In 1957, the first man-made object was successfully launched into space and into orbit around the Earth. This was Sputnik 1, a beautifully simple Soviet spherical satellite with only four antennae.

But this historic event also marked the beginning of another, more disturbing one. It means that humans left the first space debris in orbit around the Earth.

Part of the 267-ton, 30-meter-tall rocket that launched Sputnik also became stuck in orbit. Suddenly, the world was faced with a problem we didn’t know we needed to solve: outer space littering.

Thankfully, Sputnik and the rocket debris it left behind deorbited shortly after launch and burned up in the atmosphere. However, this was not always the case. Just 66 years of space exploration has left vast amounts of detritus in orbit around Earth.

Now, NASA and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) are considering ideas to help solve this problem. The idea is to build a satellite out of wood, a widely available biodegradable material.

Space junk is currently a problem

The problems that government agencies are trying to address are big and complex, and they need to know how big the first phase of the project was. At least 130 million pieces of man-made debris are known to be orbiting the Earth, most of them flying at speeds of more than 7 kilometers per second. This is eight times faster than a normal bullet. But while this is a staggering number, some scientists believe it is a conservative estimate.

Most objects sent into space remain in space until either they deorbit and burn up on re-entry, or they are pulled away from Earth into graveyard orbits, where they orbit for hundreds of years. The majority of such objects are actually very small, less than 1 cm in diameter, from paint chips to small pieces of electronic equipment to pieces of insulation foam and aluminum.

Such tiny pieces cannot be seen from Earth, even with powerful telescopes. Therefore, we need to look for evidence left behind when it collides with other objects in space. This is no easy task.

Work to assess the scope of the problem began in earnest after five extraordinary objects, the NASA Space Shuttles, repeatedly orbited and returned. Since 1981, NASA has launched a total of 135 shuttle missions.

After each shuttle returned to Earth, it was evaluated using a fine-tooth comb to identify damage caused by orbital debris. This gives NASA a clearer picture of the problem of small pieces of dead satellites flying through space.

read more:

NASA scientists have discovered exactly what they expected: small pieces of debris just a few millimeters in diameter can cause small but powerful impacts. NASA also produced the first estimates of how degraded the debris environment is.

Prior to 1978, NASA scientists Don Kessler and Barton Coolpare had proposed a scenario they named Kessler syndrome. The phenomenon they discussed is a catastrophic event in which when a satellite is shattered by space debris, the resulting debris destroys more satellites, creating even more debris, repeating an endless chain of events. It is a chain of

Obviously, this is a big problem. So how can we slow down the rate of debris formation or eliminate it altogether? Proposed solutions include using radiation hardening to reach space within five years of launch. It involves taking the ship out of orbit.

materials (designed to be less susceptible to damage from exposure to the high levels of radiation and extreme temperatures experienced in space) and launches on reusable rockets.

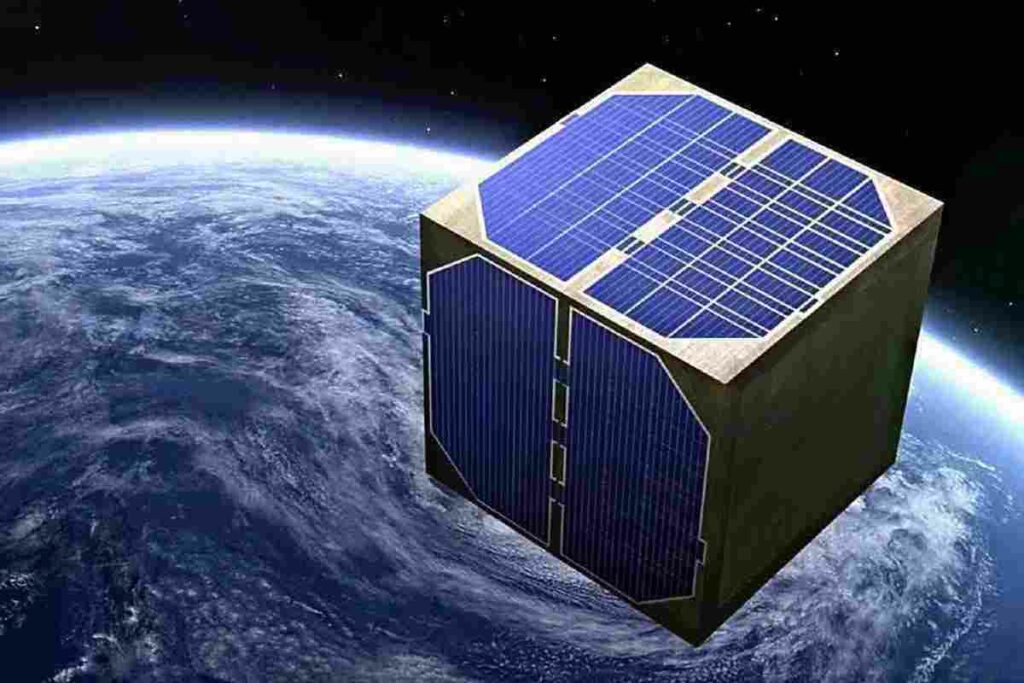

Incorporate the idea of a wooden satellite. LignoSat, the name of the NASA and JAXA project, is a coffee machine built using traditional Japanese joinery techniques that houses electronics and other materials needed for space missions, much like today's CubeSats. It is a cup-sized (approximately 10x10x10cm) wooden box.

Wood samples were tested for suitability over 290 days in 2022 on the International Space Station's Kibo Japanese Experiment Module.

Magnolia coped well and performed best when exposed to intense cosmic rays and extreme temperature changes in its harsh environment. It does not burn, rot, crack, or deform, and has the important property that upon re-entry into the atmosphere, it burns up to a fine ash, leaving behind small fragments.

Another advantage of wooden satellites is their reflectivity, or rather their lack of reflectivity. Currently, reflections from aluminum satellites are so bright that they can be easily spotted from Earth with the naked eye. Importantly, this reflected light can reach sensitive areas and interfere with astronomical observations.

LignoSat test launch is currently scheduled for 2024. Success could pave the way for further missions.

So will all satellites be made of wood in the near future? Unfortunately, that is unlikely. On the plus side, projects like this encourage researchers to think outside the box and can have a greater impact in the future. If LignoSat is successful, more research groups may try to introduce biodegradable materials to reduce further debris generation.

But for now, I strongly support efforts to actively track as many objects in Earth orbit as possible to reduce future collisions with matter in space.

read more:

Source: www.sciencefocus.com