A groundbreaking study by a team of paleontologists from Mexico and the United States has unveiled a new species of bird-like dinosaur, Xenovenator Espinosai, notable for its exceptionally thick, dome-shaped skull. This unique adaptation suggests it may have engaged in headbutting behaviors during conflicts with its peers.

This newly identified dinosaur species thrived during the late Cretaceous period, approximately 73 million years ago.

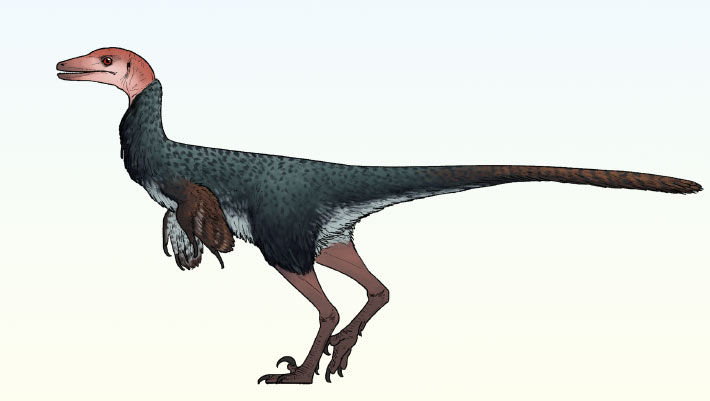

Xenovenator Espinosai is part of the Troodontidae family, which includes agile theropod dinosaurs closely related to modern birds.

The holotype and paratype specimens were uncovered during surface sampling in the Cerro del Pueblo Formation located in Coahuila state, northern Mexico, in the early 2000s.

While Troodontids are recognized for their larger brains and heightened sensory capabilities, this species distinguishes itself through an exceptionally thick skull roof.

The holotype specimen retains nearly the entire brain case, showcasing a strongly dome-shaped structure that reaches thicknesses of up to 1.2 cm.

CT scans reveal that the skull features a dense architecture with closely interlocked sutures and a rugged, textured exterior.

This structural resemblance to the reinforced skulls of dome-headed pachycephalosaurs highlights an evolutionary adaptation for intraspecific combat, particularly head-butting.

While display structures and combat weapons are common among many dinosaur species, detailed adaptations for fighting have yet to be recorded in non-avian maniraptoran theropods.

The paratype specimen of Xenovenator Espinosai shows less pronounced cranial thickening, which may indicate variability due to age or sex, suggesting that the most significant skull enhancements occurred later in development or were selective to one sex.

“The thickened, deformed skull of Xenovenator Espinosai is unparalleled among maniraptorans, with its precise function remaining unclear,” stated lead author Dr. Hector Rivera Silva from Museo del Desierto.

“Several traits that appear to serve no obvious survival advantage, such as cranial horns and crests, may be the result of sexual selection.”

“In contemporary mammals and birds, these attributes can be utilized for display or as weapons during courtship.”

“Considering our findings—skull thickening, cranial doming, and intricate sutures—it is likely that the domed skull of Xenovenator Espinosai was an adaptation for intraspecific combat,” they added.

This discovery marks the first documented case of a parabird exhibiting a specialized skull for combat among its species.

Interestingly, researchers noted that wrinkled frontal bones and similar features in the maxilla and nasal bones of troodontids may suggest widespread intraspecific fighting, with heightened intensity observed in Xenovenator Espinosai.

The phylogenetic analysis indicates that despite being part of a larger North American troodontid lineage, Xenovenator Espinosai’s distinctively thick, domed skull highlights its unique evolutionary niche within the group.

The recurrent evolution of intricate display features and weapons during the Cretaceous hints at the increasing importance of sexual selection in dinosaur evolution.

This finding enriches our understanding of the diversity among troodontid dinosaurs from southern Laramidia, offering rare insights into how even smaller, lighter theropods developed traits specialized for physical confrontation.

Researchers propose that related species like Xenovenator Robustus signify a distinct clade of heavily built troodontids endemic to the Southwest, emphasizing the uniqueness and diversity of southern Laramidian fauna.

“Sexual selection, encompassing adaptations for display and combat, was likely a pervasive phenomenon among dinosaurs during the Late Cretaceous period,” they concluded.

For further details on this discovery, refer to the research paper published in the journal Diversity.

_____

Hector E. Rivera-Silva et al. 2026. A troodontid theropod with a thick skull that lived in late Cretaceous Mexico. Diversity 18(1):38; doi: 10.3390/d18010038

Source: www.sci.news