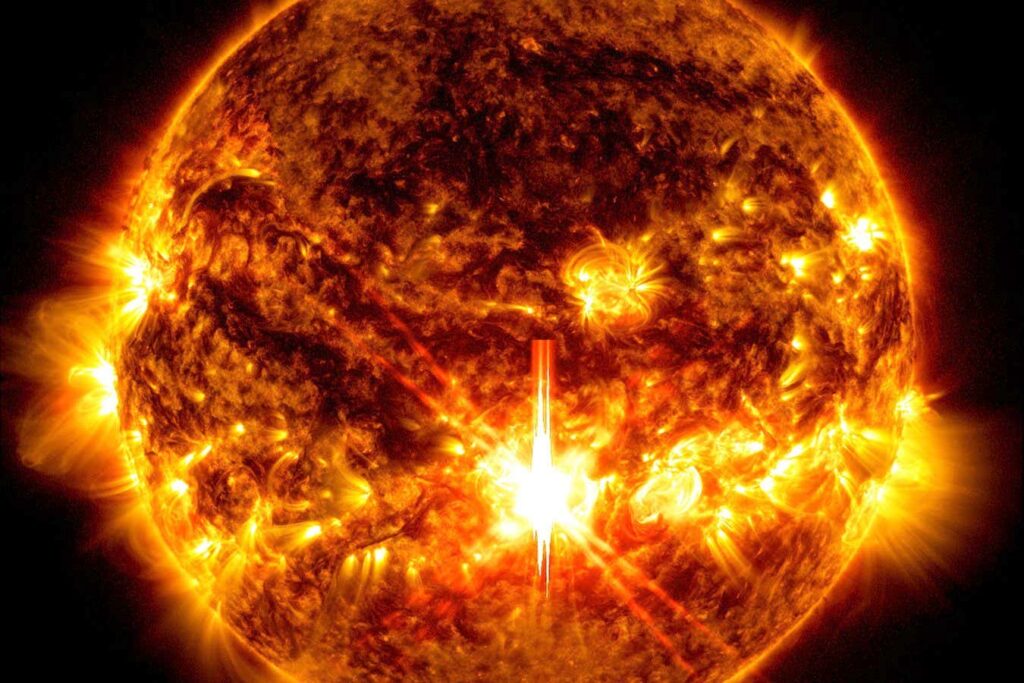

This relatively small solar flare that occurred in October (a bright flash at the center discovered by NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory) would be dwarfed by a superflare.

NASA/SDO

The sun can produce extremely powerful bursts of radiation more often than we think. According to research on stars similar to the Sun, such “superflares” appear to occur about once every 100 years, and are particle storms that can have a devastating effect on electronic equipment on Earth. may be accompanied by The last major solar storm to hit Earth was 165 years ago, so we may be hit by another solar storm soon, but how similar is our Sun to these other stars? is unknown.

Direct measurements of solar activity did not begin until the mid-20th century. In 1859, our star produced a very powerful solar flare, or emission of light. These are often associated with subsequent coronal mass ejections (CMEs), bubbles of magnetized plasma particles that shoot into space.

In fact, this flare was followed by a CME that crashed into the Earth, causing a violent geomagnetic storm. This was recorded by astronomers at the time and is now known as the Carrington phenomenon. If this were to happen today, communications systems and power grids could be disrupted.

There is also evidence that there were even more powerful storms on Earth long before the Carrington incident. Assessment of radiocarbon content in tree rings and ice cores suggests that extremely high-energy particles occasionally rained down on Earth over several days, but this could be attributed to a one-time, massive solar outburst. It is unclear whether this is the case or whether it is due to several solar explosions. something small. It’s also unclear whether the Sun can produce such large flares and particle storms in a single explosion.

The frequency of these signs on Earth, and the frequency of superflares that astronomers have recorded on other stars, suggests that these giant bursts tend to occur hundreds to thousands of years apart. .

now, Ilya Usoskin Researchers from the University of Oulu in Finland studied 56,450 stars and found that stars similar to the Sun appear to emit superflares much more frequently.

“Superflares in stars like the Sun occur much more frequently than previously thought, about once every century or two,” Usoskin said. “If we believe this prediction for the Sun is correct, we would expect the Sun to have a superflare about every 100 to 200 years, and the only extreme solar storms we know of occur about once every 1500 or 2000 years. There will be a mismatch.”

Using the Kepler Space Telescope to measure the brightness of stars, Usoskin and colleagues detected a total of 2,889 superflares in 2,527 stars. The energies of these flares were 100 to 10,000 times the size of the Carrington event, the largest flare measured from the Sun.

Usoskin said it remains to be seen whether such large flares also cause large-particle phenomena, such as there is evidence for on Earth, but current solar theory cannot explain such large flares. That’s what it means. “This raises questions about what we’re actually seeing,” he says.

“It’s very impressive for a stellar flare survey,” he says. Matthew Owens At the University of Reading, UK. “They’ve clearly developed a new way to detect flares with increased sensitivity.”

Owens says it’s even harder to determine how much this tells us about the Sun’s flaring activity, in part because it’s difficult to accurately measure the rotation rates of other stars. It is said that it is for the sake of “The devil is in the details,” he says.

“The rotation rate is important because it is related to how the star generates its magnetic field, and magnetic fields are related to flare activity,” Owens said.

topic:

Source: www.newscientist.com