aAmong those quickly convicted and sentenced recently for their involvement in racially charged riots were: Bobby Silbon. Silbon exited his 18th birthday celebration at a bingo hall in Hartlepool to join a group roaming the town’s streets, targeting residences they believed housed asylum seekers. He was apprehended for vandalizing property and assaulting law enforcement officials, resulting in a 20-month prison term.

While in custody, Silbon justified his actions by asserting their commonality: “It’s fine,” he reassured officers. “Everyone else is doing it too.” This rationale, although a common defense among individuals caught up in gang activity, now resonates more prominently with the hundreds facing severe sentences.

His birthday festivities were interrupted by social media alerts, potentially containing misinformation about events in Southport. Embedded in these alerts were snippets and videos that swiftly fueled a surge in violence without context.

Bobby Charbon left a birthday party in Hartlepool and headed to the riots after receiving a social media alert.

Picture: Cleveland Police/PA

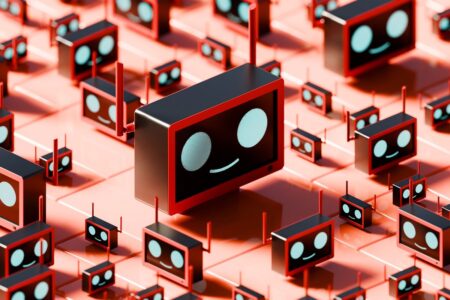

Mobile phone users likely witnessed distressing scenes last week: racists setting up checkpoints in Middlesbrough, a black man being assaulted in a Manchester park, and confrontations outside a Birmingham pub. The graphic violence, normalized in real-time, incited some to take to the streets, embodying the sentiment of “everyone’s doing it.” In essence, a Kristallnacht trigger is now present in our pockets.

A vintage document from the BBC, the “Guidelines Regarding Violence Depiction,” serves as a reminder of what is deemed suitable for national broadcasters. Striking a balance between accuracy and potential distress is emphasized when airing real-life violence. Specific editorial precautions are outlined for violence incidents that may resonate with personal experiences or can be imitated by children.

Social media lacks these regulatory measures, with an overflow of explicit content that tends to prioritize sensationalism over accuracy, drawing attention through harm and misinformation.

Source: www.theguardian.com