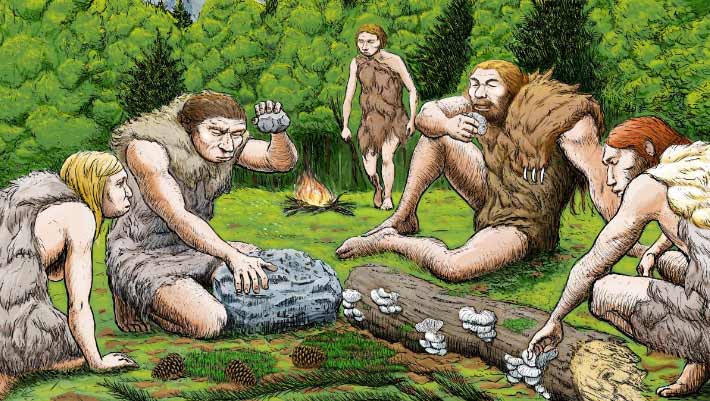

In 2015, archaeologists discovered Neanderthal fossils. Grotte Mandolin is located on the Mediterranean coast of France, in the shadow of a rock overhanging directly into the Rhône River valley. Nicknamed Thorin, the fossil is one of the most similar Neanderthal remains found in France since its discovery in Saint-Césaire in 1979. Globe Institute researcher Martin Sikora and his colleagues combined archaeological, chronostratigraphic, isotopic, and genomic analyses to reveal that Thorin belonged to a Neanderthal population that remained genetically isolated for 50,000 years. Apart from Thorin’s lineage, they found evidence of gene flow in the genome of the Les Côtés Neanderthal from another lineage that diverged from the ancestral lineage of European Neanderthals more than 80,000 years ago. The findings suggest the existence of multiple isolated Neanderthal communities in Europe close to the time of extinction and shed light on their social organization. Despite the close geographical proximity of these populations, there was limited, if any, interaction between the different Neanderthal populations during the last millennium.

Neanderthal. Image courtesy of Abel Grau, CSIC Communication.

“When we look at the Neanderthal genome, we see that they were quite inbred and didn’t have a lot of genetic diversity,” Dr Sikora said.

“They’ve lived in small groups for generations.”

“Inbreeding is known to reduce the genetic diversity of populations, which if continued over long periods of time can have negative effects on the viability of the population.”

“The newly discovered Neanderthal genome is from a different lineage to other late Neanderthals studied so far.”

“This supports the idea that Neanderthal social organization was different from that of early modern humans, who appear to have been more connected.”

“In other words, compared to Neanderthals, early modern humans were more likely to connect with other groups, which was advantageous for their survival.”

“This is purely speculation, but the concept of being able to communicate more and exchange knowledge is something humans can do that Neanderthals, who were organized in small groups and lived isolated lives, may not have been able to do to some extent.”

“And that’s an important skill,” noted Dr Tarshika Vimala, a population geneticist at the University of Copenhagen.

“We see evidence that early modern humans in Siberia, living in small communities, formed so-called mating networks to avoid problems with inbreeding, something that wasn’t seen in Neanderthals.”

Thorin’s fossils were first discovered in Mandolin Cave in 2015. Mandolin Cave is a cave that is thought to have been the site of an early Homo sapiens But not at the same time, and he is still being slowly unearthed.

Based on Thorin’s location in the cave deposits, archaeologists have speculated that he may have lived approximately 45,000 to 40,000 years ago.

To determine his age and relationships to other Neanderthals, the team extracted DNA from his teeth and jaw and compared his entire genome sequence to previously sequenced Neanderthal genomes.

Surprisingly, initial genome analysis suggested that Thorin’s genome was very different from other late Neanderthals and very similar to the genomes of Neanderthals who lived more than 100,000 years ago, suggesting that Thorin is much older than archaeological estimates.

To solve the mystery, the researchers analyzed isotopes from Thorin’s bones and teeth to gain insight into the type of climate he lived in. Late Neanderthals lived during the Ice Age, while early Neanderthals enjoyed a much warmer climate.

Isotopic analysis showed that Thorin lived in a very cold climate and was identified as a late Neanderthal.

Compared to previously sequenced Neanderthal genomes, Thorin’s genome is most similar to the individual from Gibraltar, leading the authors to speculate that Thorin’s population may have migrated from Gibraltar to France.

“This means that a previously unknown Neanderthal population was present in the Mediterranean, stretching from the westernmost tip of Europe to the Rhône Valley in France,” said Dr Ludovic Slimac, researcher at Toulouse-Paul Sabatier University and CNRS.

Knowing that Neanderthal communities were small and isolated may hold the key to understanding their extinction, because isolation is generally thought to be detrimental to a population’s fitness.

“It’s always a good thing for one group to have contact with another,” Dr Vimala said.

“Prolonged isolation limits genetic diversity and reduces the ability to adapt to changes in climate and pathogens. It’s also socially limiting, as they don’t share knowledge or evolve as a group.”

But to truly understand how Neanderthal populations were structured and why they became extinct, researchers say many more Neanderthal genomes need to be sequenced.

“If we had had more genomes from other regions over the same time period, we probably would have found other deeply structured populations,” Dr Sikora said.

A paper on the results of this study was published today. journal Cell Genomics.

_____

Ludovic Slimak others2024. The long genetic and social isolation of Neanderthals before their extinction. Cell Genomics 4(9):100593;doi: 10.1016/j.xgen.2024.100593

Source: www.sci.news