oWhen Russia’s invasion of Ukraine commenced, Leksii Sukhorukov’s son was just 12 years old. For months, their family endured trauma and uncertainty. Sukhorukov had to leave his job in the entertainment sector, which included virtual reality and video games, leading to isolation from friends and family. Amid all this chaos, his son found solace in Minecraft. No matter the turmoil outside, he could enter Mojang’s block-building game to escape.

“After February 24, 2022, my perspective on the game shifted dramatically,” Skorkov reflects. He discovered a community of Ukrainian children playing together online. Some lived under Russian occupation, while others resided in government-controlled regions frequently targeted by missile strikes. Many had become refugees, yet they managed to connect, support each other, and construct their own worlds. Isn’t that fascinating? I felt compelled to explore how video games could be harnessed for this purpose.”

Sukhorukov, who holds a degree in psychology, chose to return to his roots, aiming to integrate his gaming experience with mental health practices. He is now the MC of the Ukrainian National Psychological Association’s Cyber Psychology Department. In 2023, he launched HealGame Ukraine, a project focused on utilizing video games for mental and emotional health support. “Currently, in collaboration with the Donetsk National Institute of Technology, we are developing a Minecraft server aimed at bringing together Ukrainian children who feel particularly isolated due to the conflict,” he explains. “The server will be facilitated by psychologists and social workers, and we also plan to create a Minecraft project for children with special educational needs.”

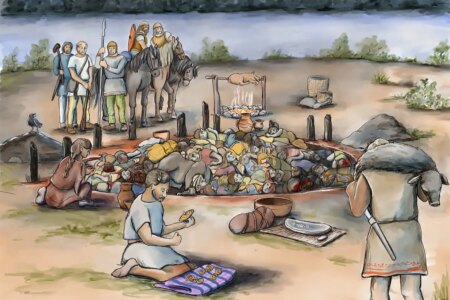

Lighthouse…Moment from Oleksii Sukhorukov’s Wonderworld project, where kids create towers to connect with each other on Minecraft servers. Photo: оacy

Play has been a foundation of child therapy for nearly a century, thanks to pioneers like Anna Freud, Melanie Klein, and Virginia Axlein. However, the integration of video games into therapy has been spearheaded by a new generation of practitioners who grew up gaming since the early 2010s. In 2011, Massachusetts-based therapist and gamer Minecra Grova published “Reset: Video Games and Psychotherapy,” a guide for clinicians seeking to understand gaming culture’s impact on adolescents. This piqued the interest of UK counselor Ellie Finch. Growing up with Mega Drive games, she began contemplating how to incorporate games into therapy after engaging with titles like Nie and Minecraft in 2012. However, the onset of the pandemic halted her plans.

“I transitioned from in-person youth counseling to online sessions overnight,” Finch recalls. “There are limitations to providing counseling via video calls, and I noticed many of the children were gamers. I began discussing video games with them.

Minecraft has shown to be particularly effective for several reasons: it’s one of the most popular games globally, with over 200 million players, making it familiar and accessible to many kids. Its open and creative structure allows players to express themselves freely, gathering materials to construct homes, explore, and fend off zombies.

Finch creates a private Minecraft environment exclusively for her and the children she works with. Clients can dictate parameters; some may prefer no hostile characters and opt for creative mode, while others desire a flat sky landscape. “I often begin the first session by asking my clients to design a safe space in their world,” Finch states. “This could be a house, castle, or underwater observatory. Their creations reveal much about their inner world right from the start.”

The ideal home… Ellie Finch guides clients in building a secure home within Minecraft. Photo: Microsoft/Ellie Finch

Therapists can navigate the game in various ways, allowing for a non-directed format where they follow the client to develop trust and employ therapeutic skills to decode the ongoing dynamics. “Minecraft provides a sense of adventure,” Finch notes. “Clients might wish to explore caves, swim underwater, battle hostile mobs, or construct intricate machines, opening a multitude of possibilities.

Therapists can also employ commands that engage clients in therapeutic or psychoeducational tasks. Recently, Sukhorukov and Ukrainian psychologist Anna Schulha, along with nonprofit Martesezer Werke, orchestrated a quest called Wonderworld for Ukrainian refugees aged 11-13 in Germany. These children, often feeling isolated and burdened by forced migration, participated in sessions where they had to find envelopes containing Minecraft-related resources hidden around their living spaces and nearby parks. They then utilized these resources in the game to create cakes and other items.

“At the conclusion of each session, we encouraged kids to reflect on the positive emotions and experiences they encountered during the game,” Skorkov shares. “It’s fascinating to observe the kids’ constructions and the choices they make. Are they vibrant and open, or concealed underground? How do they navigate this gaming realm?

Finch resonates with the notion that creativity within video games serves as a medium of communication, akin to drawing or building with LEGO. “The kids have shown me their fears and feelings of entrapment by guiding me into dark caves. They constructed slime block trampolines to relieve tension. Teenagers have utilized the game to venture outside their ‘safe spaces’ and explore unfamiliar territories beyond the guidance of therapists and trusted adults. In 2024, she plans to collaborate with the Cambridge University Faculty of Education on a project named ‘Chasm: Creating Accessible Services Using Minecraft’ to showcase these therapeutic uses.

Today, an increasing number of therapists are exploring the potential of video games in diverse ways. Drawing influence from Sukhorukov, they’re doing essential work that elucidates the digital landscape, cyber trauma, and the realities children face in gaming.

It’s not just about Minecraft. Games like Fortnite, Roblox, and Animal Crossing are also becoming therapeutic tools. Regardless of the game, therapy is essential in reflecting the increasingly digital lives of our youth. “For individuals raised in a tech-rich world, digital play isn’t merely a pastime,” Stone asserts. “They utilize platforms, programs, and devices as their primary forms of creativity and connection, amplifying the foundations of psychotherapy rather than replacing them.

Finch is currently contemplating extending video game therapy to adults, recognizing that this approach can be beneficial across all ages, given her lifelong devotion to gaming.

For Sukhorukov, a profound dynamic exists between Ukrainian children and Minecraft. The therapeutic impact is expanding throughout the nation. “If you search for the term ‘майнкрафт’ on Ukrainian YouTube, you will find numerous videos created by Ukrainian children and teenagers within Minecraft. They reflect lives intersected by war, with military parents, loved ones, or displaced companions. The war has fragmented their connections, affecting every Ukrainian child.

“Moreover, there’s something else that may be challenging to convey. The homelands of many Ukrainians—Volnovakha, Sievierodonetsk, Soledar, Mar’inka, Bakhmut—only exist in Minecraft. Children lack the capacity to articulate their experiences in extensive articles about these realities.

Source: www.theguardian.com