Approximately 500,000 stars illuminate this section of the Milky Way galaxy

NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, and S. Crowe (University of Virginia).

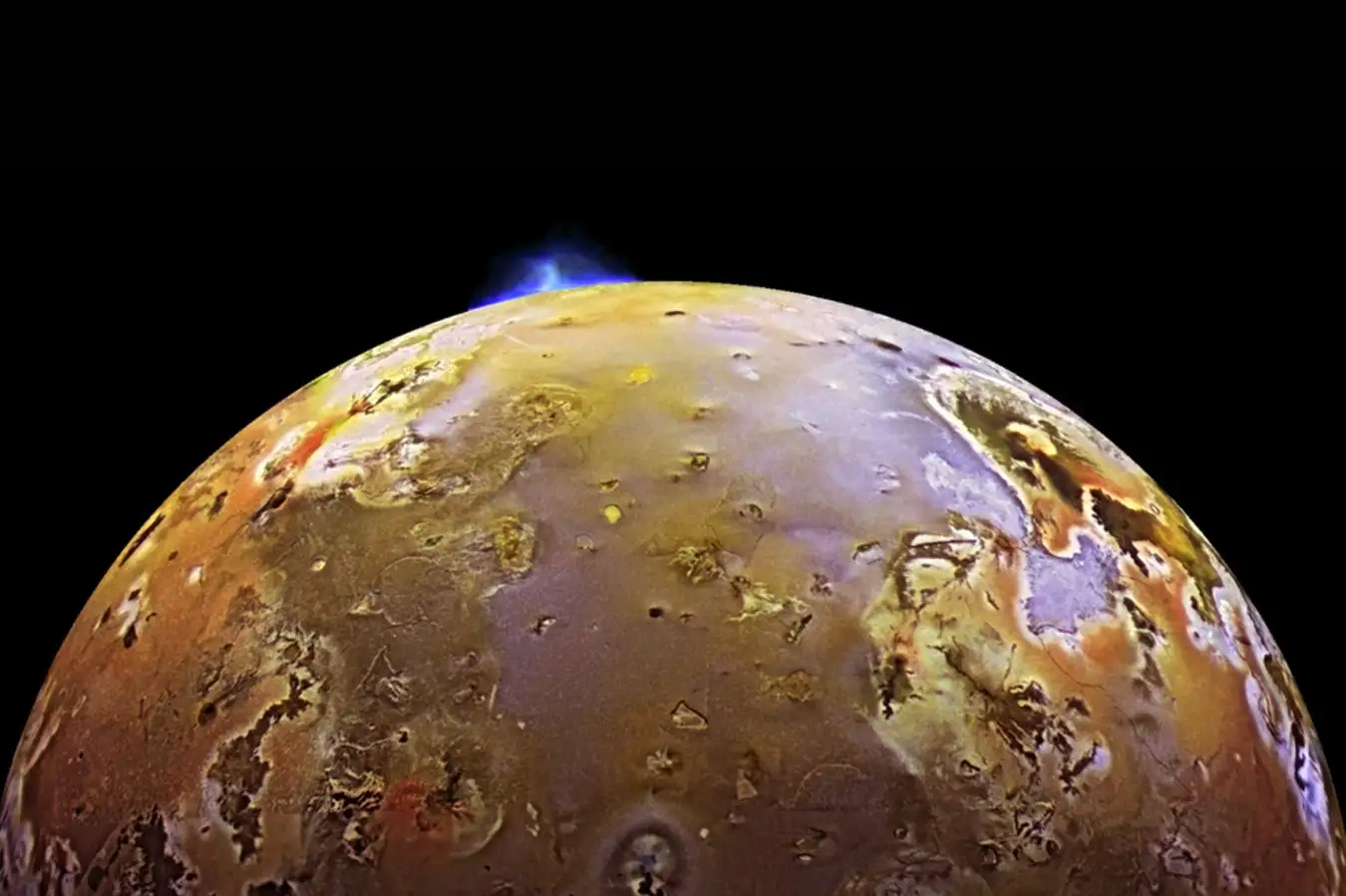

One significant challenge in discussing space and spacetime is the difficulty in grasping the vastness of the universe. It can be a struggle just to comprehend the scale of our solar system. For instance, if we model the Earth as being 1 centimeter in diameter, Pluto would need to be positioned 42 meters away! This distance is far greater than most homes can accommodate.

However, our solar system is quite small when compared to the scale of the Milky Way. Beyond the fact that our galaxy resides within an unseen halo of dark matter that extends far beyond what we can see, the Milky Way itself is immense; it would take about 100,000 years to traverse its entirety. In contrast, light travels from the Sun to Pluto in only 5.5 hours.

Notably, I’ve transitioned from daily distance measures to units related to the speed of light—they represent about 100,000 light-years, equivalent to 9.46 x 1020 meters. How can one visualize such vastness? It might be akin to comparing it to the scale of a ballroom. And the Milky Way is diminutive compared to the entire universe; it’s not even considered a particularly large galaxy, especially with our neighboring Andromeda being twice its width.

Moreover, spacetime is continuously expanding. This expansion doesn’t influence distance measurements within gravity-bound regions like our solar system or the Milky Way, nor does it impact the distances between galaxies. The Milky Way and Andromeda are actually moving towards one another, but the eventual collision will resemble a gentle dance rather than a catastrophic crash—at least 4.5 billion years are still required before this occurs!

However, on a grander scale, spacetime extends, causing clusters of galaxies to drift apart. This phenomenon is known as the Hubble expansion and implies that many measurements of spatial distance are subject to change. Billions of years down the line, future observers will have different calculations due to the expanding gap between us and the Virgo galaxy cluster.

Typically, these figures inspire awe, but they inevitably invite skepticism. A common question is how we ascertain these measurements. The answer lies in a “ladder” of measurements that astronomers use. Often, distances can be determined through objects with known brightness, such as certain types of stars.

Why don’t distant galaxies appear blurry, considering the expansion of space-time?

The simplest method employs Cepheid variable stars, which pulsate periodically, to calculate distances. These stars are effective over a specific range, after which another method is needed. Over the past three decades, astronomers have relied on specific types of supernovae, as they understand how their light behaves during the expansion of space-time. Other techniques also exist, like measuring the properties of bright red giant stars.

We possess a high level of confidence in our ability to measure long distances. However, we recognize why some readers raise questions about this process. One inquiry pertains to what happens to light as the universe expands. The standard view in cosmology is that, as space-time expands, light waves stretch, leading to a redshift much like how the frequency of a siren decreases. As previously noted, measuring this redshift is crucial for using supernovas to calculate distances.

Redshift indicates that light has lower energy than it did previously. However, there’s no apparent place for this “lost” energy to go, raising doubts. In Newtonian physics, energy must be accounted for, but this isn’t necessary in general relativity. In essence, the mechanisms that enable us to measure vast distances contradict our everyday understanding of how energy behaves in the universe.

Another related question from readers involves images of distant galaxies, like the first photo from the new Vera C. Rubin Observatory. Shouldn’t galaxies appear blurry due to the expansion of space-time?

It’s important to clarify that “observing” the expansion of space-time isn’t like watching an F1 race. It’s more akin to viewing an F1 race that unfolds over billions of years; the vast distances make the galaxies appear practically stationary. The only indicators we have of their separation are measurements like redshift, which simply track how light stretches over distances—not real-time observations of a galaxy’s motion.

I genuinely enjoy these types of questions as they delve into the nuances of how science communicators engage with their audiences. I appreciate that New Scientist readers challenge these metaphors to their limits!

Chanda’s Week

What I’m reading

A lot about the reasons behind its popularity—The Adventures of Alice in Wonderland.

What I’m seeing

I finally enjoyed viewing Station Eleven.

What I’m working on

I’ve been pondering a lot about the true nature of quantum fields. Curious!

Chanda Prescod-Weinstein is an associate professor of physics and astronomy as well as a core faculty member within women’s studies at the University of New Hampshire. Her latest book is titled “The Disturbed Cosmos: A Journey to Dark Matter, Space, and Dreams.”

Topic:

Source: www.newscientist.com