Scientists have discovered that methane trapped beneath Svalbard’s permafrost could escape and put it at risk of a warming cycle. Frequent methane accumulations found in well exploration highlight the potential for increased global warming as permafrost thaws. Credit: SciTechDaily.com

Scientists say large amounts of methane may be trapped beneath the permafrost and could escape if it thaws.

Research in Svalbard has shown that methane is moving beneath the permafrost. Lowland regions have ice-rich permafrost, which acts as an effective gas seal, while highland regions with less ice appear to be more permeable. If permafrost thaws too much, greenhouse gas emissions could leak and temperatures could rise further.

Millions of cubic meters of methane are trapped beneath Svalbard’s permafrost. And scientists now know that methane can escape by moving beneath the cold seal of permafrost. A large-scale escape could create a warming cycle that would cause methane emissions to skyrocket. Global warming will thaw permafrost, releasing more gases; warming will thaw more permafrost, releasing more gases. These mobile methane deposits may exist elsewhere in the Arctic, as Svalbard’s geological and glacial history is very similar to other parts of the Arctic region.

“Methane is a powerful greenhouse gas,” said the study’s lead author, Dr. Thomas Birshall of the Svalbard University Center. Frontiers of Earth Science. “Although leakage from beneath the permafrost is currently very low, factors such as retreating glaciers and thawing of the permafrost could ‘uncover’ the problem in the future.”

Refrigerated

Permafrost, ground that remains below freezing Celsius It has been prevalent in Svalbard for over two years. However, it is not uniform or continuous. The western part of Svalbard is warmer due to ocean currents, so the permafrost can be thinner and more patchy. Permafrost in highlands is drier and more permeable, whereas permafrost in lowlands is saturated with ice. The rocks below are often a source of fossil fuels and emit methane, which is locked away by permafrost. However, even where permafrost exists continuously, gas can escape depending on the geographical features.

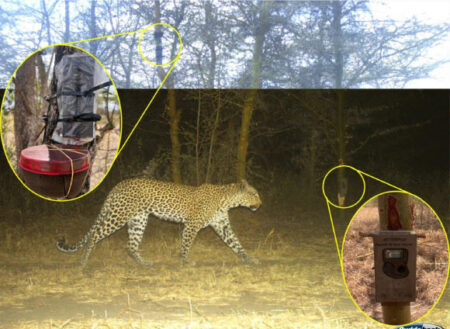

The bottom of permafrost is difficult to study because it is inaccessible. But over the years, many wells have been sunk into permafrost by companies looking for fossil fuels. Researchers used historical data from commercial and research wells to map permafrost across Svalbard and identify permafrost gas accumulations.

“My boss, Kim, and I looked at a lot of historical well data in Svalbard,” Birchall said. “Kim noticed one recurring theme, and that was the accumulation of gas at the bottom of the permafrost.”

Discover methane accumulation

Initial temperature measurements are often compromised by heating the drilling mud to prevent freezing of the wellbore. But by observing trends in temperature measurements and monitoring boreholes over time, scientists were able to identify permafrost. They also looked at ice formation within the wellbore, changes in drill chips produced during drilling of the wellbore, and changes in background gas measurements.

Well monitors confirmed the flow of gas into the wellbore, indicating that gas was accumulating beneath the permafrost, and abnormal pressure measurements indicated that the icy permafrost was acting as a seal. I did. In other cases, the permafrost and underlying geology are suitable for trapping gas, and even if the rock is a known source of hydrocarbons, it may not be present and the gas produced This suggests that they were already on the move.

Unexpectedly frequent discoveries

Scientists stressed that gas buildup is much more common than expected. Of his 18 hydrocarbon exploration wells drilled in Svalbard, eight showed evidence of permafrost, and half of them showed gas accumulation.

“All wells that encounter gas accumulation have done so by chance. In contrast, hydrocarbon exploration wells that specifically target accumulation in more typical environments have a success rate of well over 50%. It was below,” Birchall said. “This seems to be a common occurrence. One anecdotal example comes from a recently drilled well near the airport in Longyearbyen.Drillers heard bubbling coming from the well. So I decided to take a look, equipped with a rudimentary alarm designed to detect explosive levels of methane. As soon as I held the alarm over the well, it went off.”

Impact on climate change

Experts have shown that the active layer of permafrost – the top 1-2 meters that thaws and refreezes seasonally – is expanding as the climate warms. However, little, if any, is known about how deeper permafrost is changing. Understanding this depends on understanding fluid flow beneath permafrost. As permanently frozen permafrost becomes thinner and more splotchy, this methane can move and escape more easily, accelerating global warming and potentially exacerbating the climate crisis.

References: “Natural gas trapped in permafrost in Svalbard, Norway” by Thomas Birchall, Marte Jochman, Peter Bethlem, Kim Senger, Andrew Hodson and Snorre Olaussen, October 30, 2023. Frontiers of Earth Science.

DOI: 10.3389/feart.2023.1277027

Source: scitechdaily.com