A group of paleontologists from Yale University and Stony Brook University made a significant discovery while studying dinosaur fossils, including two bird species found in the Gobi Desert, Mongolia.

This scene illustrates the oviraptorid dinosaur Citipati appearing astonished as it rests on sand dunes. The creature raises its arms in a threat display, exposing its wrists and emphasizing the small, relocated, closed carpal bones (highlighted in blue x-ray). Image credit: Henry S. Sharp.

For years, the identity of a particular carpal bone in the bird’s wrist was a scientific enigma, until researchers determined it functioned as a trap.

This bone, originally resembling a kneecap-like sesame bone, shifted from its original position in the wrist, replacing another carpal bone known as Urna.

Positions in modern birds indicate a link that enables the bird to automatically fold its wings when it bends.

The bone’s large V-shaped notch allows for the alignment of hand bones to prevent dislocation during flight.

Consequently, this bone plays a crucial role in the bird’s forelimb and is integral for flight.

“The carpal bone in modern birds is a rare wrist bone that initially forms within muscle tendons, resembling knee-like bones, but eventually takes the place of the ‘normal’ wrist bones known as Urna,” commented one researcher.

“It is closely associated with the muscle tissue of the arm, linking flying muscle movement to wrist articulation when integrated into the wrist.”

“This integration is particularly vital for wing stabilization during flight.”

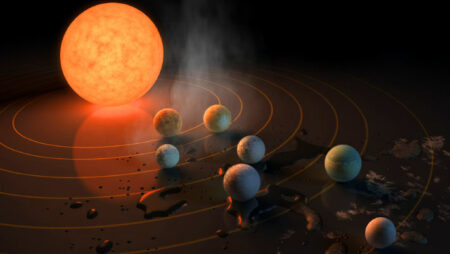

In their recent study, Dr. Bhullar and his team analyzed two Late Cretaceous fossils: Troodontid (birds of prey, related to Velociraptor) and citipati cf. osmorusca (an oviraptorid with a long neck and beakless jaw).

“We were fortunate to have two rigorously preserved theropod wrists for this analysis,” said Alex Rubenstal, a paleontologist from Yale University.

“The wrist bones are small and well-preserved, but they tend to shift during decay and preservation, complicating their position for interpretation.”

“Observing this small bone in its correct position enabled me to thoroughly interpret the fossil wrists we had on hand, as well as those from previous studies.”

“James Napoli, a vertebrate paleontologist and evolutionary biologist at Stony Brook University, noted:

“While it’s unclear how many times dinosaurs learned to fly, it’s fascinating that experiments with flight appear only after they adapted to the wrist joint.”

“This adaptation may have established an automated mechanism found in present-day birds, although further research on dinosaur wrist bones is necessary to validate this hypothesis.”

Placing their findings within an evolutionary framework, the authors concluded that it was not merely birds but rather theropod dinosaurs that underwent the confinement of this adaptation by the origin of Penalaptra, a group of theropods that includes Dromaeosaurids and Oviraptorosaurs like Velociraptor.

Overall, this group of dinosaurs exhibited bird-like features, including the emergence of feathered wings, indicating that flight evolved at least twice, if not up to five times.

“The evolutionary replacement of Urna was a gradual process occurring much deeper in history than previously understood,” stated the researchers.

“In recent decades, our understanding of theropod dinosaur anatomy and evolution has expanded significantly, revealing many classical ‘bird-like’ traits such as thin-walled bones, larger brains, and feathers.

“Our findings suggest that avian construction is consistent with a topological pattern traced back to the origin of Penalaptra.”

The team’s paper was published in the journal Nature on July 9, 2025.

____

JG Napoli et al. Theropod wrist reorganization preceded the origins of bird flight. Nature, Published online on July 9, 2025. doi:10.1038/s41586-025-09232-3

Source: www.sci.news