Protein fragments survived in the extreme environment of Rift Valley, Kenya

Ellen Miller

In Kenya, fossilized teeth from an 18 million-year-old mammal yielded the oldest protein fragment ever discovered, extending the age record for ancient proteins by fivefold.

Daniel Green at Harvard, alongside Kenyan scientists, unearthed diverse fossil specimens, including teeth, in Kenya’s Rift Valley. Volcanic activity facilitated the preservation of these samples by encasing them in ash layers, enabling the age dating of the teeth to 18 million years. Nonetheless, it remained uncertain whether the protein in the tooth enamel endured.

The circumstances were not promising—Rift Valley is “one of the hottest places on Earth for the past 5 million years,” Green observes. This extreme environment presents “significant challenges.” Despite this, earlier research has detected tooth enamel proteins, albeit not from such ancient samples. To assess the longevity of protein traces, Green employed a small drill to extract powdered enamel from the teeth.

These samples were sent to Timothy Creland at the Smithsonian Museum Conservation Institute for analysis. He utilized mass spectrometry to categorize each molecular type in the sample by differentiating them by mass.

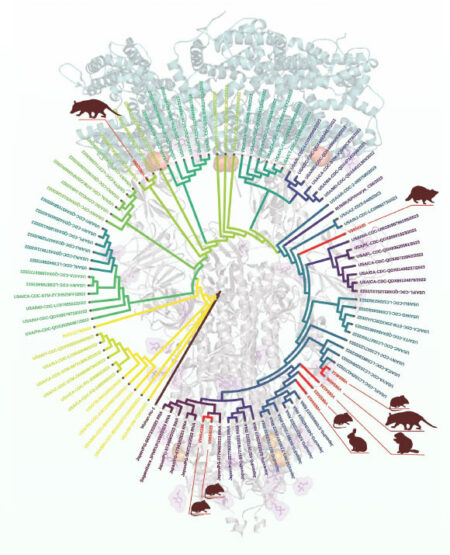

To his surprise, Creland uncovered sufficient protein fragments to yield significant classification insights. This identified the teeth as belonging to the ancient ancestors of elephants and rhinos, among other evidence. Creland expresses enthusiasm for demonstrating that “even these ancient species can be integrated into the Tree of Life alongside their modern relatives.”

While only a small amount of protein was recovered, the discovery remains monumental, asserts Frido Welker from the University of Copenhagen, Denmark. He emphasizes that growing protein and gaining insights into this ancient fossil is a “tremendous breakthrough.”

Unlike other tissues such as bone, sampling teeth is crucial for uncovering fragments of ancient and valuable proteins like these. “The sequence of enamel proteins varies slightly,” notes Creland.

The dental structure may have played a role in preserving proteins for such an extended period. As teeth are “primarily mineral,” these minerals assist in protecting enamel proteins through what Cleland describes as “self-chemical processes.” Furthermore, the enamel comprises only a small fraction of protein, aiding in its preservation, roughly 1%. “Whatever protein is present, it’s going to persist much longer,” Green asserts.

The endurance of protein fragments in Rift Valley suggests that fossils from other locales may also contain proteins. “We can genuinely begin considering other challenging regions of the planet, where we might not expect significant preservation,” Cleland comments. “Microenvironmental discrepancies may promote protein conservation.”

Beyond studying proteins from these specific periods, researchers aim to explore samples from various epochs. “We’re looking to delve deeper into history,” Cleland mentions. Green adds that analyzing younger fossils could offer a “baseline of expectation” for the number of conserved protein fragments compared to those from ancient specimens.

“We’re only beginning to scratch the surface,” Cleland concludes.

topic:

Source: www.newscientist.com