A treasure trove of ancient plant remains unearthed in Kenya helps explain the history of plant cultivation in equatorial East Africa, a region long thought to be important for early agriculture but where little evidence from actual crops had been found. New Research Released on July 10, 2024 Proceedings of the Royal Society BArchaeologists from Washington University in St. Louis and the University of Pittsburgh and their colleagues report the largest and most extensively dated archaeological record ever found in the East African interior.

Kakapel Rockshelter, located at the foot of Mount Elgon near the Kenya-Uganda border, is where Dr. Muller and his collaborators discovered the oldest evidence of plant cultivation in East Africa. Image by Steven Goldstein.

Until now, scientists have had little success collecting ancient plant remains from East Africa, and as a result, little is known about where and how early plant cultivation began in the vast and diverse region that comprises Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda.

“There are a lot of stories about how agriculture began in East Africa, but not much direct evidence of the plants themselves,” said archaeologist Dr Natalie Muller of Washington University in St Louis.

The work was carried out at Kakapel Rockshelter in the Lake Victoria region of Kenya.

“We found a huge array of plant life, including large amounts of crop remains,” Dr Muller said. “The past shows a rich history of diverse and flexible agricultural systems in the region, in contrast to modern stereotypes about Africa.”

New research reveals a pattern of gradual adoption of different crops originating from different parts of Africa.

In particular, cowpea remains discovered at Kakapel Rockshelter and directly dated to 2,300 years ago provide the oldest record of a cultivated crop, and possibly an agricultural lifestyle, in East Africa.

The study authors estimate that cowpea is native to West Africa and arrived in the Lake Victoria basin at the same time as the spread of Bantu-speaking peoples migrating from Central Africa.

“The discoveries at Kakapelle reveal the earliest evidence of crop cultivation in East Africa and reflect dynamic interactions between local nomadic pastoralists and migrant Bantu-speaking farmers,” said Emmanuel Ndiema of the National Museums of Kenya, a partner in the project.

“This study demonstrates the National Museums of Kenya's commitment to uncovering the deep historical roots of Kenya's agricultural heritage and to improving our understanding of how past human adaptations impact future food security and environmental sustainability.”

An ever-changing landscape

Located at the foot of Mount Elgon north of Lake Victoria near the Kenya-Uganda border, Kakapelu is a renowned rock art site containing archaeological remains reflecting more than 9,000 years of human occupation in the area. The site has been recognised as a Kenyan national monument since 2004.

“Kakapel Rockshelter is one of the few sites in the region that shows occupation by so many diverse communities over such a long period of time,” said Dr. Steven T. Goldstein, an anthropological archaeologist at the University of Pittsburgh and the other lead author of the study.

“Using innovative excavation techniques, we were able to uniquely detect the arrival of domesticated plants and animals in Kenya and study the impacts of these introductions on the local environment, human technologies and socio-cultural systems.”

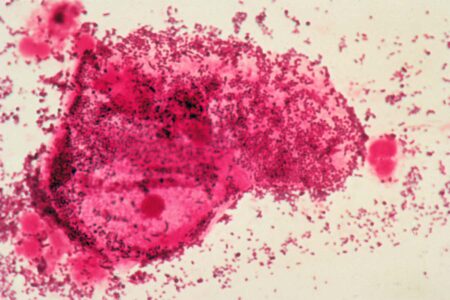

Dr Muller used flotation to separate remains of wild and cultivated plant species from ash and other debris in the furnaces excavated at Kakapelle. He has used this technique in research in many other parts of the world, but it can be difficult to use in water-scarce areas and so is not widely used in East Africa.

Using direct radiocarbon dating of charred seeds, scientists documented that cowpea (also known as black-eyed pea, today an important legume worldwide) arrived about 2,300 years ago, about the same time that people in the region began using domesticated cattle.

They found evidence that sorghum arrived from the Northeast at least 1,000 years ago.

They also found hundreds of finger millet seeds dating back at least 1,000 years.

The crop is native to East Africa and is an important traditional crop for the communities currently living near Kakapelle.

One of the unusual crops that Dr. Muller found was a burnt but completely intact pea plant (Pisum), which is not thought to have been part of early agriculture in this region.

“To our knowledge, this is the only evidence for peas in Iron Age East Africa,” Dr Muller said.

This particular pea has been featured in the newspaper and presents a little mystery in itself.

“The standard pea that we eat in North America was domesticated in the Near East,” Dr Muller said.

“It is thought that it was cultivated in Egypt and then travelled down the Nile via Sudan to reach East Africa – which is probably how sorghum got to East Africa. But there is another type of pea called the Abyssinian pea that was cultivated uniquely in Ethiopia, and our sample could be either.”

Many of the plant remains that Dr. Muller and his team found at Kakapelle could not be positively identified because even modern scientists currently working in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda do not have access to a proper reference collection of East African plant samples.

“Our study shows that agriculture in Africa has been constantly changing as people migrate, introduce new crops and abandon others at the local level,” Dr Muller said.

_____

Muller others2024. Proceedings of the Royal Society Bin press; doi: 10.1098/rspb.2023.2747

This article is a version of a press release provided by Washington University in St. Louis.

Source: www.sci.news