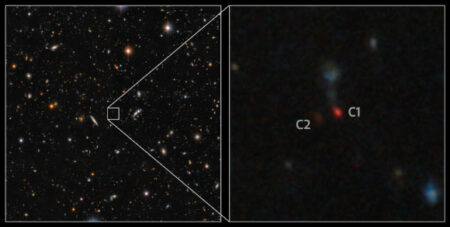

While JWST’s observational timeframe is limited, scrutinizing long-lived light fluctuations from LRDs may yield insights. A new study by Sun Fengwu and his team at Harvard recently uncovered a gravitational lens, an LRD that bends light around a massive galaxy between us and the object. This lens generated four distinct images of the original LRD, mimicking observations over 130 years and suggesting brightness variations similar to known pulsating stars, aligning with the hypothesis of black hole stars. Sun and his team opted not to comment for this article.

Although utilizing gravitational lenses to observe LRDs at different times is clever, Bellovary notes that other factors might account for brightness changes. “The data may not suffice to validate their conclusion. While I’m not dismissing their claims, I think there may be alternative explanations for the observed variations.”

If it turns out these galaxies are indeed black hole stars, de Graaf warns we’ll need to devise a new model addressing their origin and what they evolve into, given the absence of equivalent systems in our local universe. “This could represent a new growth phase for supermassive black holes,” she concludes. “The nature of these events and their significance to the final mass of black holes remains an open question.”

Join leading scientists for an exciting weekend dedicated to uncovering the universe’s mysteries, including a tour of the iconic Lovell Telescope. Topics:

Explore the Mysteries of the Universe in Cheshire, England

Source: www.newscientist.com