Today, the moon is a cold, dead world, but it hasn’t always been that way. Early in its history, the Moon was host to volcanic activity.

Now, the latest results from the first-ever samples returned from the far side of the moon by China’s Chang’e 6 spacecraft reveal this volcanic activity. It may have happened more recently More than previously suspected. But what remains unclear is how these eruptions were able to continue for so long.

The moon is tidally locked to the Earth, meaning the same side is always facing us. Throughout human history, the dark ocean on the moon’s near side (known as Mare) has been clearly visible.

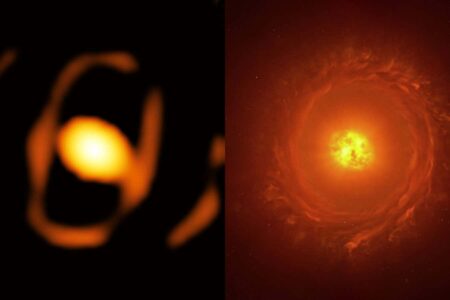

However, the far side of the Moon was hidden from our view and remained a mystery until the advent of the Space Age. In 1959, the Soviet Union’s Luna 3 satellite returned the first-ever images of the far side of the Moon, revealing a completely different surface than the familiar near side. There are only a handful of small oceans on the moon. Instead, much of the opposite side is pocked with impact craters.

Why do we know so little about the far side of the moon?

The Moon is dual-faced, and each side has a markedly different appearance. In recent years, experiments such as NASA’s GRAIL satellite have revealed that this dual personality extends underground as well.

“There is a dichotomy of the crust between the near and far sides, and the crust on the far side is much thicker,” he says. Professor Clive Neal a planetary geologist at the University of Notre Dame in the United States.

The cause of this split is one of the biggest unanswered questions about the moon. To get to the bottom of it, researchers first need to investigate what causes the two different appearances in the first place.

In the ’60s and ’70s, the Luna and Apollo missions returned vast amounts of lunar rock, confirming what geologists had long suspected: that the lunar maria was formed primarily from basalt (cooled lava). We were able to confirm that it is made of minerals.

The moon’s oceans were actually ancient volcanic floodplains that formed between 4.3 billion and 3.1 billion years ago. This conclusively proved that there was volcanic activity on the surface.

The absence of maria on the moon may suggest that there are no signs of volcanic activity on the far side, but a closer look at the craters on the far side shows that this may not be the case. Over time, the rocky world develops the patina of impact craters from meteorite impacts.

If the planet is volcanically active, lava flooding the surface will fill these craters and erase them from the surface. This means that the more craters there are on a planet’s surface, the longer it has been volcanic.

Using orbital images of the moon’s surface, scientists have been able to count craters on the moon, and it appears that the far side of the moon has actually been carved clean by volcanic activity on roughly the same time scale as seen on the near side. I discovered that it looks like.

So what did the new mission find?

The only way to confirm this theory was to test for volcanic minerals on samples from the backside. Unfortunately, all early lunar exploration aimed at the easiest place to land: the brightly lit equator in front of the moon.

Things changed on June 1, 2024, when China’s Chang’e 6 lander touched down on the far side of an area known as the Antarctic Aitken Impact Basin. This was China’s second venture into the far side, after landing a spacecraft in 2019. Chang’e 6’s main purpose was to bring samples of the far side back to Earth, ultimately revealing how geologically different this region is from the far side. .

Immediately after landing, Chang’e 6 scooped up some of the moon’s soil, known as regolith. They also used a 2-meter (6.5-foot) long drill to collect samples from underground, where moon rocks are somewhat protected from the sun’s radiation.

In all, the mission collected 1,935 g (4.2 pounds) of lunar material, which was packaged into an ascent vehicle and returned to Earth on June 6.

The return capsule was immediately taken to a special facility, where it was opened and subjected to preliminary tests, which revealed that the sample contained grains of basalt, proving that there was indeed a volcanic past behind it. It was done.

To learn more about what this past was like, more than 100 basalt fragments were extracted and sent to two independent teams of researchers who published their findings. science and nature November of this year.

They found that the basalt is about 2.8 billion years old, younger than the samples collected by Luna and Apollo.

How volcanic activity became possible is a “mystery”

The new sample matched a similarly young sample taken by China’s previous sample return mission, Chang’e 5.

Neither sample contained a group of metals called KREEP (potassium, rare earth metals, and phosphorus with the element symbol K) that were abundant in the previous samples. There was also a clear shortage of radioactive metals. Also a sample of Chang’e.

“The mystery is that young basalts, less than 3 billion years old, do not contain large amounts of KREEP radioactive elements either in the foreground or in the background,” said one of the few Western scientists allowed to cooperate in this research. Mr. Neil, one of the Analysis at this time.

“This is a mystery, but it matches the young basalt of Chang’e 5, which is 2 billion years old.”

Heat from the decay of radioactive metals is one of the main mechanisms that sustains volcanic activity on our planet, but their apparent disappearance does not seem to have immediately stopped volcanic activity on the Moon. As it turns out, the samples are very similar in many other ways.

“They are similar in bulk composition to previous samples, which adds to the mystery: What was the heat source that produced such magmas?” says Neal.

Getting to the bottom of the mystery will almost certainly require more samples taken from different parts of the moon, as well as a closer look at what’s happening beneath the surface.

“The absence of creep elements in the basalts on the far side suggests that the Moon’s mantle is also bipartite. To understand the nature of the Moon’s interior, we need to use global geophysical networks to You need to explore what’s inside.”

It appears the other side still wants to keep some of its secrets hidden, at least for now.

About our experts

Professor Clive Neil is an expert in civil and environmental engineering and geosciences at the University of Notre Dame in the United States. His research is natural earth science, science and advances in space research.

read more

Source: www.sciencefocus.com