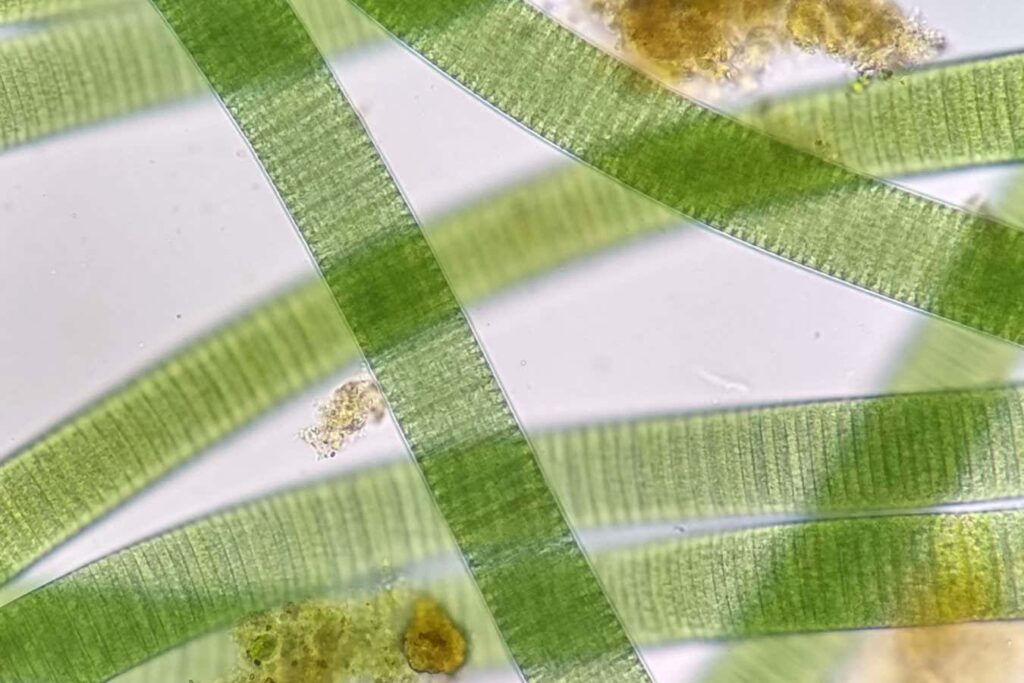

Microscopic image of a modern cyanobacterium called Oscillatoria

Shutterstock / Ekki Ilham

Researchers have identified photosynthetic structures inside a 1.75 billion-year-old cyanobacteria fossil. This discovery is the oldest evidence yet of these structures and provides clues to how photosynthesis evolved.

Emmanuel Javeau Researchers from the University of Liège in Belgium analyzed fossils collected from rocks at three locations. The oldest site is the approximately 1.75 billion-year-old McDermott Formation in Australia, the other two are the billion-year-old Grassy Bay Formation in Canada and the Bllc6 Formation in the Democratic Republic of Congo. was.

From these rocks, the researchers extracted fossilized cyanobacteria that produce energy through photosynthesis. “They're so small, less than a millimeter, that you can't see them with the eye,” Java says. She and her colleagues placed the fossils in resin, sliced them into sections 60 to 70 nanometers thick using a diamond-bladed knife, and analyzed their internal structures using an electron microscope.

They discovered that cyanobacteria in Australia and Canada contain thylakoids, membrane-enclosed sacs in which photosynthesis occurs. “These are the oldest fossilized thylakoids that we know of today,” Java says. Previously, the oldest thylakoid fossils were around 550 million years old. “So we delayed the fossil record by 1.2 billion years,” she says.

This is important because not all cyanobacteria have thylakoids and it is unclear when these structures, which make photosynthesis more efficient, first evolved, they said. Kevin Boyce at Stanford University in California. The origins of this diversification can now be traced back at least 1.75 billion years, he says. The oldest fossils of cyanobacteria are about 2 billion years old, but other evidence, such as geochemical signatures, indicate that photosynthesis has been around even longer than that.

It is widely believed that cyanobacteria helped build up oxygen in Earth's atmosphere 2.4 billion years ago. “The idea is that perhaps during this time they invented thylakoids, which increased the amount of oxygen on Earth,” Java says. “Now that we have discovered very old thylakoids and found them preserved in very old rocks, we think we might be able to test this hypothesis even further back in time,” she says. .

topic:

Source: www.newscientist.com