A significant enigma in vertebrate evolution—why numerous major fish lineages appeared suddenly in the fossil record tens of millions of years post their presumed origins—has been linked to the Late Ordovician mass extinction (LOME). This insight comes from a recent analysis conducted by paleontologists at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University. The study reveals that the LOME, occurring approximately 445 to 443 million years ago, instigated a parallel endemic radiation of jawed and jawless vertebrates (gnathostomes) within isolated refugia, ultimately reshaping the early narrative of fishes and their relatives.

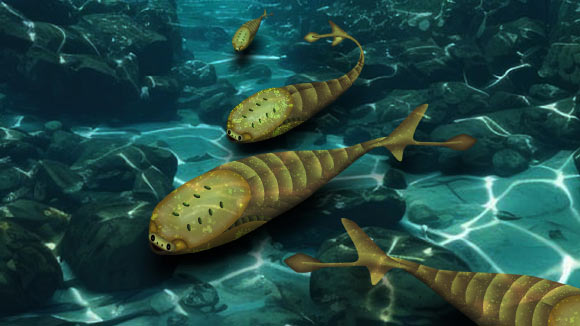

Reconstruction of Sacabambaspis jamvieri, an armored jawless fish from the Ordovician period. Image credit: OIST Kaori Seragaki

Most vertebrate lineages initially documented in the mid-Paleozoic emerged significantly after the Cambrian origin and Ordovician invertebrate biodiversity. This temporal gap is often attributed to inadequate sampling and lengthy ghost lineages.

However, paleontologists Kazuhei Hagiwara and Lauren Saran from the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University propose that the LOME may have fundamentally transformed the vertebrate ecosystem.

Utilizing a newly compiled global database of Paleozoic vertebrate occurrences, biogeography, and ecosystems, they identified that this mass extinction coincided with the extinction of stylostome conodonts (extinct marine jawless vertebrates) and the decline of early gnathostomes and pelagic invertebrates.

In the aftermath, the post-extinction ecosystems witnessed the initial definitive emergence of most major vertebrate lineages characteristic of the Paleozoic ‘Age of Fish’.

“While the ultimate cause of LOME remains unclear, clear changes before and after the event are evident through the fossil record,” stated Professor Saran.

“We have assimilated 200 years of Late Ordovician and Early Silurian paleontology and created a novel database of fossil records that will assist in reconstructing the refugia ecosystem,” Dr. Hagiwara elaborated.

“This enables us to quantify genus-level diversity from this era and illustrate how LOME directly contributed to a significant increase in gnathostome biodiversity.”

LOME transpired in two pulses during a period marked by global temperature fluctuations, alterations in ocean chemistry—including essential trace elements—sudden polar glaciation, and fluctuations in sea levels.

These transformations severely impacted marine ecosystems, creating post-extinction ‘gaps’ with reduced biodiversity that extended until the early Silurian period.

The researchers confirmed a previously suggested gap in vertebrate diversity known as the Thalimar gap.

Throughout this time, terrestrial richness remained low, and the surviving fauna consisted largely of isolated microfossils.

The recovery was gradual, with the Silurian period encompassing a 23-million-year recovery phase during which vertebrate lineages diversified intermittently.

Silurian gnathostome lineages displayed gradual diversification during an early phase when global biodiversity was notably low.

Early jawed vertebrates appear to have evolved in isolation rather than rapidly dispersing into ancient oceans.

The researchers noted that gnathostomes exhibited high levels of endemism from the outset of the Silurian period, with diversification occurring primarily in certain long-term extinction reserves.

One such refuge is southern China, where the earliest conclusive evidence of jaws is present in the fossil record.

These primitive jawed vertebrates remained geographically restricted for millions of years.

Turnover and recovery following LOME paralleled climatic fluctuations similar to those at the end of the Devonian mass extinction, including prolonged epochs of low diversity and delayed dominance of jawed fishes.

“For the first time, we discovered the entire body fossil of a jawed fish directly related to modern sharks in what is now southern China,” Dr. Hagiwara noted.

“They remained concentrated in these stable refugia for millions of years until they evolved the capability to migrate across open oceans to new ecosystems.”

“By integrating location, morphology, ecology, and biodiversity, we can finally understand how early vertebrate ecosystems restructured themselves after significant environmental disruptions,” Professor Saran added.

“This study elucidates why jaws evolved, why jawed vertebrates ultimately became widespread, and how modern marine life originated from these survivors rather than earlier forms like conodonts and trilobites.”

For more information, refer to the study published on January 9th in Scientific Progress.

_____

Kazuhei Hagiwara & Lauren Saran. 2026. The mass extinction that initiated the irradiation of jawed vertebrates and their jawless relatives (gnathostomes). Scientific Progress 12(2); doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aeb2297

Source: www.sci.news