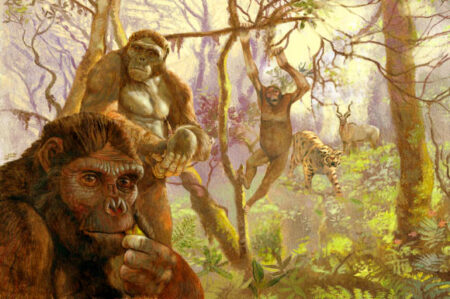

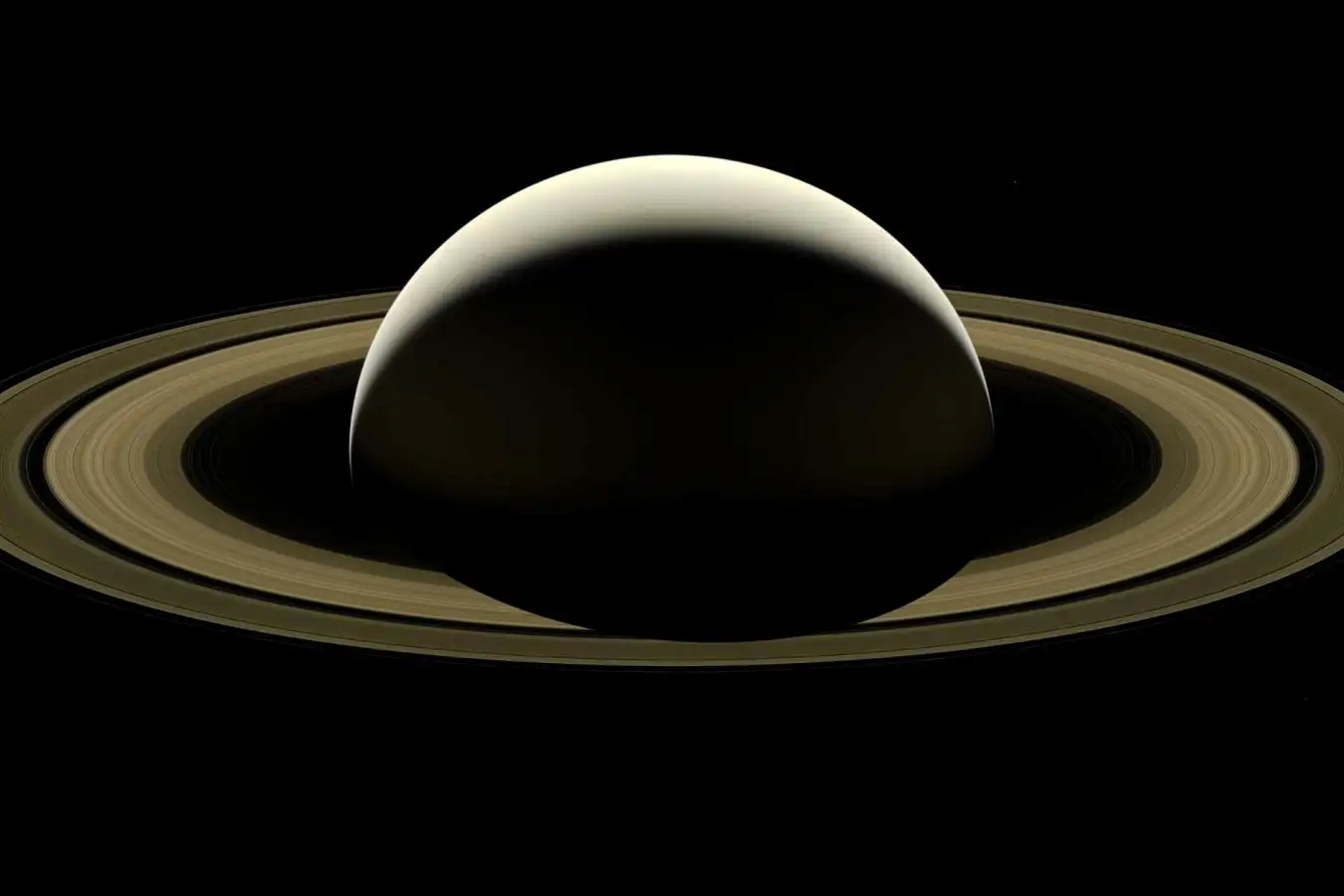

A stunning view of Saturn and its rings as seen by the Cassini spacecraft NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

New findings indicate that dust particles from Saturn’s rings are extended farther above and below the planet than previously assumed, implying that the rings might be shaped like large, dusty donuts.

The central structure of Saturn’s rings is remarkably thin, stretching out for tens of thousands of kilometers while only measuring around 10 meters in height, which gives Saturn its iconic look from Earth. However, variations exist, such as the outer E-ring that is inflated and replenished by ice ejected from Saturn’s moon Enceladus, which has an ocean beneath its surface.

In a recent study, Frank Postberg and his team at the Free University of Berlin examined data from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft, which completed 20 orbits in its final year of operation in 2017. During these orbits, the spacecraft took a steep trajectory through the rings, starting from a distance up to three times Saturn’s radius and moving downwards towards three times Saturn’s radius.

At the height of Cassini’s orbital path, its spectrometer, known as the Cosmic Dust Analyzer, detected hundreds of tiny rock particles with a chemical makeup similar to those found in the iron-deficient main rings. “This spectral type is genuinely unique within the Saturn system,” Postberg stated.

“While more material is near the surface of the rings, it is still astonishing that these particles are found so far above and below the ring surface,” he added.

Postberg and his collaborators determined that to reach heights greater than 100,000 kilometers from the main ring, the particles must be traveling at speeds exceeding 25 kilometers per second to break free from Saturn’s gravitational and magnetic forces.

Postberg noted that the exact mechanism achieving such speeds remains uncertain. The simplest explanation might be that a minor meteorite strikes the ring, scattering particles; however, this does not generate debris quickly enough.

New research suggests that when micrometeorites impact Saturn’s rings, they could generate sufficiently high temperatures to vaporize the rocks, implying that Saturn’s rings are older than once believed. Postberg and his team propose that this vaporized rock could exit the ring at much higher speeds than expected and then condense far from the planet.

It is surprising to find dust at such distances from the main ring. According to Frank Spahn from the University of Potsdam in Germany, who was not part of the study, this is significant because the particles in Saturn’s primary rings are small, collide rarely, and are sticky, leading to collisions that behave more like snowballs colliding than like billiard balls.

Micrometeorite impacts are prevalent throughout the solar system; hence, similar processes might be occurring on other ringed planets like Uranus. “If a ring of ice experiences a high-velocity impact, this phenomenon could be widespread; we would expect analogous dust rings above and below the other rings,” Postberg concluded.

Explore Chile’s astronomical wonders. Discover the most advanced observatory and gaze at the stars under the clearest skies on the planet. Topics:

Chile: The Global Center of Astronomy

Source: www.newscientist.com