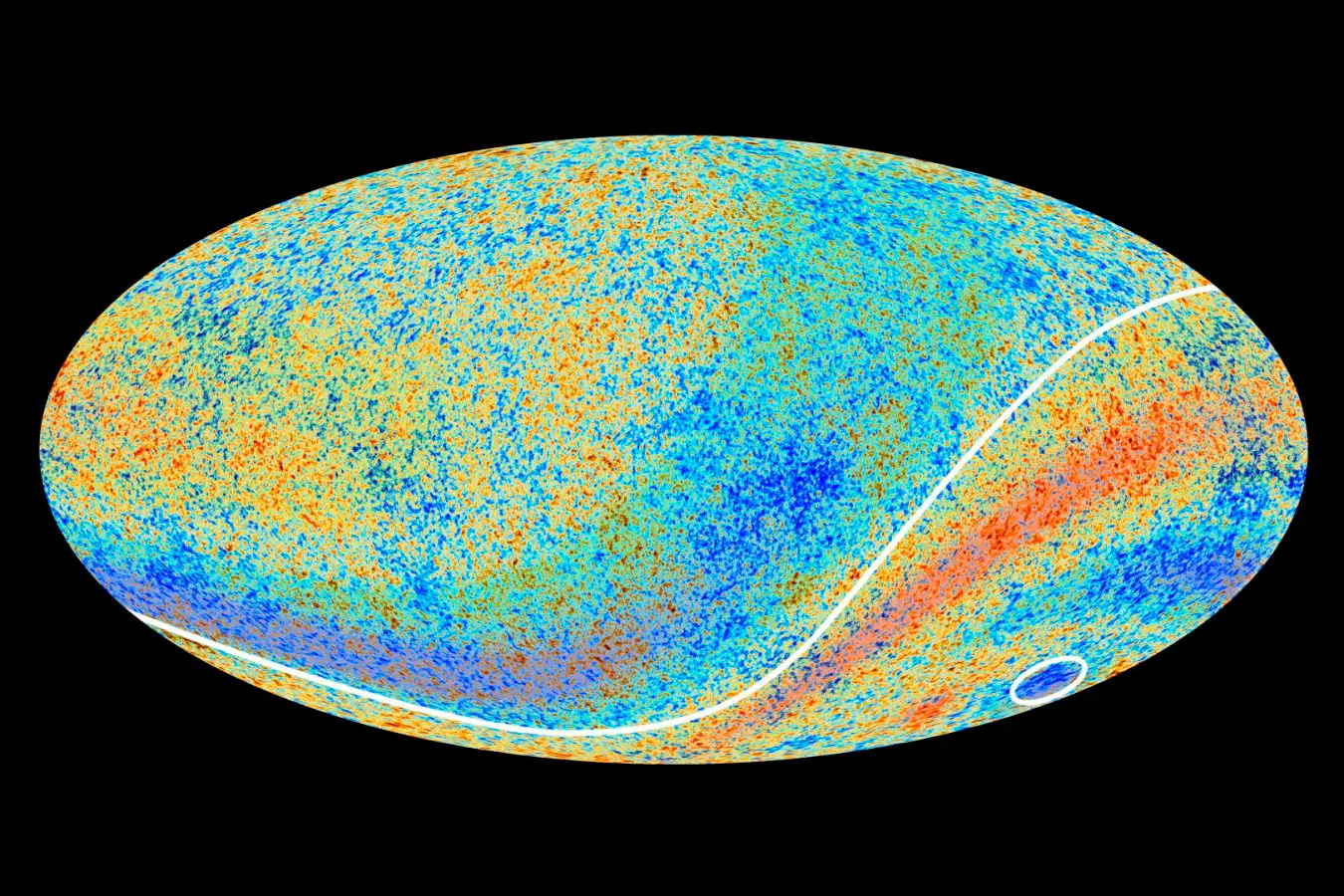

The asymmetry in the average temperature of the cosmic microwave background is inconsistent with the standard model of cosmology

ESA/Planck Collaboration

Cosmic anomalies have puzzled scientists for years, and recent examinations of data from various radio telescopes further complicate the understanding of their origins.

This peculiar fluctuation appears in the afterglow of the Big Bang, representing radiation that has journeyed toward us since the dawn of time, referred to as the cosmic microwave background (CMB). Physicists generally expect this radiation to be uniform in all directions; therefore, significant deviations are perplexing. Current measurements indicate a gradient in CMB temperatures, resulting in colder and hotter areas known as a dipole, as explained by Lucas Behme. His team at Bielefeld University in Germany utilized data from radio telescopes to delve deeply into these anomalies.

Böhme notes that while the presence of the CMB dipole isn’t surprising, its magnitude defies the expectations of our prevailing cosmological models. Radiation emitted from moving sources—and perceived by observers who are also in motion—appears warmer or colder due to the Doppler effect and other relativistic effects. Yet, the dipole observed is approximately ten times more intense than anticipated.

To analyze this discrepancy, Böhme and his colleagues examined data from six radio telescopes and meticulously narrowed their focus to the three most precise measurements. Böhme describes their method as dividing the sky into pixels to determine the number of radiation sources within each. Nevertheless, despite their exhaustive adjustments, the dipole mystery endured.

Dragan Huterer from the University of Michigan finds the team’s thorough analysis noteworthy. He emphasizes that this is crucial for establishing the dipole as an undeniable feature of the CMB. “This is a significant insight, indicating that we fundamentally misunderstand our spatial context within the universe, or that our most accurate theories fail to align with the evidence,” he states. However, Huterer also points out the challenges inherent in accurately measuring radio astronomical data, which may result in systematic errors.

Part of the difficulty lies in the faintness of the radio signals collected, Böhme explains. “We aim to measure extremely subtle phenomena. Fine-tuning this measurement is challenging,” he notes. Yet, this is not the only evidence supporting the existence of the dipole. Infrared radiation from quasars tends to reinforce the findings from radio wave measurements, and forthcoming telescopes may enhance precision in observations, potentially resolving some of the dipole’s enigmas.

Reference: Physical Review Letter, available here

Topic:

Source: www.newscientist.com