Images generated by AI depicting extreme poverty, children, and survivors of sexual violence are increasingly populating stock photo platforms and are being utilized by prominent health NGOs, according to global health specialists who raise alarms over a shift towards what they term “poverty porn.”

“They are widespread,” shares Noah Arnold from Fair Picture, a Switzerland-based organization dedicated to fostering ethical imagery in global development. “Some organizations are actively employing AI visuals, while others are experimenting cautiously.”

Arseni Alenichev, researcher states, “The images replicate the visual lexicon of poverty: children with empty plates, cracked earth, and other typical visuals,” as noted by researchers at the Institute of Tropical Medicine in Antwerp specializing in global health imagery.

Alenichev has amassed over 100 AI-generated images depicting extreme poverty intended for individuals and NGOs to use in social media initiatives against hunger and sexual violence. The visuals he provided to the Guardian reflect scenes that perpetuate exaggerated stereotypes, such as an African girl dressed in a wedding gown with tears on her cheeks. In a comment article published Thursday, he argues that these images represent “poverty porn 2.0”.

While quantifying the prevalence of AI-generated images is challenging, Alenichev and his team believe their usage is rising, driven by concerns regarding consent and financial constraints. Arnold mentioned that budget cuts to NGO funding in the U.S. exacerbate the situation.

“It’s evident organizations are beginning to consider synthetic images in place of real photographs because they are more affordable and eliminate the need for consent or other complications,” Alenichev explained.

AI-generated visuals depicting extreme poverty are now appearing abundantly on popular stock photo websites, including Adobe Stock Photography and Freepik when searching for terms like “poverty.” Many of these images carry captions such as “Realistic child in refugee camp,” and “Children in Asia swim in garbage-filled rivers.” Adobe’s licensing fees for such images are approximately £60.

“They are deeply racist. They should never have been published as they reflect the worst stereotypes about Africa, India, and more,” Alenichev asserted.

Freepik’s CEO Joaquín Abela stated that the accountability for usage of these extreme images falls upon media consumers rather than platforms like his. He pointed out that the AI-generated stock photos come from the platform’s global user base, and if an image is purchased by a Freepik customer, that user community earns a licensing fee.

He added that Freepik is attempting to mitigate bias present elsewhere in its photo library by “introducing diversity” and striving for gender balance in images of professionals like lawyers and CEOs featured on the site.

However, he acknowledged limitations in what can be achieved on his platform. “It’s akin to drying the ocean. We make efforts, but the reality is that if consumers worldwide demand images in a specific manner, there’s little anyone can do.”

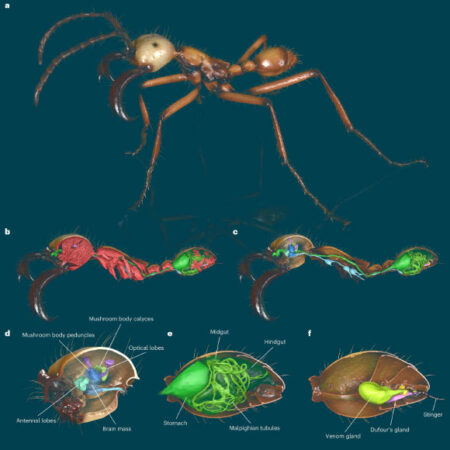

A screen capture of an AI-generated image of “poverty” on a stock photo site, raising concerns about biased depictions and stereotypes.

Illustration: Freepik

Historically, prominent charities have integrated AI-generated images into their global health communication strategies. In 2023, the Dutch branch of the British charity Plan International will launch a video campaign against child marriage featuring AI-generated images including that of a girl with black eyes, an elderly man, and a pregnant teenager.

Last year, the United Nations released a video that showcased the AI-generated testimony of a Burundian woman who was raped and left for dead in 1993 amidst the civil war. This video was removed after The Guardian reached out to the UN for a statement.

“The video in question was produced over a year ago utilizing rapidly advancing tools and was taken down because we perceived it to demonstrate inappropriate use of AI, potentially jeopardizing the integrity of the information by blending real footage with nearly authentic, artificially generated content,” remarked a UN peacekeeping spokesperson.

“The United Nations remains dedicated to supporting survivors of conflict-related sexual violence, including through innovative and creative advocacy.”

Arnold commented that the rising reliance on these AI images is rooted in a long-standing discussion concerning ethical imagery and respectful storytelling concerning poverty and violence. “It’s likely simpler to procure an off-the-shelf AI visual, as it’s not tied to any real individual.”

Kate Kaldle, a communications consultant for NGOs, expressed her disgust at the images, recalling previous conversations about the concept of “poverty porn” in the sector.

“It’s unfortunate that the struggle for more ethical representation of those experiencing poverty has become unrealistic,” she lamented.

Generative AI tools have long been known to reproduce—and at times exaggerate—widely-held societal biases. Alenichev mentioned that this issue could be intensified by the presence of biased images in global health communications, as such images can circulate across the internet and ultimately be used to train the next wave of AI models, which has been shown to exacerbate prejudice.

A spokesperson for Plan International noted that as of this year, the NGO has “adopted guidance advising against the use of AI to portray individual children,” and that their 2023 campaign employed AI-generated images to maintain “the privacy and dignity of real girls.”

Adobe opted not to comment.

Source: www.theguardian.com