Two extinct hominins, Australopithecus afarensis and Australopithecus africanus, exhibited much greater sexual dimorphism than chimpanzees and modern humans. According to Dr. Adam Gordon, a paleontologist at the University of Albany and Durham, Australopithecus afarensis displayed even higher levels of dimorphism.

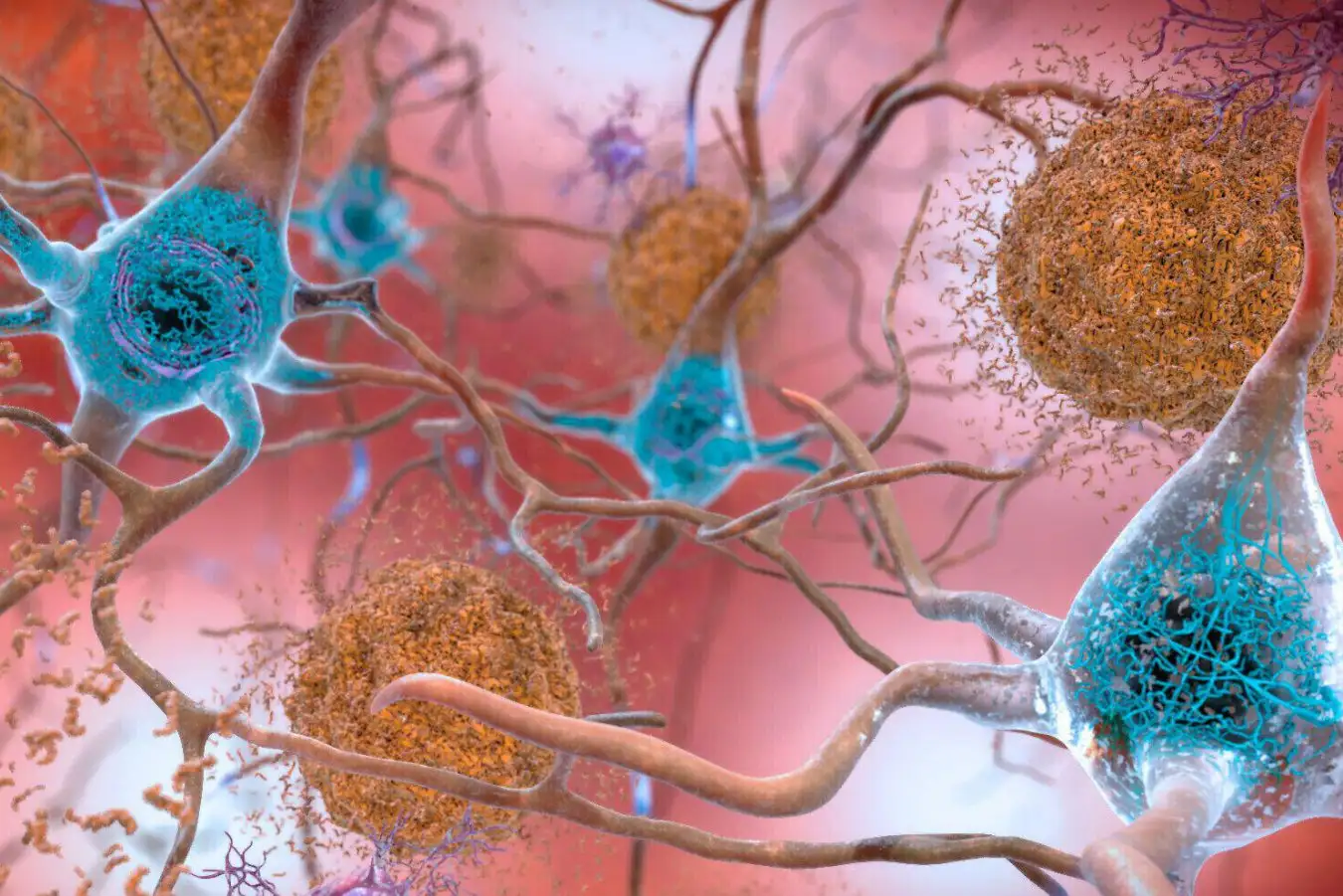

Reconstructing the face of Australopithecus afarensis. Image credit: Cicero Moraes/CC by-sa 3.0.

The sexual size dimorphism is not just a mere physical trait; it indicates deeper behavioral and evolutionary strategies.

In line with sexual selection theory, the sexual size dimorphism seen in modern primates typically correlates with intense male-male competition and social structures, fostering a one-sided mating system where one or more large males dominate access to multiple females.

Conversely, low sexual dimorphism is characteristic of species that exhibit paired social structures with lower competition for mating opportunities.

Contemporary human populations show low to moderate sexual size dimorphism, with males generally being slightly larger than females on average, although there is considerable overlap between the sexes.

Fossil data is often incomplete, making it exceedingly difficult to ascertain the gender of ancient individuals.

To overcome this issue, Dr. Gordon utilized a geometric averaging method for estimating size from multiple skeletal elements, including the upper arm, femur, and tibia.

Resampling techniques were then employed to simulate thousands of comparisons between fossil hominins and living primates, ensuring that the statistical model accounted for the incomplete and varied nature of fossil samples.

A comparative framework was developed using data from contemporary gorillas, chimpanzees, and humans with known genders and complete skeletons.

Unlike earlier studies where ambiguous or inconclusive statistical results were interpreted as signs of similarity, Dr. Gordon’s approach unveiled clear and significant differences, even with relatively small fossil samples.

To eliminate the potential of body size changes in Australopithecus afarensis reflecting broader evolutionary trends rather than gender distinctions, Dr. Gordon also analyzed time series trends over a 300,000-year span from the Khadar Formation in Ethiopia.

His analysis indicated no significant size increase or decrease over time, suggesting that the observed variations were more likely due to differences between males and females.

“These were not minor differences,” Dr. Gordon stated.

“In the case of Australopithecus afarensis, males were significantly larger than females—possibly more so than the great living apes.”

“Both of these extinct hominin species displayed gender-specific size distinctions from modern humans, yet differed from extant ape species in this regard.”

Australopithecus africanus. Image credit: JM salas/cc by-sa 3.0.

Dr. Gordon’s previous research indicates that the elevated sexual size dimorphism seen in living primates may correlate with considerable resource stress. In situations where food is scarce, smaller, healthier females can better meet their metabolic needs and reproduce quicker than larger females, leading to offspring with smaller mothers and greater size disparities between males and females.

The pronounced sexual size dimorphism observed in both Australopithecus afarensis and Australopithecus africanus suggests a high level of male competition, akin to differences noted in chimpanzees and gorillas. However, the distinctions between the two fossil species could reflect varying intensities of sexual selection or resource stress in their environments (e.g., differences in the length of dry seasons that could affect female body size).

In any event, the high sexual size dimorphism of these fossil hominins starkly contrasts with the more balanced sizes seen in modern humans, offering insights into different models of early human existence.

The implications of these findings are significant. Australopithecus afarensis, which inhabited the Earth between 3.9 and 2.9 million years ago, is often viewed as very closely related to the direct ancestors of modern humans.

However, its pronounced sexual dimorphism suggests that early human social systems may have been much more hierarchical and competitive than previously believed.

On the contrary, Australopithecus africanus—which appears slightly later in the fossil record—exhibits less dimorphism compared to Australopithecus afarensis. This could represent different evolutionary branches within the human lineage or perhaps reflect various social behavioral stages in the development of hominins.

“We often categorize these early hominins together as a single group called Gracile Australopithecines, believed to have interacted with their physical and social environments in similar ways,” Dr. Gordon explained.

“While there is some truth to this, the significant differences in dimorphism between the two species indicate that these closely related hominins were under distinct selection pressures, unlike those affecting modern human pair bonds.”

The survey findings will be published in the American Journal of Biological Anthropology.

____

Adam D. Gordon. 2025. Dimorphism of sexual size in Australopithecus africanus and A. afarensis in contrast to modern humans despite low power resampling analysis. American Journal of Biological Anthropology 187(3): E70093; doi: 10.1002/ajpa.70093

Source: www.sci.news