MaPregnant women have become familiar with their first look at the baby through a blurry, black-and-white ultrasound scan that they share with loved ones. However, in many parts of the world, this is still considered a luxury. AI is now being utilized to create technology that can provide this essential pregnancy milestone to those who truly need it: a health check-up on their baby.

A pilot project in Uganda is utilizing AI software in ultrasound imaging not just to scan the fetus but also to encourage women to seek medical services early on in their pregnancy, aiming to reduce stillbirths and complications.

In low- and middle-income countries, the availability of trained experts and equipment to conduct these scans is mainly limited to urban hospitals, making the journey from rural areas long and costly for women.

Dr. Daniel Lukakamwa, an obstetrician-gynaecologist at Kawempe National Hospital in Kampala, Uganda, who is involved in the development of the AI software, underscores the importance of early pregnancy examinations in saving lives.

“Pregnant women are increasingly interested in undergoing ultrasound scans,” Lukakamwa stated. “There’s a high willingness to participate in the study without any hesitations. It seems that we are getting overwhelmed.”

Lukakamwa emphasized the significance of tackling delayed births within obstetric care. He added, “The early stages of pregnancy are critical because any abnormalities or subsequent complications can lead to stillbirth.”

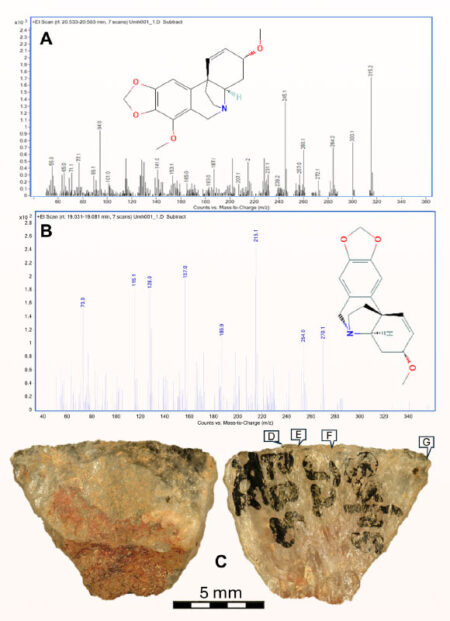

A software called ScanNav FetalCheck Software based on AI has been developed by Intelligent Ultrasound. It enables precise dating of a pregnancy without the need for a specialized ultrasound technician to assess the fetus’s progress inside the uterus.

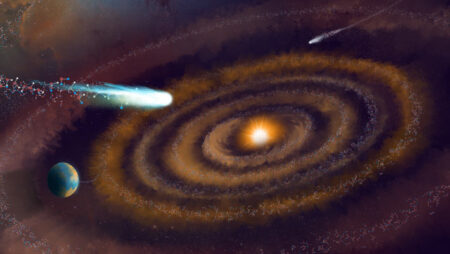

This technology allows for accurate pregnancy dating without the need for a specialized ultrasound technician. Photo: @GEHealthcare

One of several AI programs for pregnancy assessment is currently undergoing testing, with promising early results reported by developers.

The technology enables midwives or nurses to perform the scan by simply placing an ultrasound probe on a woman’s abdomen, with the program providing the necessary data. It can also be used with a portable device for in-home care.

A significant aim of the trial at Kawempe Hospital is to develop a tool that can predict which pregnancies are at the highest risk of stillbirth, while also aiding in engaging with women at an early stage.

Radiologist Jones Biira mentioned, “Mothers who have given birth are referring us to take part in studies. They talk to the mothers and more and more are joining the research programme. They really like it and they trust our findings.”

The primary concern facing the staff is “probably the power outages,” she noted.

For Sarah Kyolaba, 30, from Kikoni village, the technology has given her more control over her second pregnancy.

“You can see how the baby is moving and how the organs are developing,” she says. “When you do a scan, you can see everything. It’s good to see that the baby is thriving and moving.”

She discovered during her first pregnancy that her baby was too large and would require a Caesarean section shortly before delivery, catching her off-guard. “They told me I had to have a Caesarean section, but I wasn’t prepared for that,” she disclosed.

AI is involved in the largest study ever to evaluate the use of aspirin in preventing pre-eclampsia. Clinical trials are ongoing in Kenya, Ghana, and South Africa to compare the impact of two different aspirin doses on women at high risk of pre-eclampsia.

After newsletter promotion

Accurate gestational age is critical for this trial because the risk of pre-eclampsia changes as pregnancy progresses, and early administration of aspirin depends on knowing the exact gestational age.

Dr. Angela Koech, an obstetrician in rural Kenya and a research scientist at the Aga Khan University in Nairobi, emphasized the importance of knowing the precise number of weeks pregnant.

Dr. Alice Papageorgiou, co-founder of Intelligent Ultrasound, believes that AI can enable hospitals in disadvantaged countries to “develop the same capacity as higher-income countries.” Photo: Intelligent Ultrasound

“One of the biggest challenges I face is when a mother develops complications, typically in the later stages of pregnancy, and I have to make decisions,” Koech explained, highlighting the role of leading research leading to the AI ultrasound program.

“For instance, if a woman presents with pregnancy-induced hypertension or preeclampsia in the third trimester, I may have to decide on the timing of delivery based on the baby’s survival odds. The decision varies significantly based on whether the woman is 30, 32, 34, 36, or 38 weeks along.”

Koech emphasized the risks of delivering extremely premature babies in rural facilities lacking neonatal care units. She said, “When a mother gives her last period as pregnancy age but you’re uncertain, the decision becomes very challenging and unreliable.”

Many individuals in rural Kenya delay seeking medical assistance until late in pregnancy, with some considering it inappropriate to announce a pregnancy early, while the expenses and long travel time to antenatal clinics present further challenges.

Dr. Alice Papageorgiou, co-founder of Intelligent Ultrasound and director of clinical research at the Oxford Institute of Maternal, Child and Perinatal Health, acknowledges concerns that the technology could be viewed as providing subpar services to women in lower-income countries.

“Ideally, we should focus on building capacity in these environments by providing the right equipment, training, and resources similar to high-income countries. However, the reality is that this hasn’t been accomplished in recent decades. So, as an interim solution – one that may only be temporary – I believe it is a good solution,” she concluded.

Source: www.theguardian.com