If temperature-tracking sponges can be trusted, climate change is happening much faster than scientists estimate.

A new study that used marine organisms called hard sponges to measure global average temperatures suggests that the world has already warmed by about 1.7 degrees Celsius over the past 300 years. This is at least 0.5 degrees Celsius higher than the scientific consensus stated in the UN report.

The findings, published Monday in the journal Nature Climate Change, are surprising, but some scientists believe the study authors’ conclusions give more inferences about global temperatures than can be confidently gleaned from sponges. They claim that they are doing too much.

However, this study raises important questions. How much warmer did the world get when humans were less systematically measuring temperatures around the world, even as fossil fuel-powered machines were running hard? Scientists say this is an important question. It is a problem that needs to be better understood.

The study’s authors say that industrialization before 1900 had a greater impact than scientists previously realized, and that influence is captured in centuries-old sponge skeletons and that we The standards we have been using to talk about the politics of climate change have been wrong.

“Essentially, these studies show that the industrial age of warming started earlier than we thought, in the 1860s,” said the study’s lead author, a researcher at the University of Western Australia’s Global Professor of Chemistry Malcolm McCulloch spoke about sponges. “The big picture is that the global warming clock has been moved forward by at least 10 years to reduce emissions to minimize the risks of a dangerous climate.”

Scientists not involved in the study say their colleagues are grappling with how much warming occurred in the decades after the industrial revolution and before temperature records became more reliable. .

“This is not the only effort to reexamine what we call the pre-industrial baseline and suggest we may have missed the increase in warming during the 19th century,” said Brown University paleoclimate and oceanography expert. said Kim Cobb, author of the report. Brown Institute for the Environment and Society. “This is an important area of uncertainty.”

In its latest assessment of global warming, the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimated that the Earth’s surface temperature has increased by up to 1.2 degrees Celsius since before the industrial revolution.

Some scientists believe that the IPCC process (which requires consensus) will yield conservative results. For example, scientists who study Earth’s ice have expressed concern that the Earth is approaching the tipping point of the ice sheet sooner than expected and that the IPCC’s sea level rise projections are too low.

Cobb, who did not contribute to the Nature Climate Change study, said a large amount of evidence would be needed to change what scientists call the pre-industrial baseline, but other researchers have argued that warming has increased since before the 1900s. He also said that he has found some signs that the system is not being properly accounted for. .

“How big this extra warming increase actually is is currently unknown. Is this important to study? We could be missing a tenth of a degree. Is there a? Yes, I think it’s been uncovered in a series of studies over the last six to 10 years,” Cobb said.

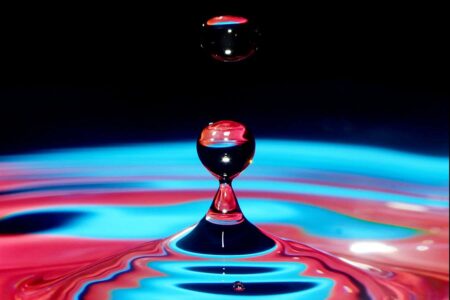

Scleros sponges are one of many climate proxies used by scientists to gather information about past climate conditions. In the dural cavernosa, the skeletal growth layers serve a similar purpose to marine biologists, just as tree rings serve a purpose to those working in the forest.

Dural sponges grow slowly, and as they grow, the chemical composition of their skeleton changes based on the surrounding temperature. This means that scientists can track temperature by looking at the ratio of strontium to calcium as an organism steadily grows.

Studies show that every half millimeter of growth is equivalent to about two years of temperature data. Living things can grow and add layers to their skeletons over hundreds of years.

“These are truly unique specimens. The reason we are able to obtain this unique data is because of the special relationship these animals have with their surrounding environment,” McCulloch said.

The study’s authors collected sponges from waters at least 100 feet deep off the coast of Puerto Rico and near St. Croix, analyzed the chemical composition of their skeletons, graphed the results, and used the data from 1964 to When compared with sea surface temperature measurements in 2012, the trends were almost identical.

Cancellous bone data dates back to 1700, predating reliable human records. This gives scientists a longer reference point to assess what temperatures were like before fossil fuels became widespread. Researchers believe this dataset is superior to other datasets calculated using her 19th century temperature measurements from ocean-going ships.

Sponge data shows that temperatures started rising in the 1860s, before the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change considered it.

But some outside researchers say the study may have made too much use of one type of proxy indicator, especially when the data is tied to only one location on Earth.

“We should be cautious in assuming that estimates from parts of the Atlantic Ocean always reflect global averages,” Gavin Schmidt, director of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, said in an emailed statement. He added that the author’s claims are probably wrong. “It’s gone too far.”

The study authors said they believe the waters off Puerto Rico have remained relatively stable, reflecting global changes similar to those elsewhere in the world.

The results suggest that humanity has already surpassed political guardrails, such as world leaders’ goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

Cobb said further work would need to be done with a dural sponge to ensure the work was accurate. And regardless of how much we are already pushing up the planet’s temperature, humanity must put the brakes on greenhouse gas production.

“Every time we get warmer, the climate impacts increase and the climate impacts worsen,” Cobb said. “We’re already living with an unsafe warming climate. … Jobs haven’t changed.”

Source: www.nbcnews.com