The culture that built Stonehenge suffered a mysterious population decline

Wirestock/Alamy

The European Neolithic culture that produced megaliths like Stonehenge experienced a major decline about 5,400 years ago, and the best evidence now is that this was due to plague.

Sequencing of ancient DNA from 108 people living in northern Europe at the time revealed that the plague bacillus Plague Yersinia pestis The condition was present in 18 of those who died.

“We think the plague killed them.” Frederick Siersholm At the University of Copenhagen, Denmark.

About 5,400 years ago, The population of Europe has declined sharplyWhy this happens, especially in the northern regions, has long been a mystery.

Ancient DNA studies over the past decade have revealed that local populations never fully recovered from the Neolithic decline, but were largely replaced by other peoples who migrated from the Eurasian steppes: in Britain, for example, by about 4,000 years ago, less than 10% of the population descended from the people who built Stonehenge.

Studies of ancient people have also uncovered some instances of the presence of the plague bacterium, suggesting an explanation that the plague may have wiped out the population of Europe, allowing steppe peoples to migrate with little resistance.

But not everyone agreed, arguing that occasional sporadic outbreaks were to be expected and not evidence of a major pandemic. Ben Krauss Keora The findings were published in 2021 at Kiel University in Germany. Plague Yersinia pestis He and his colleagues write that their DNA shows that the virus cannot survive in fleas, making it unlikely to cause a pandemic: Bubonic plague, which killed people in the Black Death during the Middle Ages, is often transmitted by the bite of an infected flea.

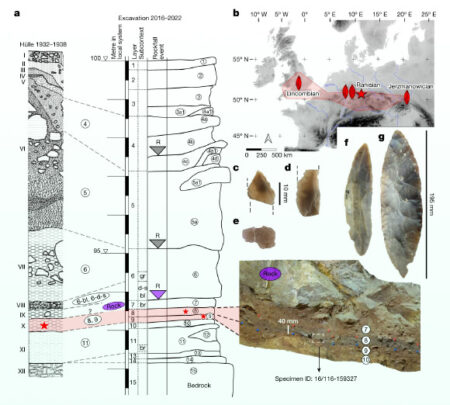

So Sirsholm and his colleagues set out to find more evidence of the plague pandemic. The 108 people whose DNA his team sequenced were buried in nine graves in Sweden and Denmark. Most of them died between 5,200 and 4,900 years ago, and they spanned several generations of four families.

Over the course of just a few generations, the plague appears to have spread three separate times, the last of which may have been caused by a genetically modified strain that was far more deadly.

“This virus is present in many people,” Searsholm said, “and it's all the same version. That's exactly what you expect when something spreads quickly.”

Plague DNA was found primarily in teeth, indicating that the bacteria entered the bloodstream and caused severe illness and possibly death, he said. In some cases, close relatives were infected, suggesting person-to-person transmission.

The research team suggests that this may be a result of: Plague Yersinia pestis It is a type of disease called pneumonic plague, which infects the lungs and spreads through droplets. Human lice can cause bubonic plagueNot only fleas but also the plague bacteria can be spread this way.

“Of course, it's worth noting that all of these people were properly buried,” says Searsholm, meaning society had not collapsed at this point. “If there really was an epidemic, we're only just seeing the beginning.”

The megalithic tomb appears to have been abandoned for several centuries after about 4900 years ago, but the 10 sequenced individuals were buried much later, mostly between 4100 and 3000 years ago. These individuals were from the steppe region and are unrelated to the people who built the tomb.

“It's a 100 percent complete turnover,” says Searsholm, “5,000 years ago, these Neolithic people disappeared, and now we have evidence that plague was rampant and widespread at exactly the same time.”

While the researchers don't claim their findings are conclusive, Searsholm says they do support the argument that plague caused the Neolithic decline.

“It's pretty clear that this virus can infect humans and can, for example, kill an entire family.”

Klaus Kiora acknowledges that the discovery shows that the plague was widespread in this particular place and time: “Previous explanations need to be somewhat revised and we can't just talk about isolated cases,” he says.

But there's no evidence of high prevalence in other areas, he says, and he thinks normal burials indicate there were no deadly epidemics. Yersinia The infection was like a long-term chronic disease.”

Sirsholm and his team plan to search for more evidence across Europe in the coming days, but the only way to know for sure how deadly the engineered strain was would be to resurrect it, which he says is far too risky to attempt.

“I think this paper will convince many of our colleagues who have been skeptical of our previous work,” he said. Nicholas Raskovin In 2018, a team of researchers from the Pasteur Institute in Paris discovered the plague bacillus in two Neolithic individuals and proposed that the decline of the Neolithic period was due to the plague.

topic:

- Archaeology/

- Infection

Source: www.newscientist.com