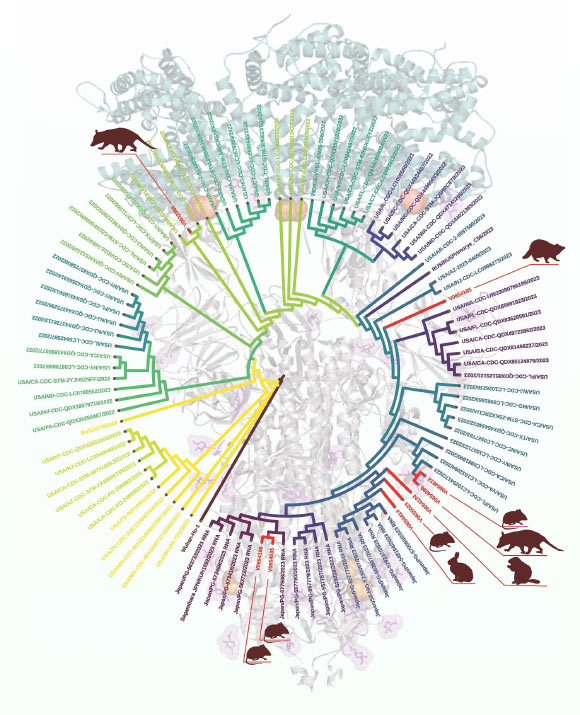

In a new study, a team of scientists from Virginia Tech investigated the extent to which exposure to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the causative agent of COVID-19, was widespread in wildlife communities in Virginia and Washington, DC, between May 2022 and September 2023. They documented positive detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in six species: deer mice, Virginia opossums, raccoons, groundhogs, cotton-tailed bats, and eastern red bats. They also found no evidence that the SARS-CoV-2 virus was transmitted from animals to humans, and people should not fear general contact with wildlife.

Goldberg othersThis suggests that a wide variety of mammal species were infected with SARS-CoV-2 in the wild. Image credit: Goldberg others., doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-49891-w.

“SARS-CoV-2 could be transmitted from humans to wild animals during contact between humans and wild animals, in the same way that a hitchhiker might jump to a new, more suitable host,” said Carla Finkelstein, a professor at Virginia Tech.

“The goal of a virus is to spread in order to survive. It wants to infect as many humans as possible, but vaccination protects many of us. So the virus turns to animals, where it adapts and mutates to thrive in a new host.”

SARS CoV-2 infections have previously been identified in wild animals, primarily white-tailed deer and wild mink.

This new research significantly expands the number of species investigated and improves our understanding of virus transmission in and between wild animals.

The data suggest that exposure to the virus is widespread among wild animals and that areas with high human activity may be contact points for interspecies transmission.

“This study was prompted by the realization that there were significant and important gaps in our knowledge about the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in the broader wildlife community,” said Dr. Joseph Hoyt of Virginia Tech.

“Most studies to date have focused on white-tailed deer, but we still don't know what's going on with many of the wildlife species commonly found in our backyards.”

For the study, the researchers collected 798 nasal and oral swabs from animals that had been caught live and released from the wild, or that were being treated at a wildlife rehabilitation center, as well as 126 blood samples from six animal species.

These sites were chosen to compare the presence of viruses in animals across different levels of human activity, from urban areas to remote wilderness.

The scientists also identified two mice with the exact same mutation on the same day and in the same location, indicating that they either both got infected from the same person, or one had transmitted it to the other.

How it spreads from humans to animals is unknown, but wastewater is a possibility, but trash cans and discarded food are more likely sources.

“I think the biggest takeaway from this study is that this virus is everywhere. We're finding it in common backyard animals that are testing positive,” said Dr. Amanda Goldberg of Virginia Tech.

“This study highlights the potentially broad host range of SARS-CoV-2 in nature and how widely it may actually spread,” Dr Hoyt said.

“There is much work to be done to understand which wildlife species, if any, are important in the long-term maintenance of SARS-CoV-2 in humans.”

“But what we've already learned is that SARS CoV-2 is not just a human problem, and we need multidisciplinary teams to effectively address its impacts on different species and ecosystems,” Professor Finkelstein said.

of Investigation result Published in today's journal Nature Communications.

_____

A.R. Goldberg others2024. Widespread exposure to SARS-CoV-2 in wildlife communities. Nat Community 15, 6210; doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-49891-w

This article has been edited based on the original release from Virginia Tech.

Source: www.sci.news