In the summer of 1985, I embarked on a lengthy pilgrimage from my home in Cheadle Hulme to the charming Hammersmith Novotel in London for the Commodore Computer Show. As a 14-year-old gamer, I saw this as an opportunity to play the latest games and check out new gaming accessories. However, my main goal was to visit specific exhibitors that I was eager to see. Upon arrival, I noticed a long line of kids at small stands, most of them waiting to get their show program signed by arcade games champion and ZZAP reviewer Julian Lignoll. As a devoted subscriber, I remember the excitement of waiting in that line. I didn’t experience that level of awe again until I met Sigourney Weaver a quarter of a century later.

I’m sure I’m not the only one who remembers that day. In his fantastic new book, The Games of a Lifetime, Rignall himself recalls the surprise of being swarmed by fans. He writes, “We didn’t anticipate that. I didn’t realize that readers were so interested in us, but I loved it.”

However, I don’t think he should have been so surprised. In the mid-80s, during the heyday of C64 and ZX Spectrum home computers, magazines like Crash, ZZAP, and Computer & Video Games were the primary sources of news and opinions about new games. There was a scarcity of information about game developers at the time, so magazine reviewers became industry stars and influencers of that era, even before the rise of social media.

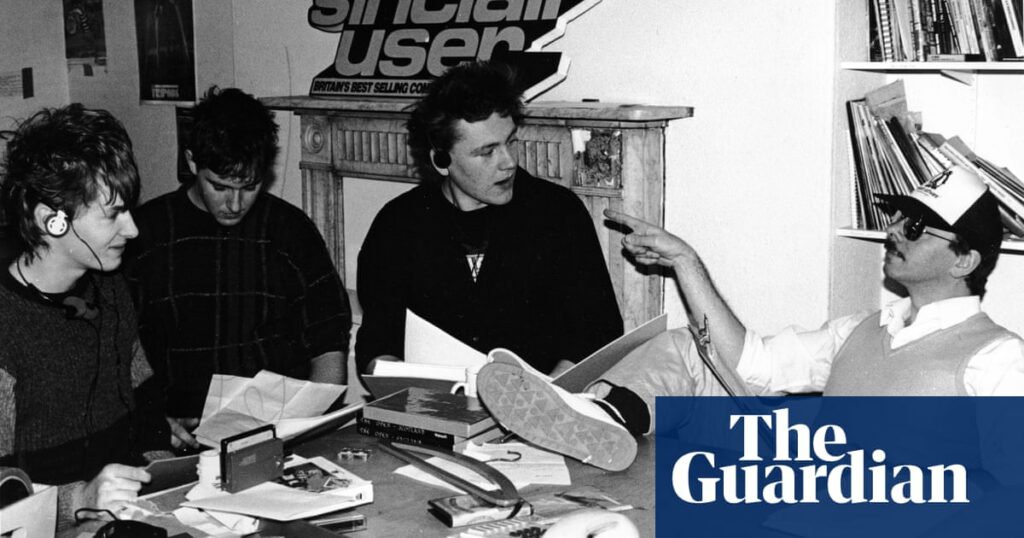

What I find most captivating about Rignall’s books is tracing his journey from Seaside Arcade Tournaments to game development editing and eventually becoming the editorial director at Mammoth Video Game Site IGN. As a child, I pictured a lavish, high-tech publishing office in a sleek modernist building. However, Zzap! 64’s origins were in a small rented office in Yeovil. Rignall recalls, “We were all crammed into one room with a few C64s tucked away in the broom cupboard. Video games were always considered lowbrow, but in those early days, it was truly Dickensian.”

Major magazine companies weren’t as glamorous as one might think. When Rignall worked for C&VG in 1988, he transitioned from a relatively small newsroom to the sprawling EMAP headquarters in Farringdon, London. As he remembers, “It was a dusty pit with typewriters, smelly carpets, and outdated interior fixtures that looked like they hadn’t been updated since the 1970s. Oh, and ashtrays filled with cigarette butts were everywhere.”

Matt Bielby, who went on to launch legendary game magazines Superplay and PC Gamer, transitioned from being a C&VG junior writer to joining Sinclair at Dennis Publishing. “Dennis was even dingier and smokier than EMAP,” he recalls. “It was housed in several small buildings along the northern end of Oxford Street at Tottenham Court Road; initially, we were stacked on top of each other with computer shoppers, kits precariously balancing on shaky desks… I had to share a desk initially.”

In the mid-80s, Your Sinclair emerged as a pioneer of a new style of irreverent and personality-driven gaming journalism. Earlier home computer magazines focused on programming tips and articles about printers and word processing software, but these new publications put games front and center. Sinclair’s founding editor, Teresa Morgan, drew inspiration from reading Smash Hits at just 17. She recalls, “They had a distinct voice and made their writers visible. So, intentionally, we included caricatures of reviewers in the magazine. Everyone could express their personality, making readers feel connected to us.”

This connection sometimes led to strange encounters. “I remember receiving all sorts of odd things in the mail,” says Morgan. “Someone once sent me my own toenails.”

Like Smash Hits, Your Sinclair became known for developing its unique language and humor, creating silly photo stories reminiscent of Jackie magazine, and covering quirky games like a lawnmower simulator developed by magazine contributor Duncan McDonald. Readers were active participants, with their letters and artwork becoming essential elements of the magazine’s content. Rignall reflects, “By the early ’90s, when we launched the Average Machine, the magazine was 100% designed to be interactive. Text pages, Q&A sections, and editorials were essentially proto-social media before the term was even coined. Readers were encouraged to send in crazy photos, sketches, drawings, you name it. We aimed to create a sense of community run by its members.”

However, the traditional magazine production process was a different story. Before desktop publishing software came into play, everything was done manually. “You would type it up on your Apricot Proto PC, save it to a disk, then hand it over to the typesetter,” Rignall explains. “They would print a galley (print-quality text), cut it out with scissors, and lay out the pages with glue along with photos and other design elements.”

Taking screenshots was an art form of its own. By the time I started at Edge Magazine in 1995, the process had turned digital. I had a program that allowed me to capture screenshots from the console, which then connected to my Mac via a video card. But in the ’80s, it was a different story. “We took screenshots by placing a film camera in front of a clean TV screen and snapping a photo of it,” Rignall recalls. “I had to set up blackout curtains in the game room, turn off all lights, and create a dark environment. It was challenging because I had to synchronize the camera.”

In essence, the production of game magazines was slow, labor-intensive, and at times chaotic as small, young teams churned out dozens of reviews each month. “It’s no wonder that magazines in the mid to late ’80s were riddled with errors,” Rignall comments. “Typos, incorrect information, text in the wrong place, missing elements, inaccuracies… you name it. The process was an absolute mess.”

Yet, in a way, this chaos was part of their charm. Game magazines pushed the limits of publishing technology, and when the digital age arrived, they were often at the forefront of innovative publications using software like Pagemaker and Quark Xpress. Morgan reminisces about launching Zero in 1989, aiming for a more sophisticated gaming magazine. “It had a glossy, highly designed look. We won the European Magazine Award for two consecutive years.”

These magazines were at the heart of video game culture, offering a window into an exciting new world. “The industry was very tight-knit – everyone knew each other,” Morgan recalls. “We had a healthy sense of competition. We would often have developers visit the office, or we’d go to their homes and interview them in their pajamas.”

However, by the late 1980s, the focus shifted from home computers to consoles, with readers seeking direct information from Japan, the birthplace of gaming. Rignall notes, “The one who started writing about Japanese content for British audiences was Tony Takouji in 1987, which kicked off a series of CVG average machines that I took over a year later. I stumbled upon a Japanese bookstore near the EMAP office in 1988, and it was a goldmine. I couldn’t understand what was written until translators were found a month or two later, but I could decipher the game from the screenshots.”

Rignall’s book serves as a memoir of the gaming industry, exploring how games from Battle Zone to Forbidden Forest challenged Western notions of interactive entertainment for both players and journalists. By the time I entered the industry, it had evolved into a more stable and professional environment. Future Publishing operated out of a beautiful building in Bath, while Edge shared Beaufort House, a former Georgian pub, with titles like Super Play and Game Master. It was a thrilling time with great magazines, yet we carried on the legacy of the chaotic magazines that came before us in our spirit, work ethic, and humor.

Morgan looks back fondly on those times, recalling a memorable experience at a Microprose press event. “It was for the Tom Clancy flight simulator. They invited 10 journalists, and we all went on a light aircraft. Wild Bill Steely, MicroProse co-founder and ex-fighter pilot, did loops. I took turns with my sick bag. There was a champagne breakfast on the boat… and the camaraderie with the YS team was incredible. We got to play the game before anyone else. I’ve never laughed that much. It felt like the start of something special.”

Source: www.theguardian.com