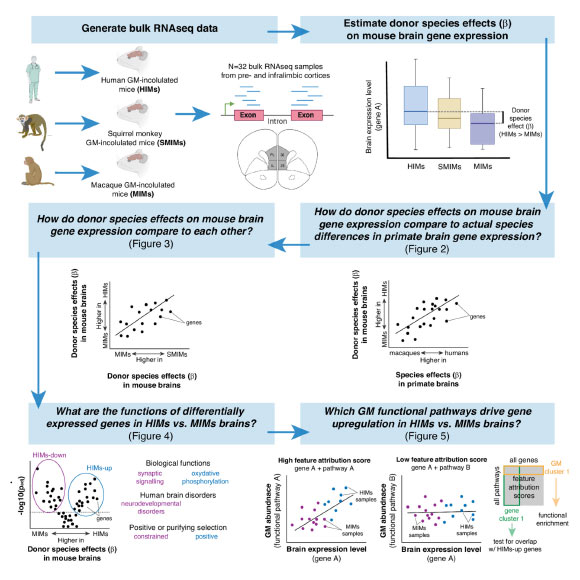

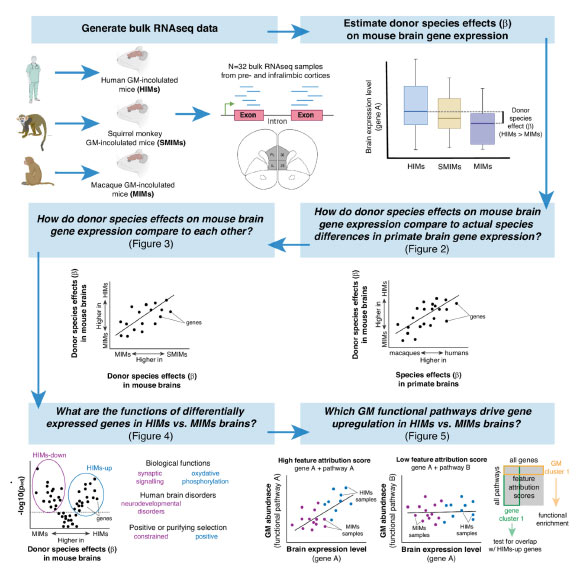

Humans have larger brains relative to body size compared to other primates, which leads to a higher glucose demand that may be supported by gut microbiota changes influencing host metabolism. In this study, we investigated this hypothesis by inoculating germ-free mice with gut bacteria from three primate species with varying brain sizes. Notably, the brain gene expression in mice receiving human and macaque gut microbes mirrored patterns found in the respective primate brains. Human gut microbes enhanced glucose production and utilization in the mouse brains, suggesting that differences in gut microbiota across species can impact brain metabolism, indicating that gut microbiota may help meet the energy needs of large primate brains.

Decasian et al. provided groundbreaking data showing that gut microbiome shapes brain function differences among primates. Image credit: DeCasien et al., doi: 10.1073/pnas.2426232122.

“Our research demonstrates that microbes influence traits critical for understanding evolution, especially regarding the evolution of the human brain,” stated Katie Amato, lead author and researcher at Northwestern University.

This study builds upon prior research revealing that introducing gut microbes from larger-brained primates into mice leads to enhanced metabolic energy within the host microbiome—a fundamental requirement for supporting the development and function of energetically costly large brains.

The researchers aimed to examine how gut microbes from primates of varying brain sizes affect host brain function. In a controlled laboratory setting, they transplanted gut bacteria from two large-brained primates (humans and squirrel monkeys) and a smaller-brained primate (macaque) into germ-free mice.

Within eight weeks, mice with gut microbes from smaller-brained primates exhibited distinct brain function compared to those with microbes from larger-brained primates.

Results indicated that mice hosting larger-brained microbes demonstrated increased expression of genes linked to energy production and synaptic plasticity, vital for the brain’s learning processes. Conversely, gene expression associated with these processes was diminished in mice hosting smaller-brained primate microbes.

“Interestingly, we compared our findings from mouse brains with actual macaque and human brain data, and, to our surprise, many of the gene expression patterns were remarkably similar,” Dr. Amato remarked.

“This means we could alter the mouse brain to resemble that of the primate from which the microbial sample was derived.”

Another notable discovery was the identification of gene expression patterns associated with ADHD, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and autism in mice with gut microbes from smaller-brained primates.

Although previous research has suggested correlations between conditions like autism and gut microbiome composition, definitive evidence linking microbiota to these conditions has been lacking.

“Our study further supports the idea that microbes may play a role in these disorders, emphasizing that the gut microbiome influences brain function during developmental stages,” Dr. Amato explained.

“We can speculate that exposure to ‘harmful’ microorganisms could alter human brain development, possibly leading to the onset of these disorders. Essentially, if critical human microorganisms are absent in early stages, functional brain changes may occur, increasing the risk of disorder manifestations.”

These groundbreaking findings will be published in today’s Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

_____

Alex R. Decassian et al. 2026. Primate gut microbiota induces evolutionarily significant changes in neurodevelopment in mice. PNAS 123(2): e2426232122; doi: 10.1073/pnas.2426232122

Source: www.sci.news