In a newly published paper in this month’s iScience, researchers from the University of Tübingen and their collaborators present an interdisciplinary study of ancient stone and bone projectile points associated with Homo sapiens from the Lower Paleolithic era (40,000 to 35,000 years ago). This comprehensive research uses a blend of experimental ballistics, detailed measurements, and use-wear analysis, revealing that some of these prehistoric artifacts correspond not just to hand-thrown spears and javelin darts but also potentially to bow-propelled arrows.

Evidence suggests early humans may have used bows, arrows, and spear throwers in the Upper Paleolithic period. Image credit: sjs.org / CC BY-SA 3.0.

For decades, it was commonly believed that weapon technology evolved linearly, transitioning from hand-held spears to spear-throwing and eventually to bows and arrows.

However, lead researcher Keiko Kitagawa and her team at the University of Tübingen challenge this notion, arguing for a more complex evolution of weapon technology.

“Direct evidence of hunting weapons is rarely identified in the archaeological record,” they noted.

“Prehistoric hunting weapons encompassed a range from hand-held thrusting spears ideal for close-range hunting, to javelins and bow-headed arrows suitable for medium to long-range engagements.”

“The earliest known instances of such tools include wooden spears and throwing sticks, dating back 337,000 to 300,000 years in Europe.”

“Spear-throwing hooks first appeared during the Upper Solutrean period (around 24,500 to 21,000 years ago), gaining prominence in the Magdalenian culture of southwestern France (approximately 21,000 years ago), with nearly 100 specimens documented.”

Bows and arrows, however, have only surfaced from well-preserved sites like Mannheim-Vogelstang and Stermol in Germany, dated to about 12,000 years, and Lilla Roschulz-Mosse in Sweden, approximately 8,500 years, indicating they are significantly younger than other projectile technology.

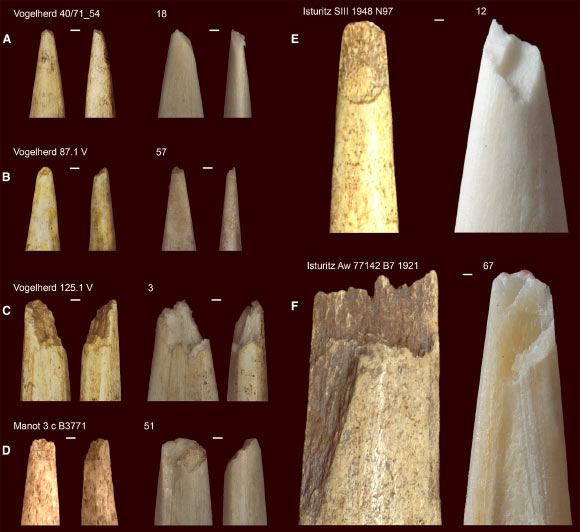

Comparison of archaeological specimens from the Aurignac site with experimental examples from Vogelherd, Istritz, and Manot. Image credit: Kitagawa et al., doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2025.114270.

The authors propose that early modern humans may have concurrently experimented with various projectile technologies, adapting to diverse ecosystems and prey types.

The analysis reveals that the damage patterns on these ancient projectile points corresponded with what is expected from arrows shot from bows, as well as from spears and darts.

“We emphasize Upper Paleolithic bony projectiles, including split bases and megabases made from antler and bone, predominantly discovered in Aurignacian environments in Europe and the Levant, between 40,000 and 33,000 years ago,” the researchers explained.

“Our goal is to determine if the wear patterns and morphometry can identify the types of weapons associated with Aurignacian bone projectile tips.”

This discovery aligns with previous archaeological findings indicating that bows and arrows were utilized in Africa as far back as 54,000 years ago, predating earlier estimates and some of Europe’s archaeological record.

Importantly, the researchers do not assert that Homo sapiens invented the bow simultaneously across all regions, nor do they claim the bow was the only weapon used.

Instead, their findings suggest a rich technological diversity during the initial phases of human migration into new territories.

“Our study highlights the intricate nature of reconstructing launch technologies, which are often made from perishable materials,” the researchers stated.

“While it is impossible to account for all variables affecting the properties of the armature and resulting wear, we aspire to implement future experimental programs aimed at deepening our understanding of the projectiles that form a crucial component of hunter-gatherer economies.”

_____

Keiko Kitagawa et al. suggest that Homo sapiens may have utilized bows and arrows for hunting as early as the Upper Paleolithic period in Eurasia. iScience published online on December 18, 2025. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2025.114270

Source: www.sci.news