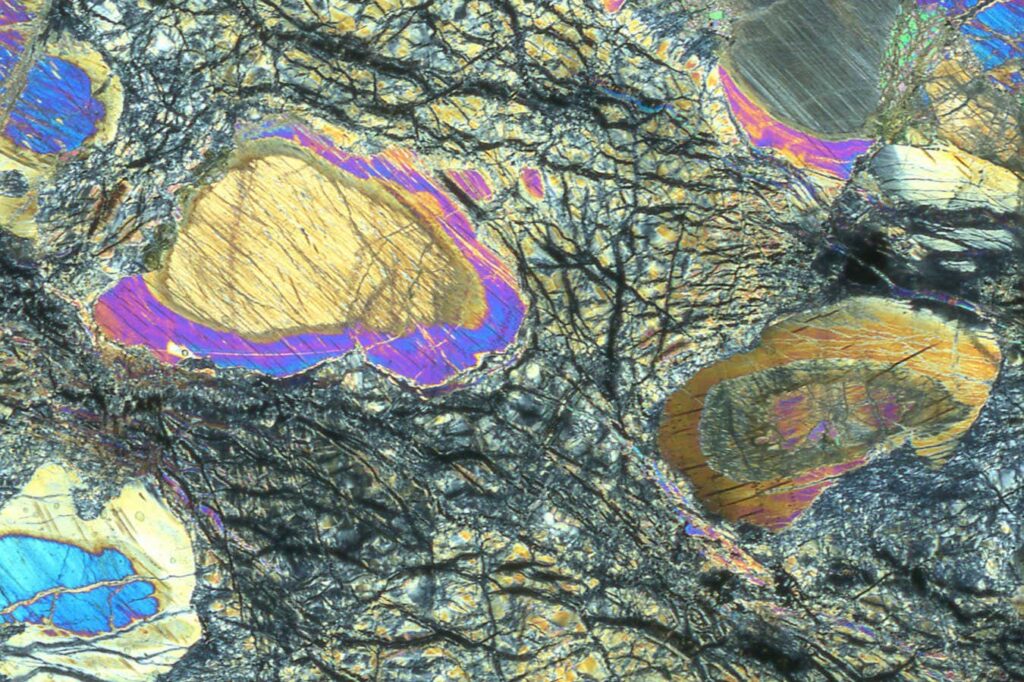

A rock sample from Earth’s mantle viewed under a microscope

Johan Lissenberg

In the middle of the North Atlantic, geologists have drilled 1,268 metres below the seafloor – the deepest hole ever drilled into Earth’s mantle – and analysis of the resulting rock core may provide new clues about the evolution of the planet’s outermost layers and even the origin of life.

The Earth is generally made up of several different layers, including the solid outer crust, the upper and lower mantle, and the core. The upper mantle, located just below the crust, is made up primarily of magnesium-rich rocks called peridotites. This layer drives important planetary processes such as earthquakes, the hydrological cycle, and the formation of volcanoes and mountain ranges.

“Until now, we’ve only been able to see fragments of the mantle,” Johan Lissenberg “However, there are many places on the seafloor where the mantle is exposed,” said researchers from Cardiff University in the UK.

One such region is an underwater mountain called Atlantis Mountains, located near a volcanically active area of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Pieces of the mantle constantly come to the surface and melt, giving rise to the region’s many volcanoes. Meanwhile, as seawater seeps deeper into the mantle, it is heated by higher temperatures, producing compounds such as methane, which bubbles up from hydrothermal vents and serves as fuel for microorganisms.

“There’s a kind of chemical kitchen beneath the Atlantis massif,” Lisenberg says.

To learn more about this dynamic region, he and his colleagues initially planned to use the drilling ship JOIDES Resolution to drill 200 meters into the mantle, deeper than researchers had gone before.

“We then started drilling and it went surprisingly well,” a team member said. Andrew McCaig “We retrieved a very long continuous fragment of rock and decided to go for it and go as deep as we could,” said researchers from the University of Leeds in the UK.

Ultimately, the team succeeded in drilling to a depth of 1,268 metres into the mantle.

When the researchers analyzed the drill core samples, they found that they had a much lower content of a mineral called pyroxene compared to other mantle samples from around the world, suggesting that this particular part of the mantle underwent significant melting in the past, depleting it of pyroxene, Lisenberg said.

In the future, he hopes to recreate this melting process, which will allow him to understand how the mantle melts and how that molten rock travels to the surface to feed oceanic volcanoes.

Some scientists believe life on Earth began deep in the ocean near hydrothermal vents, so by studying the chemicals that show up along the cylindrical rock cores, microbiologists hope to determine the conditions that may have led to the emergence of life, and at what depths below the ocean floor.

“This is a very important borehole because it will provide a reference point for scientists across many scientific disciplines,” McCaig says.

“While a one-dimensional sample from Earth cannot provide complete information about the three-dimensional migration paths of melt and water, it is still a major achievement,” he said. John Wheeler At the University of Liverpool, UK.

topic:

Source: www.newscientist.com