Here’s your content rewritten while maintaining the HTML tags:

Spinning ultracold atoms could uncover the limits of Einstein’s relativity

Shutterstock / Dmitriy Rybin

Small Ferris wheels made from light and extremely chilled particles could enable scientists to investigate elements of Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity on an extraordinary level.

Einstein’s special and general theories of relativity, established in the early 20th century, transformed our comprehension of time by illustrating that a moving clock can tick slower than a stationary one. If one moves rapidly or accelerates significantly, time measured will also increase. The same applies when an object moves in a circular path. While these effects have been noted in relatively large celestial entities, Vassilis Rembesis and his team at King Saud University in Saudi Arabia have developed a method to test these principles on a diminutive scale.

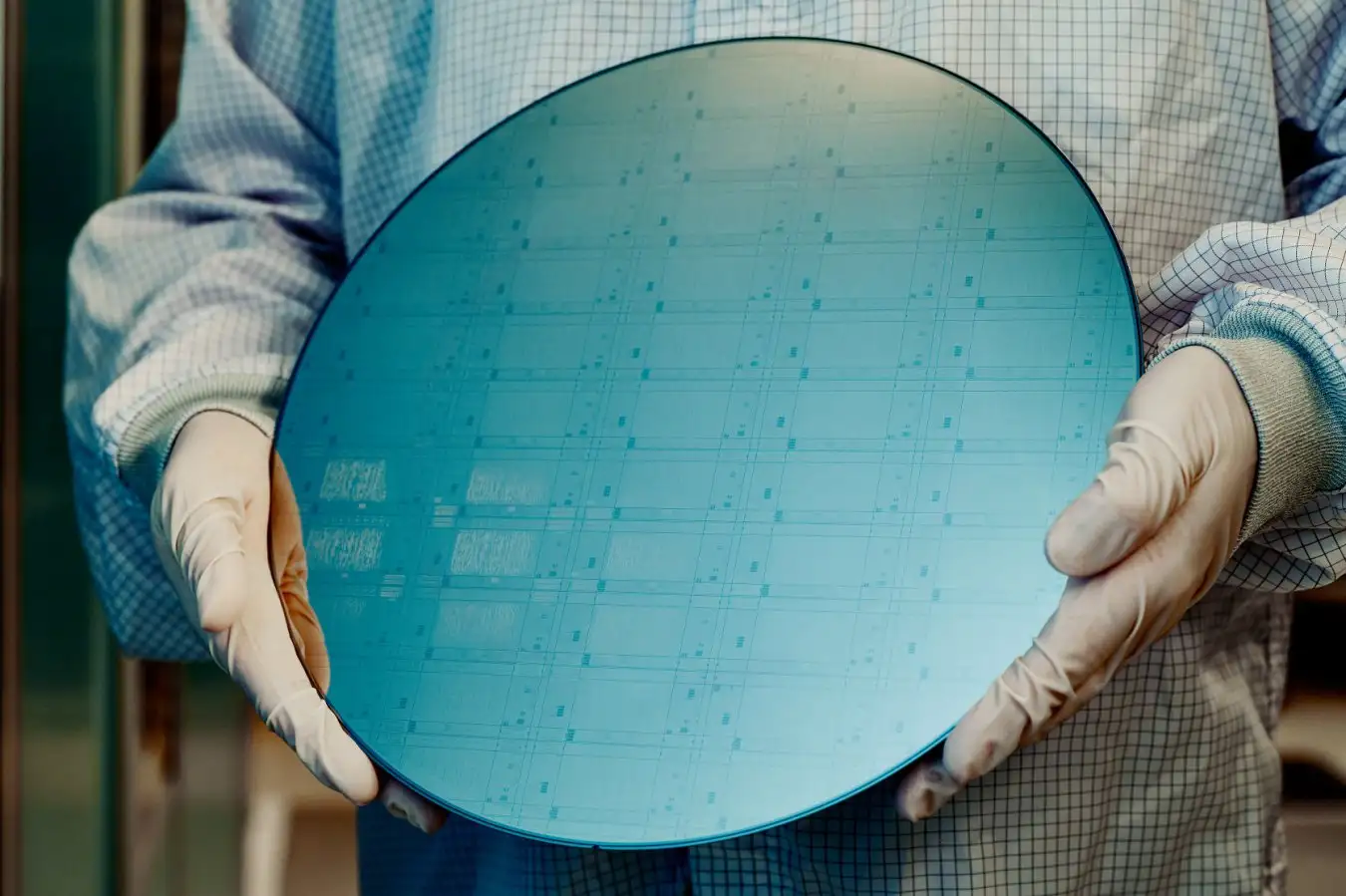

By examining rotation and time at the molecular level (atoms and molecules), they explored ultracold regions, just a few millionths of a degree above absolute zero. In this domain, the quantum behavior and movement of atoms and molecules can be meticulously controlled with laser beams and electromagnetic fields. In 2007, Rembesis and his colleagues formulated a technique to tune a laser beam to trap atoms in a cylindrical form, allowing them to spin. They refer to this as an “optical Ferris wheel,” and Rembesis asserts that their new findings propose that it can be used to observe relativistic time dilation in ultracold particles.

Their predictions indicate that nitrogen molecules are optimal candidates for investigating rotational time delays at the quantum level. By considering the movement of electrons within them as the ticks of an internal timer, the researchers detected frequency changes as minuscule as 1/10 quintillion.

Simultaneously, Rembesis noted that experiments utilizing optical Ferris wheels have been sparse up until now. This new proposal opens avenues for examining relativity theory in uncharted conditions where new or surprising phenomena may emerge. For instance, the quantum characteristics of ultracold particles may challenge the “clock hypothesis,” which states how a clock’s acceleration influences its ticking.

“It’s crucial to validate our interpretations of physical phenomena within nature. It’s often during unexpected occurrences that we need to reevaluate our understanding for a deeper insight into the universe. This research offers an alternative approach to examining relativistic systems, providing distinct advantages over traditional mechanical setups,” says Patrick Oberg from Heriot-Watt University, UK.

Relativistic phenomena, such as time dilation, generally necessitate exceedingly high velocities; however, optical Ferris wheels enable access to them without the need for impractically high speeds, he explains. Aidan Arnold from the University of Strathclyde, UK adds, “With the remarkable accuracy of atomic clocks, the time difference ‘experienced’ by the atoms in the Ferris wheel should be significant. Because the accelerated atoms remain in close proximity, there is ample opportunity to measure this difference,” he states.

By adjusting the focus of the laser beam, it may also become feasible to manipulate the dimensions of the Ferris wheel that confines the particles, allowing researchers to explore time-delay effects for various rotations, as noted by Rembesis. Nevertheless, technical challenges persist, including the need to ensure that atoms and molecules do not heat up and become uncontrollable during rotation.

topic:

Source: www.newscientist.com