Paleontologists have discovered a specimen dating back 410 million years: cavernous cavernosa nanum. This lichen is one of the oldest and most extensively distributed in the fossil record and was found in Brazil’s Paraná Basin, specifically within the Ponta Grossa Formation.

Artistically reconstructed cavernous cavernosa nanum from the Early Devonian, depicting high-latitude sedimentary systems of the Paraná Basin. Image credit: J. Lacerda.

The colonization of land and the evolution of complex terrestrial ecosystems rank among the most significant evolutionary milestones in the history of life.

This phenomenon greatly affected terrestrial and marine ecosystems, leading to the sequestration of atmospheric carbon dioxide, enhanced weathering, nutrient absorption in oceans, soil formation, and the emergence of major groups of terrestrial animals.

It is well-established that early plants played a crucial role in land colonization, particularly in establishing the first plant communities.

The earliest records of ancient land plants appear in the form of cryptospores from the Middle Ordovician, around 460 million years ago. The first macrofossils of vascular plants are found in Silurian deposits dating from approximately 443 to 420 million years ago.

Despite this, the specific role and presence of lichens during various stages of terrestrialization remain uncertain.

“cavernous cavernosa nanum displays a partnership of fungi and algae akin to modern lichens,” noted Dr. Bruno Becker Kerber from Harvard University.

“Our research illustrates that lichens are not merely peripheral organisms; they were vital pioneers in reshaping Earth’s terrain.”

“They contributed to the soil formation that enabled the colonization and diversification of plants and animals on land.”

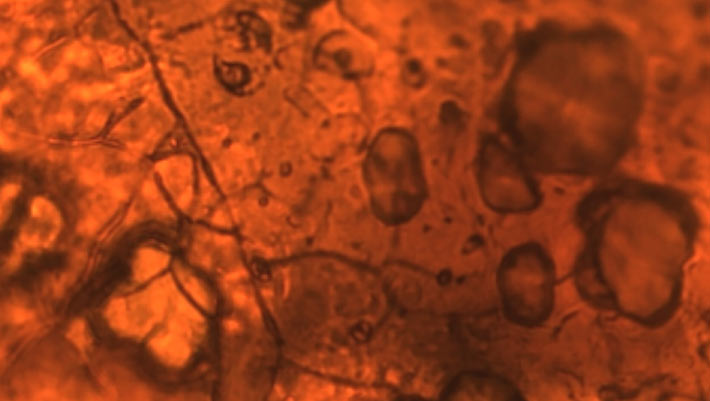

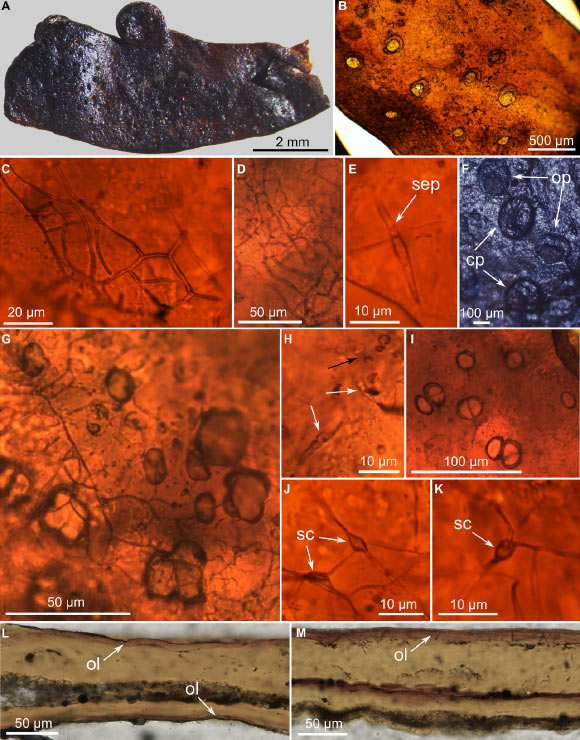

Morphology and internal structure of cavernous cavernosa nanum. Image credit: Becker-Kerber et al., doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adw7879.

Findings indicate that ancient lichens originated in the cold polar regions of the Gondwana supercontinent, now known as parts of modern-day South America and Africa.

“cavernous cavernosa nanum is a remarkable fossil, preserved in an incredible state. Essentially, they are mummified with their organic matter intact,” remarked Professor Jochen Brocks from the Australian National University.

“In simple plants, the tough component is cellulose. In contrast, lichens are unique; they consist of chitin, the same material that gives insects like beetles their strength.”

“Chitin contains nitrogen. In our analyses, cavernous cavernosa nanum yielded an unprecedented nitrogen signal.”

“Such clear results are rare. It was a true Eureka moment.”

“Today, lichens continue to be vital in soil creation, nutrient recycling, and carbon capture in extreme environments spanning from deserts to the polar regions.”

“Yet, due to their delicate structure and infrequent fossil records, their origins remain elusive.”

“This research underscores the necessity of blending traditional techniques with innovative technology,” explained Dr. Nathalie L. Alchira, a researcher at the Synchrotron Light Institute in Brazil.

“Preliminary measurements enabled us to identify crucial areas of interest and collect 3D nanometer imaging for the first time, unveiling the intricate fungal and algal networks that define cavernous cavernosa nanum as a true lichen.”

The team’s study was published in this week’s edition of Scientific Advances.

_____

Bruno Becker-Kerber et al. 2025. The role of lichens in the colonization of terrestrial environments. Scientific Advances 11(44); doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adw7879

Source: www.sci.news