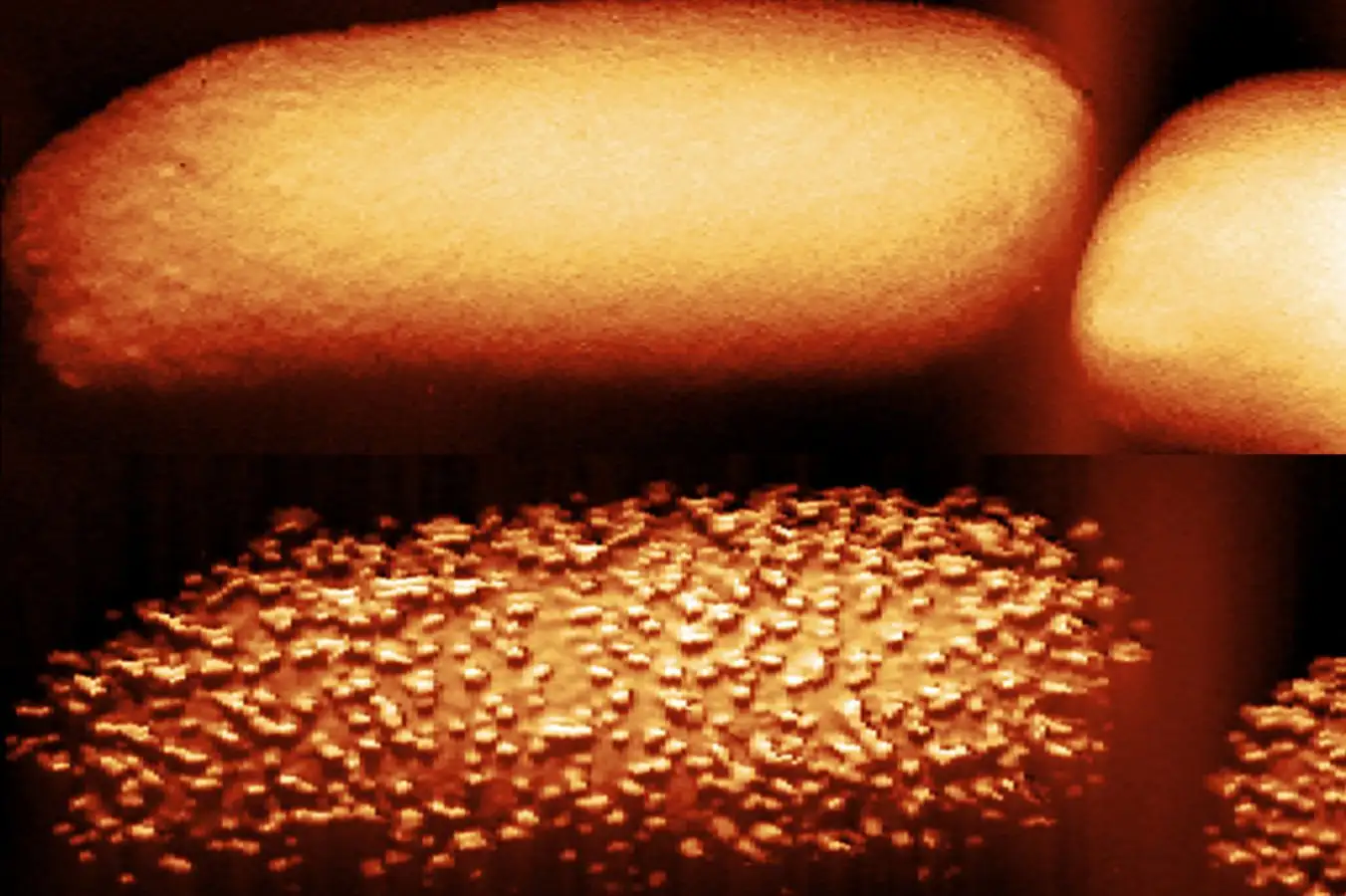

The above image displays untreated E. coli bacteria, with the lower image showing the effects of polymyxin B after 90 minutes.

Carolina Borrelli, Edward Douglas et al./Nature Microbiology

High-resolution microscopy unveils how polymyxins, a class of antibiotics, penetrate bacterial defenses, offering insights for developing treatments against drug-resistant infections.

Polymyxins serve as a last-resort option for treating Gram-negative bacteria responsible for serious infections like pneumonia, meningitis, and typhoid fever. “The priority pathogens identified by the top three health agencies globally are predominantly Gram-negative bacteria, highlighting their complex cell envelopes,” states Andrew Edwards from Imperial College London.

These bacteria possess an outer layer of lipopolysaccharides that functions as armor. While it was known that polymyxins target this layer, the mechanisms of their action and the reasons for inconsistent effectiveness remained unclear.

In a pivotal study, Edwards and his team employed biochemical experiments combined with nuclear power microscopy, capturing details at the nanoscale. They discovered that polymyxin B, amongst other treatments, actively targets E. coli cells.

Shortly after treatment commenced, the bacteria rapidly began releasing lipopolysaccharides.

Researchers observed that the presence of antibiotics prompted bacteria to attempt to assimilate more lipopolysaccharide “bricks” into their protective walls. However, this effort resulted in gaps, allowing antibiotics to penetrate and destroy the bacteria.

“Antibiotics are likened to tools that aid in the removal of these ‘bricks’,” Edwards explains. “While the outer membrane doesn’t entirely collapse, gaps appear, providing an entryway for antibiotics to access the internal membrane.”

The findings also elucidate why antibiotics occasionally fail: they predominantly affect active, growing bacteria. When in a dormant state, polymyxin B becomes ineffective as these bacteria do not produce armor strong enough to withstand environmental pressures.

E. coli images exposed to polymyxin B illustrate changes to the outer membrane over time: untreated, 15 mins, 30 mins, 60 mins, and 90 mins.

Carolina Borrelli, Edward Douglas et al./Nature Microbiology

Interestingly, researchers found that introducing sugar to E. coli could awaken dormant cells, prompting armor production to resume within 15 minutes, leading to cell destruction. This phenomenon is thought to be applicable to other polymyxins, such as polymyxin E, used therapeutically.

Edwards proposes that targeting dormant bacteria with sugar might be feasible, though it poses the risk of hastening their growth. “We don’t want bacteria at infection sites rapidly proliferating due to this stimulation,” he cautions. Instead, he advocates for the potential to combine various drugs to bypass dormancy without reactivating the bacteria.

topic:

Source: www.newscientist.com